In a disaster area, work should always come first

Updated: 2013-04-25 08:12

By Tang Yue (China Daily)

|

||||||||

Knowing I am covering the earthquake in the epicenter, a lot of friends have shown deep concerns for me, and I really appreciate that.

But reporters are creatures bursting with curiosity and always eager to be at the front. For reporters, covering disasters is more like an opportunity rather than a risk.

It is hard to control your ego while you are flooded with people calling you brave and righteous. Reporters are just human beings.

But you have to control it. The worst situation would be that you become narcissistic before you arrive at the disaster area.

I have constantly been reminding myself: why am I here?

I am a reporter. I am here to cover the news. My work should always come first, and the personal experience second.

I am not saying that reporters should not share their private thoughts, as long as those feelings are meaningful for the audience.

I believe the point of our "Reporter's Log" is to give readers an opportunity to see the quake zone through our eyes. It's not meant to be a forum for boasting about how much we've suffered.

We have suffered, of course: cold weather, hunger, fatigue and danger. But am I afraid? Not at all. Not when I traveled to the epicenter, not when I was dodging falling rocks.

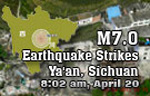

I did panic for a few seconds during an aftershock on Sunday, the second day after the magnitude-7 earthquake. It was the first time I had experienced an earthquake. The earth was shaking, and so were the buildings around me.

But I soon became numb to all the aftershocks, just like the survivors. The aftershocks kept happening, but it didn't interrupt people from going about their daily lives.

To be honest, some of my colleagues in the disaster zone have had faced more difficulties than me, not to mention the people who lost their families and homes in the tragedy. Some reporters who arrived at the area earlier than me woke up in sleeping bags soaked with rainwater.

I don't have any reason to show any self-pity, although I posted a few status updates on my social networking page. I could not help it.

But what is worse than showing off is being more of a hindrance than a help. When your heroism overpowers your professionalism, you are more of a nuisance.

There are some enthusiastic volunteers whose presence in the area has added to the difficulties that rescue workers face. In one instance, rescuers received a message from a volunteer who was lost and asked for help.

Rescuers hurried to the spot where the volunteer said he got lost, but by the time they arrived he sent another message saying he had found his way out of the mountains and didn't need their help anymore.

Another volunteer I met wearing ripped jeans said she planned to walk 10 kilometers to get to the epicenter. I didn't think she would make it.

A middle-aged man sought attention from the national media, claiming he had been here to help since the earthquake struck. He showed them a file full of newspaper clippings of his stories.

I am not saying they don't have a right to be here, to take pictures and get raw materials. But the question is: how much can you help? Are you the right person to help?

There was one guy I liked. Brother Chen, a Sichuan resident and a veteran, participated in the rescue work after a devastating flood in 1998 and the Sichuan earthquake in 2008.

He was quiet and had no interest in socializing. He was more capable than many amateur rescuers, but he chose to spend his time driving rescue crews around the area. It was a boring job compared with digging people out of the debris, but one that needed to be done.

As for reporters, our job is not easy, but we are more of a nuisance in many cases.

To cover a story about high school students going back to class, at least 30 reporters squeezed into a classroom with 110 students. They asked questions, cracked the shutters and the lights from their cameras bothered the students. The teachers eventually asked the reporters to leave.

How do you pick the right time, location and angle for a story? How do you write a story that is not a cliche? How do you spot a problem that has been ignored? How do you find a story that hasn't been told? It takes time, strength and patience. It takes ethics and talent.

In a word: professionalism. I was really worried about being a burden rather than a helper.

In the end, many thanks go to my editors and other reporters based in Beijing. We had the cool experience, while they worked long hours fixing our stories.

Every time I see my story in the newspaper, I am filled with gratitude.

Contact the writer at tangyue@chinadaily.com.cn

(China Daily 04/25/2013 page5)

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Sluggish growth takes its toll on foreign lenders

Investors find a home in overseas real estate

More Chinese travel overseas, study reveals

Xi meets former US heavyweights

Li in plea to quake rescuers

Canada to return illegal assets

Beijing vows to ease Korean tensions

Order restored after deadly terrorist ambush

US Weekly

|

|