Peddling new solution to old problem

Updated: 2013-09-27 07:01

By Zhang Zhouxiang (China Daily)

|

||||||||

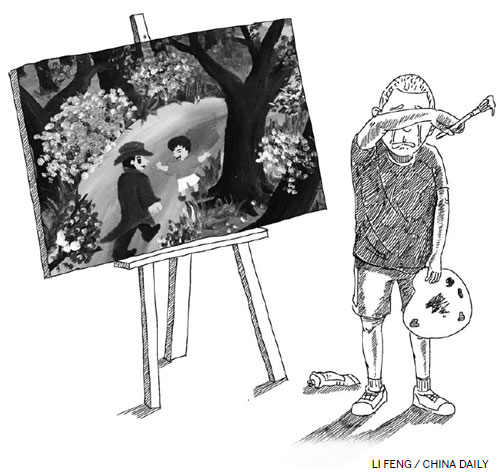

Xia Junfeng, a street vendor, was executed on Wednesday for killing two chengguan (or city management officers) in 2009. Xia, an unlicensed kebab seller in Shenyang, Liaoning province, was detained after being allegedly roughed up by chengguan in May 2009. In the chengguan office, he stabbed the two officers before fleeing the scene.

Many netizens have paid condolences to Xia's family, including his wife and 11-year-old son (which now survives on the meager earnings of Xia's parents), and criticized chengguan for their high-handed and violent behavior with vendors.

But we should understand that the two city management officers were also breadwinners of their families and victims of the tragedy. So instead of despising city management officers, we should reflect on the city management system itself.

Chengguan has been hitting the headlines with increasing frequency because of their conflicts (many of them violent) with unlicensed street vendors. So what is wrong with the chengguan system and how can it be rectified?

According to the latest urban management regulation of Beijing - published in February this year -the duties of chengguan include "maintaining order in the city" and "penalizing unlicensed business". Chengguan is just a part of the bigger mechanism to "manage a city's image".

Street vendors and peddlers are among the most unwelcome elements for chengguan. In fact, many cities have banned peddlers and vendors because "they damage the city's image".

Most of the peddlers are farmers or laid-off workers trying to earn a living. And since a majority of them lack the skills to compete in the job market, they have no option but to rely on peddling and - if they are lucky - manage enough money to start a micro business to keep the home fire burning.

Most peddlers in China cannot afford to rent a stall in a market. A recent Shanghai Municipal Commission of Commerce survey shows that the rent of a stall in a vegetable market accounts for 62-79 percent of the total cost of vegetables. Even in small cities like Yantai, Shandong province, a stall could cost as much as 1,500 yuan a month in 2011, forcing many self-employed people out of markets and into the streets. Ironically, a considerable part of the high cost of stalls is spent on the upkeep of the government's market regulating agencies such as chengguan. And with so many people forced to sell goods on streets, conflicts between vendors and chengguan are bound to happen.

In 2007, Ma Huaide, a professor of administrative law at China University of Political Science and Law, told an interviewer that authorities in some cities wished that all peddlers and vendors disappeared overnight, without giving a thought to their survival. There doesn't seem to be any change in the attitude or wish of the cities' authorities since then.

The conflicts between vendors and chengguan have increased because of the intensified urbanization drive. The number of chengguan in Beijing grew from just more than 100 in 1997 to more than 7,000 (helped by 6,500 assistants) in 2011, according to a member of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference. The same has happened in many other cities, which need more expansive mechanisms to "maintain their image".

The conflicts between vendors and chengguan have become increasingly violent in recent years, leading to serious injuries and even death. On July 17, Deng Zhengjia, a 56-year-old watermelon peddler, died in conflict with chengguan in Linwu, Hunan province.

The fact is, chengguan has failed to maintain order in cities, let alone maintain their image, even after using violent means. Peddlers have no choice but to return to the streets even after being detained or arrested and paying fines. They will continue playing the "cat and mouse" game with chengguan because they have to earn a living.

To end this mindless game, cities' authorities have to find ways to let peddlers and vendors ply their trade. Peddling should be regulated, not terminated.

A middle-aged Chinese snack vendor in New York's Columbia University hit the headlines on websites and in newspapers in June this year. Reports say he earns a decent income. But despite fining him more than $1,000, neither police nor municipal officers have barred him from vending his snacks.

The Columbia University incident sparked a discussion on chengguan: Can Chinese urban regulators follow the example of developed countries and allow peddlers and vendors to ply their trade in part of a city? Many cities are already experimenting with the idea. Authorities in Zhuhai, Guangdong province, have been allowing peddlers in certain districts for a certain period of the day since July 27. The feedback has been promising, and the authorities are planning to extend the policy to the entire city.

Some cities like Chongzhou, Shandong province, and some districts in Beijing, have adopted similar measures. Hopefully, such experiments will act as good examples for other cities to follow. After all, urbanization does not mean denying millions of people the opportunity to earn a living by using public space.

The author is a writer with China Daily.

E-mail: zhangzhouxiang@chinadaily.com.cn.

(China Daily 09/27/2013 page9)

Making a wobbly stand on violence against women

Making a wobbly stand on violence against women

Serena Williams back to Beijing for new crown

Serena Williams back to Beijing for new crown

'Battle of the sexes' to start China Open

'Battle of the sexes' to start China Open

US astronaut praises China's space program

US astronaut praises China's space program

Christie's holds inaugural auction

Christie's holds inaugural auction

Aviation gains from exchanges

Aviation gains from exchanges

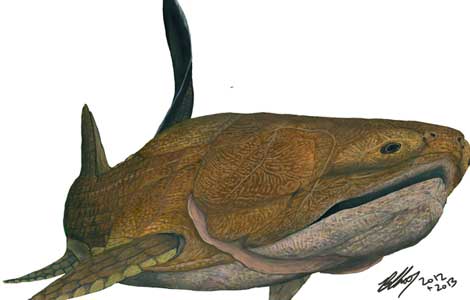

Early fish ancestor found

Early fish ancestor found

Singers' son sentenced to 10 years for rape

Singers' son sentenced to 10 years for rape

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

US arms sales to Taiwan still sticking point

US Senate panel drafting bill to limit NSA spying

Popularity of Brazilian president rebounds: poll

UN to draft resolution on Syria's chemical weapons

China urges package deal on Iran's nuke issue

Can the 'Asian pivot' be saved?

Trending news across China

US firms pin hopes on financial liberalization

US Weekly

|

|