Man with no face transports viewers

Updated: 2015-06-22 08:43

By Wen Chihua(China Daily USA)

|

||||||||

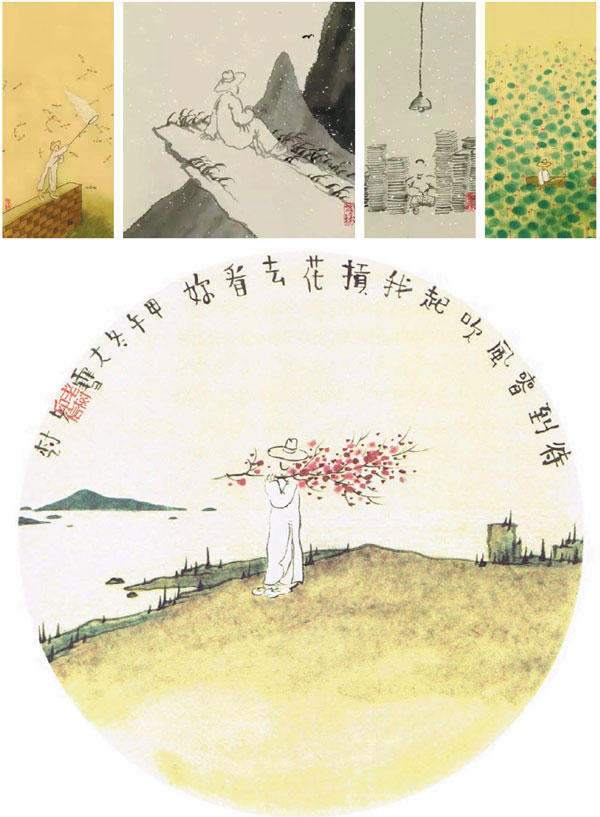

Paintings and poetry by Lao Shu feature Mr Minguo, a featureless but powerful figure living a simple yet profound life

Lao Shu, or "Old Tree", is not a professional painter. Yet, he has gained considerable fame via Chinese social media for his Chinese ink-wash paintings accompanied by his poetry.

His work's popularity has been attributed to subject matter that reflects what people most want today - a slower-paced, leisurely life.

|

Painter Lao Shu's Chinese ink-wash paintings portray a featureless gentleman named Mr Minguo, who wears a long robe and cotton shoes and lives in a dreamy, ideal realm reminiscent of the Republic of China era (1912-1949), and lead viewers to escape momentarily from the bonds of everyday life. Photos Provided to China Daily |

Lao Shu's style is simple and light. But the meaning behind his work is quite profound. The human character in Lao Shu's quiet world is named Mr Minguo.

Portrayed as a gentleman wearing a long robe and cotton shoes reminiscent of the Republic of China (known as "Mingguo" in Chinese) era (1912-1949), he walks along farm lanes, sits under trees, stands by a creek, or leans on a broken wall.

Lao Shu's real name is Liu Shuyong. He is a professor at the Culture & Media School at Central University of Finance and Economics in Beijing. A well-established art critic, Liu, 53, is noted for his sharp and insightful thinking. He is over 1.8 meters tall, with a deep voice and a shaved head. He likes to make fun of himself, saying, "I look like a pig butcher."

And yet, many in his audience say they think of him as a big man who also has a delicate and sensitive heart. He leads them to escape momentarily from the bonds of everyday life, to the dreamy, ideal realm inhabited by Mr Minguo.

In one painting, Mr Minguo holds a large cluster of wild flowers in his arms. He is standing alone, as though waiting for a spring breeze to come, walking slowly, perhaps toward home.

The poem that accompanies the painting reads "picking wild flowers, I put them in a vase, when it is at midnight, the room fills with the spring breeze".

Most scenarios in Lao Shu's paintings have a touch of the unworldly amid mundane depictions of daily life. In another painting, Mr Minguo is shown leaving a farmer's market with a Chinese cabbage in his arms, close to his body, as if holding a bouquet to give to his lover. The verse for the painting reveals Mr Minguo's internal monologue: "Coming into the farmer's market, I catch sight of a cabbage. It looks smooth and tender. I take it home to love."

One critic said having a poem along with a painting suggests that the painting is not powerful or expressive enough by itself.

Lao Shu disagrees. "Painting," he says, "is a visual expression. A poem is a conceptual expression. In classical Chinese brush painting - the most prestigious form of Chinese art, and the province of the literati for centuries - a poem, some calligraphy and the drawing always go together. The relationship of text to the painting is not one interpreting the other. Rather, it's that one is complementing the other. Like the relationship of a pair of chopsticks to a rice ball, the chopsticks cannot make a rice ball larger, and the rice ball cannot provide the chopsticks with any rice. Yet, a rice ball and a pair of chopsticks can be artistically matched perfectly."

