No child's play raising children of parents working overseas

Updated: 2012-12-26 07:14

By He Na and Hu Meidong (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

Huang Jie is one of the children left behind in Fujian province by parents who work abroad. Cui Meng / China Daily |

|

Olsen sits with his aunt in front of the computer. At 11 am every day, he has a video chat with his parents in the United States. Photos by Cui Meng / China Daily |

|

Above and below: Children at Guantou Overseas Chinese Kindergarten. They all hold foreign passports. |

Hunt for better economic opportunities takes its toll on families, report He Na and Hu Meidong in Fujian province.

Wearing a small bib patched with different-colored pieces of cloth, his cheeks roughened by long exposure to the cold winter weather, 17-month-old Huang Jie from Guanqi village, Guantou township, Fujian province, appears no different from any of the other local children.

Despite his young age, he spares no effort to move a chair taller than himself from one room to another, repeating the deed several times a day.

Fearing he may hurt himself, his grandmother, 48-year-old Liu Huizhen, sometimes bends at the waist and with outstretched arms follows the little boy's steps. The scene is repeated many times every day.

"Olsen! Stop and take a rest!" shout the passing villagers, who can see the boy through the open doorway. Whenever he hears the word "Olsen", the boy stops and raises his head in the direction of the sound before resuming his "work".

"Olsen" is what the local people like to call the boy, and after hearing it so many times he has already managed to make the connection between the name and himself. However, when people call him Huang Jie, he makes no response.

Giving their children English names is fashionable among young couples in China's larger cities, but Olsen's grandparents are farmers, and their knowledge of social fashion is limited. However, their daughter has told them to call the boy Olsen, because it's the name on his passport.

Olsen Huang was born in New York in July, 2011. His parents are both busy working they don't have time to look after him, so his grandparents took him in when he was sent to the village aged just 100 days.

There are many small foreigners living there, according to the village head Li Xiaoming - and he should know, his 1-year-old nephew, Li Youwen, is one of them.

"He's my brother's son. My brother went to the United States five years ago. The boy was born in New York, but my brother works at a restaurant in a southern state," said Li Xiaoming. "The boy was sent to Guantou when he was eight months old. For the past four months, he has cried heavily at night and we know he's looking for his mom."

Large-scale emigration

Currently, more than 2,000 overseas-born children, known in China as "left-behind" kids, live with grandparents or relatives in Guantou.

"Almost every family here has some one working overseas. Although their footsteps cover more than 30 countries, most have gone to the US, Canada and Japan," said Lin Xiuzhu, president of Guantou Overseas Chinese Kindergarten, the largest in the town, where more than 90 percent of the students are foreign nationals.

"When I opened the kindergarten in 2005, there were only 80 foreign-born kids, but the number has increased sharply year by year. We have nine classes now and the number of kids has soared to 380. To guarantee quality of tuition, we no longer recruit children younger than 3," she said.

Other regions in Fujian, such as Mawei district in Fuzhou, Fuqing city, Changle city and Luoyuan county are also playing host to kids born to Chinese parents overseas.

Around 20,000 children with US nationality live in Fuzhou, said Zheng Qi, president of the Fukien Benevolent Association of America, quoted in the Fuzhou Evening News. If you include those holding other nationalities, the number could be as high as 60,000, he said.

Guangdong province and a number of other costal regions are experiencing the same thing. Enping in Guangdong has acquired the nickname "Little United Nations" because of the number of children born overseas.

Large-scale emigration means that the population of Guantou is mainly composed of elders and children. Most young people in the town hail from Sichuan province.

"Because most Chinese living overseas do manual work, in restaurants and suchlike, or run their own small businesses, the heavy workload makes the task of taking care of small children impossible, irrespective of whether they have been granted foreign nationality," said Lin Xiuzhu.

In addition, many countries have strict child-care regulations. If parents are perceived to be failing their kids and are reported, they run the risk of having their children taken into care. Some parents could even be imprisoned.

Many young couples see no alternative but to send their kids back to their parents when they are only a few months old. The kids are often taken abroad again aged 4 or 5 to attend elementary school.

"Although we have plenty of students, we see kids leave and go abroad every month. Kids generally leave China aged 5, because their US passports are only valid for five years. However, when they arrive here they are at a good age to learn a new language; the earlier they come here, the easier it is for them to integrate," according to Lin Xiuzhu.

Onscreen parents

Lin Dandan, Olsen's mother, saw him off at the airport last year. However, the boy was too young to remember that his mom was the one crying like a baby.

