The symbol for happiness

Updated: 2013-04-26 13:11

By Lao Huang and Xiao Chu (China Daily)

|

||||||||

From rain to morning sickness, a character to brighten almost anything

在这个娱乐爆炸的时代, 你能想象出古人听到鼓声便欣喜若狂的样子吗?

With a movie at the box office every week and with our phones and tablets bombarded with online memes by the minute, one might be forgiven for imagining that ancient peoples would have been a bit starved for entertainment, what with not having pictures of cats "can hasing cheezburgers" beamed into their palms. However, the ancient Chinese were a righteously funny bunch, able to have a laugh and a good time with something as simple as a drum.

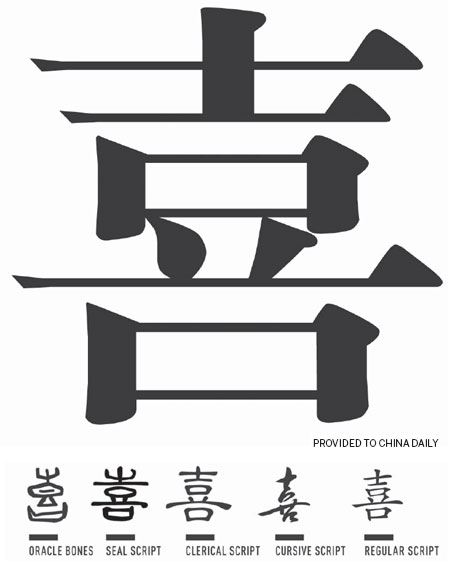

As the ultimate symbol for happiness and joy in Chinese, 喜 (xǐ) captures a delightful time in ancient human history when people were happy to be entertained by the simplest things. On top is 壴, an evolved pictographic depiction of a drum on a rack. On the bottom is 口, mouth, which indicates that the drummer's audience would sing or laugh. Either way, xi was used to describe drum beat-induced delight.

Besides music, romantic love brings joy to the world as well. Three thousands years ago, in Book of Songs (《诗经》Shījīng), a maiden in love described her feelings with the lines: "既见君子,我心则喜" (jì jiàn jūnzǐ, wǒ xīn zé xǐ), meaning: "Having seen my Prince Charming, my heart is delighted." Another usage example appears a few hundred years later during the time of the philosopher Mencius

(孟子 mèngzǐ). He once praised the quality of one of his disciples by saying: "子路,人告之以有过,则喜。" (Zǐ Lù, rén gào zhī yǐ yǒu guò, zé xǐ.), meaning: "Zi Lu (a disciple) is pleased that people point out his mistakes."

Whether it is a love poem from Classic of Poetry, the earliest anthology of Chinese poems and songs, or a weibo post by a young woman dreamily rambling about her boyfriend, time seems not to have changed the essence of xi.

Quite a few idioms used today use xi to describe the status of being overjoyed: 大喜过望 (dà xǐ guò wàng) means "be pleased beyond expectation" while 喜不自胜 (xǐ bú zì shèng) means "be transported with joy". When your heart is filled with joy, it is hard not to show it, hence the term 喜形于色 (xǐ xíng yú sè) meaning "light up with pleasure". You can use 喜怒无常 (xǐ nù wú cháng) to describe high and low mood swings, and the next time you are asked the question: "Do you want the good news or the bad news?" You will most likely have a悲喜交加 (bēi xǐ jiāo jiā) moment, meaning "mixed emotions".

Xi is a harbinger of good news, and naturally, good news is called喜讯 (xǐxùn) or "pleasing message". What about films or performances that get you giggling? For this, xi comes in the form of 喜剧 (xǐjù), meaning comedy. Stick xi in front of anything, and it will instantly turn into something joyful, even in the case of rain - 喜雨 (xǐyǔ) means "pleasing rain", which normally occurs in spring. What about air that is pleasing? It is called 喜气 (xǐqì), meaning the happy expression on people's faces or just the general atmosphere.

You might be surprised that spiders can be pleasing in Chinese culture. 喜蛛 (xǐzhū), for instance, is a kind of long-bodied, long-legged spider you might be happy to see dangling in your room, as it represents 喜从天降 (xǐ cóng tiān jàng), heaven-sent fortune.

One folk story says the Song Dynasty (960-1279) prime minister and litterateur Wang Anshi (王安石) invented the double xi (囍) to describe a situation where two happy events occur around the same time. Wang passed a government exam and got married. Later, 囍 became exclusively associated with weddings as a decorative symbol. On the couple's big day, you will find the character everywhere, from doors and windows to invitations and red envelopes stuffed with money. In marriage, xi is the name of the game: the wedding banquet is called 喜宴 (xǐyàn), wine served is 喜酒 (xǐ jiǚ) and sweets are 喜糖 (xǐtáng). Traditionally, Chinese weddings are regarded as extremely auspicious and can supposedly bring good fortune and drive away evil spirits. So, if an elderly relative is ill, young couples move up the date in the belief that it might help their recovery - a practice called 冲喜 (chōngxǐ).

Another special meaning for xi is "pregnancy", which is commonly referred to as 有喜 (yǒuxǐ), literarily meaning "to have xi". Even morning sickness is called 害喜 (hàixǐ), "to suffer from xi".

Translated by Liu Jue.

Courtesy of The World of Chinese,

www.theworldofchinese.com

The World of Chinese

(China Daily 04/19/2013 page17)

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Phone bookings for taxis in Beijing

Chinese consumers push US exports higher

Seoul delivers ultimatum to DPRK

Boston bombing suspects intended to attack NYC

No let up in home price rises

Bird-watchers undaunted by H7N9 virus

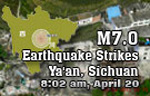

Onset of flood season adds to quake zone risks

Vice-president Li meets US diplomat

US Weekly

|

|