Indeed, Lao Shu's work is a new take on literati painting that has changed something innate in the medium.

Traditional literati painting tends not to involve society in order to maintain the painter's sense of a personal, noble and unsullied morality. Vernacular painting, however, actively pursued societal interaction.

His work combines the lines and shading of literati painting with the intervention of vernacular characters.

This is more in keeping with the modern world. Lao Shu notes: "In the past, you could stay in deep mountain seclusion, where you could build a cottage and appreciate the floating clouds, flowing water, and flowers blooming and fading. Now, if you built such a house, officials would find you immediately and demand you demolish it. Living as a recluse is an unrealistic fantasy for intellectuals today."

At the aesthetic level, Lao Shu's painting has broken the rules. Traditionally, the appreciation of literati painting was within the realm of elites only. Viewing such art meant gradually unrolling the work so that the viewers saw the painting little by little. Only when work was completely unrolled could views see the whole image.

In contrast, Lao Shu puts his paintings online, where any viewer can see the entire painting at once. In 2011 he opened Lao Shu Huahua on Sina Weibo, a Chinese micro-blogging website. He posts one painting a day there, and now has over 700,000 followers. Each painting is accompanied with a poem, either a sophisticated piece of self-mockery or a satire pointed at the social reality of modern greed.

He says he was driven to post his paintings on his blog originally because he "hoped that professional artists would comment on the work, either critically or providing inspiration. Unexpectedly, the white-collar community has reacted most warmly." The leisurely life depicted in the paintings coincides with their desire to find a release for their tensions.

In one piece that looks like the landscape painting from an ancient dynasty, Mr Minguo is standing on a hill, above a river. He carries a branch from a peach tree, full of blossoms.

The poem in the painting says: "Waiting till the spring breezes blow, I'll shoulder flowers to see you. I want to tell you all my regrets and my faults. Our love is everlasting in my heart."

The inspiration came from the painter's experience when he was a youngster in his hometown, Linqu county in China's Shangdong province. One day, on the way home from collecting firewood, he encountered a newly married woman going to visit her parents. She carried a package wrapped in a cloth with a bright peony flower pattern. As she was walking along, she stopped suddenly, went to the side of road where a wild peach tree was blooming, picked a flower and pinned it to the cloth.

"When looking back," he says, "the scenes of daily life of my childhood were so poetic, exactly like those described in The Book of Songs, a collection of poetry collected by Confucius."

The most striking characteristic of Mr Minguo is that he has no features: no eyes, no eyebrows, no face.

When he started painting in 1979, the figures he drew all had clear, expressive faces. Those figures were so vivid that some commented that his paintings looked like those of the great masters Qi Baishi and Pan Tianshou. On hearing this, Lao Shu was uncomfortable because "those nice words only mean my painting lacks my own style". He stopped painting in 1985.

In 2007, his father got stomach cancer. Lao Shu could not sleep for days, so he picked up the brush he had put aside 20 years earlier and started painting again.

"When I returned, the first thing I painted was an image of Mr Minguo, standing under a tree, without a face. I found this image so interesting that I have kept this painting style ever since." The image of Mr Minguo without facial features has become the signature of Lao Shu's painting.

Drawing Mr Minguo, he says, is a way to help solve his own problems at a spiritual level. "The private life of my generation, born in the 1960s, has endowed itself with too many grand themes: the significance and the value of life, social obligations and undertakings. Around the age of 40, I began feeling disgusted with such a 'collective personality' imposed on individuals, so I retreated to the internal world. I paint because I personally need to express that internal world. Not for anyone or for anything. I only need to be responsible for the specific life of my own. Just like that, safe and sound."

For China Daily

(China Daily USA 06/22/2015 page6)

Liu visits Houston Museum of Natural Science

Liu visits Houston Museum of Natural Science

Liu meets Tsinghua Youth team in Houston

Liu meets Tsinghua Youth team in Houston

Liu visits CI in Pittsburgh

Liu visits CI in Pittsburgh

Shenzhen Maker Week kicks off

Shenzhen Maker Week kicks off

Chinese wrap up Zongzi to mark upcoming Dragon Boat Festival

Chinese wrap up Zongzi to mark upcoming Dragon Boat Festival

A Chinese Garden in a Sister City

A Chinese Garden in a Sister City

Across America over the week (June 12-18)

Across America over the week (June 12-18)

Liu meets Intel CEO

Liu meets Intel CEO

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Tsinghua students flying high

Chinese Premier emboldens state firms' int'l industrial cooperation

CI in Pittsburgh welcomes

vice-premier

Sichuan and Pittsburgh unveil

new school

Russia, China do not form blocs against anyone: Putin

More than 'greet'

and 'meet'

Liu Yandong meets

Pittsburgh mayor

Innovation competition marks 10th anniversary

US Weekly

|

|