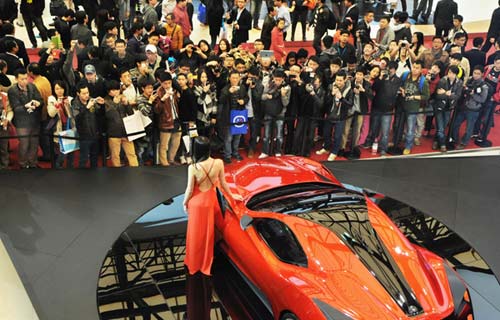

Since then, at 11 am every day, Liu Huizhen, Olsen's grandmother, ensures he is sitting in front of the computer, ready for a video chat with his mother when she gets home after her day's work.

"We have a video chat almost every day. Seeing Olsen's cute face and the little changes as he grows is the best time in my day," said Lin Dandan.

Although Olsen's grandmother has told him repeatedly that the two people in the computer are his mom and dad, the length of their separation means the little boy has little interest in the people waving to him on the screen and trying to attract his attention.

However, practice makes perfect, and with lots of practice the penny seems to have finally dropped. Even though Olsen still doesn't fully understand, he always points at the computer when people ask him where his parents are.

Most of those who went overseas years ago now have a foreign nationality, but more recent arrivals still have a long wait ahead of them.

Huang Hui, Olsen's father, went to the US in 2002 and now works as a chef in New York. He was granted US nationality last year, but Lin Dandan, who joined her husband in 2008 and works as a waitress, is still waiting. She works more than 10 hours a day and earns $2,500 a month.

She's pregnant again, so to save money the couple lead a thrifty life, but they still provide for Olsen. In addition to sending him baby formula and diapers, they often mail clothing and toys.

"We can't be with him, so we just want to give him gifts to compensate for that," Lin Dandan said.

"My daughter hasn't been home for five years. She often cries when we are having a video chat and says it's because she misses us and Olsen. But I know she has a hard life overseas," said her mother.

'Greater care, attention'

Olsen's case is far from unique, according to Lin Rufeng, a teacher at Guantou Overseas Chinese kindergarten. Even kindergarten kids aged 4 or 5 will say "computer" when people ask about their parents.

"They have a wealthy life compared with the local kids. Some of their clothes and toys are better than those of kids living in cities, but they are short of their parents' love," she said.

The children often display a special interest in younger, rather than older, people, and have a marked attachment to teachers, compared with kids that live with their parents. They are very easily satisfied; a simple hug makes them so happy, according to the teacher.

"So, in addition to teaching, irrespective of whether we are single or married, we try to behave like mothers and show these kids greater care and more attention," she said.

Along with the extra care, classes are also designed to take the kids' situation into account.

"We don't have English classes, because many parents living abroad say it's better for the kids to learn English overseas from the very beginning. Instead, we have started classes intended to foster an ability for independent living and helping each other," said the kindergarten president Lin Xiuzhu.

"Chinese language and culture is the other major subject we put special effort into. Although the kids hold foreign nationalities, learning about Chinese culture will help them trace their roots when they grow up," she said.

"Every time kids leave, we feel sad for several days. But to help them develop, I agree with sending them back to their parents as early as possible. That's because the grandparents usually just look after the kids' health, rather than fostering good habits," she added.

Her opinion was shared by Xin Ziqiang, vice-president of the School of Social Development at the Central University of Finance and Economics.

"Grandparents are less connected with current social trends and can't form the same sort of attachments as those between children and their parents. People who lacked parental support during childhood are vulnerable. They are likely to be less confident and more introverted when they reach adulthood. Kids without parental care have fewer chances to participate in activities with their peers and that can result in poor social-communication abilities," he said.

Xiong Bingqi, deputy director of the 21st Century Education Research Institute in Beijing, also attached great importance to parental interaction. "Preschool education is really about parents educating their kids. Without the parents' involvement, this early education means nothing. Although these kids are never short of money, they are still 'left-behind', just like the kids of migrant workers. Children who don't see their parents for an extended period are naturally short of family love, and no matter how hard they try, the grandparents simply can't compensate for this," he said.

"The best way to solve the problem is to send the children back to their parents as soon as possible, but if that can't be done, the parents must arrange as many phone calls and video chats as possible so the kids know their parents' love and affection are more valuable than expensive clothes and toys," he said.

Yang Wanli and Peng Yining contributed to this story.

Contact the reporter at hena@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily 12/26/2012 page9)

Relief reaches isolated village

Relief reaches isolated village

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Earth Day marked around the world

Earth Day marked around the world

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Health new priority for quake zone

Xi meets US top military officer

Japan's boats driven out of Diaoyu

China mulls online shopping legislation

Bird flu death toll rises to 22

Putin appoints new ambassador to China

Japanese ships blocked from Diaoyu Islands

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

US Weekly

|

|