Expressive art born of 17th-century seclusion

Updated: 2012-12-07 12:56

By Kelly Chung Dawson in New York (China Daily)

|

||||||||

The recluse is well established in Chinese art, an enduring symbol of self-sufficiency. He is immortalized as the lone scholar surrounded by scrolls, the fisherman with craggy cliffs as his witness.

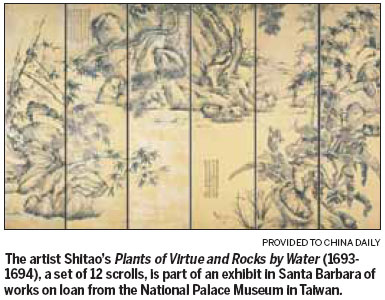

A new exhibition at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art in Southern California gives voice to those who withdrew from Chinese society in pursuit of the reclusive ideal - both before and after political upheaval made solitude a key to survival.

The Artful Recluse: Painting, Poetry and Politics in Seventeenth-Century China features nearly 60 paintings, scrolls, fans and poems from a period that featured the dramatic fall of the Ming Dynasty (around 1644) and the tumultuous rise - later dubbed the Chaos - of the Qing Manchu.

The show draws on work from the National Palace Museum in Taiwan, six private collections from the US and Taiwan, and five public institutions. The Artful Recluse will also be exhibited at the Asia Society in New York next year.

In the decades before the fall of the Ming, the imperial court was in flux. Corruption, political intrigue and uncertainty inspired prominent scholar-officials such as Shitao and Bada Shanren to withdraw from public life in search of rural solitude. Trained in philosophy, art and literature, they retreated to mountain dwellings and became immersed in calligraphy, poetry, painting and the study of the masters.

The output of these elite hermits would make the 17th century one of the greatest periods for Chinese art.

Their bucolic disengagement was a form of silent protest that became even more meaningful after the dynasty's demise, said Susan Tai, curator of Asian art at the Santa Barbara museum.

"This idea of reclusion was not new in Chinese art," she told China Daily. "This is deeply rooted in Chinese culture. Then later, when many of these men were in hiding as a result of their association with the Ming, their art reflected a sense of loss, frustration, despair and, ultimately, a sense of resolve.

"This art is about freedom and escape; it permeates the paintings."

Although their media varied, the artist-recluses of the period were singularly concerned with their natural surroundings, Tai said.

"For Chinese, reclusion means a retreat to nature," she explained. "In Taoism, Buddhism and even Confucianism, you're taught that nature is where you find comfort - it's where your problems are resolved."

Voluntary seclusion was, ironically, a springboard for artistic engagement, said Peter Sturman, professor of art history and architecture at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and co-curator of the exhibition.

"The more we looked at this subject, the more we realized it was something vital to the time. For frustrated intellectuals, reclusion gave people a way to express their wish to get away from something and live this pure existence.

"There was a certain rhetoric of reclusion, in which very famous people prominently declared a desire to be recluses. And later, when thousands and thousands of people remained loyal to the Ming Dynasty and couldn't face the prospect of being under alien rule, reclusion became a real and necessary aspect of many people's lives. Some people committed suicide; some became Buddhist monks; many others disappeared into the hills."

The West has often misunderstood this core Chinese concept, Sturman believes.

"It's important to think of reclusion as an actual practice, but to also understand that they weren't really recluses," he said. "They were active and social. These paintings are not entirely about creating walls or barriers. It was a private discourse, but they were looking for others to share their disengagement."

In the exhibition's catalog, he writes: "For the artist, reclusion represented a private space, a chamber within the mind, but it was a private space that was always intended to be shared. The goal of this exhibition is to enter those private spaces and explore the graphic and textual structures with which each artist conceived his or her place in a dynamically changing world."

Painters such as Chen Jiru (1558-1639) and Dong Qichang (1555-1638) devoted time to the development of Chinese art theory, in the form of essays and debate with fellow scholars. Dong pushed an ideal in which painters should build on the work of masters, honing an individual style with less emphasis on imitation.

The paintings often reference art that has come before, Tai said.

"Chinese painters have traditionally always been humble to history, because they accept that the great masters have already done everything. But they took delight in picking and choosing from the vocabulary of the past masters, to convey their own feelings about nature and society.

"Our hope is for people to realize how diverse the Chinese landscape can be in the hands of different people."

Many will be surprised by the individuality expressed in the paintings, Sturman said.

"Your average American's view of China is skewed," he said. "It's hard for most Westerners to recognize that personal expression is something intrinsic to Chinese painting and poetry and literature and art. It has been for thousands of years.

"What you find in these paintings is the outlet, a way for people to express themselves as individuals."

kdawson@chinadailyusa.com

Relief reaches isolated village

Relief reaches isolated village

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Earth Day marked around the world

Earth Day marked around the world

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Health new priority for quake zone

Xi meets US top military officer

Japan's boats driven out of Diaoyu

China mulls online shopping legislation

Bird flu death toll rises to 22

Putin appoints new ambassador to China

Japanese ships blocked from Diaoyu Islands

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

US Weekly

|

|