Sands of time shifting for desert community

Updated: 2015-09-18 17:22

By Cui Jia and Mao Weihua(China Daily USA)

|

|||||||||

With just 1,347 residents, Daliyabuyi is the smallest township in the Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region, and until recently it was also the most remote. Now times are changing, thanks to the introduction of satellite TV and cellphones, report Cui Jia and Mao Weihua in Hotan prefecture.

Editor's note: This is the first in a series of special reports to mark the 60th anniversary of the founding of the Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region. Over the coming weeks, China Daily will brings its readers in-depth stories about the lives of the people who live in China's "Wild West", outlining their aspirations and concerns, and the changes in the region during the past six decades.

Memet Turson's face split into a huge grin as he stood in front of the house he built next to the sand dunes of the Taklimakan Desert. As a resident of Daliyabuyi, hidden deep in the world's second-largest desert in the Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region, the sight of an outsider is "a luxury", according to the 60-year-old herder.

When visitors see the local houses built from the wood of the desert poplar, the first question they ask is why the locals don't move out of the desert and enjoy a modern lifestyle.

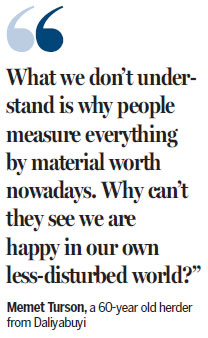

"What we don't understand is why people measure everything by material worth nowadays. Why can't they see that we are happy in our own less-disturbed world?" Memet asked. "A good life is not about money, but about if one really enjoys it. Daliyabuyi is our heaven."

About 400 years ago, 20 Uygur families who were threatened by war left their land in what is now Yutian county in the southern prefecture of Hotan. They followed the Keriya River, which is fed by meltwater from the snow-covered Kunlun Mountains and gradually evaporates in the Taklimakan, a vast, expanse the locals call the "ocean of death".

Fifteen families settled on the river's west bank, while the others stayed on the east. Together, the families named their new home Daliyabuyi, which means "live along the river" in the Uygur language. They started from scratch, finding it difficult to adjust to desert life and exchange farming for herding sheep among the reed bushes.

An historical footnote

They called themselves the Keriya people, and they lived a self-sufficient life in the Taklimakan, using the wood of the desert poplar trees that grow along the riverbank to build houses. They burned rose willows for fuel and heating, and learned to use the hot sands to cook their food.

Eventually, they became cut off from the outside world and became a footnote in history until 1986, when a team exploring for oil reported seeing a "wild man" in the desert and submitted a report to the central government in Beijing.

"They said they had seen saw a man covered in fur and with a tail. It turned out to be a member of the Keriya people wearing his fur coat inside out and carrying an ax on his belt with the handle sticking out at the rear," said Azez Musar, commissioner of Hotan prefecture, who last year visited Daliyabuyi for the first time.

Having been alerted to the presence of the Keriya people, government officials traveled to Daliyabuyi to assess their needs. The residents said they wanted the status of the village to be raised, and in 1989, Daliyabuyi officially became the least-populated township in Xinjiang, Azez said.

The small, lost tribe has grown to 347 households and 1,347 residents. The people, scattered along the river, still use the old survival skills, especially for house construction and cooking, but the old ways are changing significantly even in the remotest parts of Xinjiang.

Modernity arrives

Through the gaps in the tree branches that serve as walls, almost everything is on display in Memet's traditional house: the sheepskin on the floor that allows the family to wipe sand off the soles of their feet, a shiny fridge and photos of traditional English gardens that hang on the walls as decorations.

The houses may look shabby, but they provide perfect ventilation and are cool inside even when the desert absorbs the fierce summer heat.

"Life in the desert is not as harsh as people think. It can be modern too," Memet said, gently patting the fridge he bought in June after the township government installed new batteries to store the excess electricity generated by solar panels and provide constant electricity. When he bought the fridge, Memet abandoned his old "vegetable cellar" - a deep hole he dug in the backyard - and it's now completely filled with windblown desert sand.

Daliyabuyi is 267 km north of Yutian, the county seat, but there are no roads in the desert. Apart from the locals, only skillful drivers, such as Rejef, can take visitors to the township. Rejef's customers include Azez, other township officials and people who are curious about this "Shangri-La of the Taklimakan".

Getting to and from Daliyabuyi remains a challenge, though. The journey takes 10 hours in Rejef's SUV - the fastest means of transportation - but the same trek takes a whole day by motorbike or a week by camel.

The 48-year-old Yutian native knows the desert like the back of his hand and the SUV easily scales the six mountainous sand dunes on the way to the township. The dunes are forcing the river to change its course, and the shifting sands have already raised a section of riverbed above the water level.

"In 1986, it took me 15 days to get to Daliyabuyi in a truck, and I clearly remember that there were only two big sand dunes on the way. The area where people can herd animals has become smaller over the years, but the population has grown," Rejef said, shifting gears as the SUV climbed a dune. "It's more like sailing in the desert than driving."

The Keriya people always stand outside their houses when they hear the sounds of vehicles approaching. They always check to see if the travelers need help and offer them cups of herbal tea.

The part of the Taklimakan nourished by the Keriya River is full of life, including China's biggest forest of wild desert poplars, whose leaves turn golden in autumn. The local government has announced that it will build a 90-km-long road to the forest to attract tourists, but Rejef was unimpressed. "It will quickly be eaten up by the desert," he said.

Tohutroz Memetmin has been head of Daliyabuyi for three years, but the 40-year-old Yutian native still can't get used to the rough and sometimes dangerous journey from the county seat. "During the flood season around July and August, no vehicles can get in, so the township is completely sealed off. Also, sandstorms during the journeys can be life-threatening because there is no mobile reception along the way."

Although there is no coverage in the desert, solar-powered mobile-signal towers have been built in the compound of the township government to connect Daliyabuyi with the outside world. The offices are actually mobile homes, which are cheaper than buildings and easy to move. "No one can afford brick houses here because the cost of transporting bricks is too high, and who knows how many bricks will actually survive the journey. Our offices are unique among government buildings in China," he said.

"The people here are very honest and always look out for each other. There is no violence or terrorist crime here," Tohutroz said. Actually, there was no recorded crime in Daliyabuyi until last year, when 21 locals were arrested for stealing cultural relics from an ancient city buried by the desert and selling them illegally. "They wanted to get rich and move out of the desert," he said.

In the 'Red Mansion'

One of the biggest challenges facing Tohutroz is arranging for residents to attend township meetings because the farthest house from government offices is 130 km downriver. Before satellite phones were installed in every house in 2010, it took at least 10 days to inform the locals, but now it takes just two.

"People used to live even farther downstream, but there is no water there anymore so they abandoned their houses. They know how important and fragile the environment is in the Taklimakan," he said.

No matter how far they live from the center of the township, the residents always try to attend the small mosque near the government offices for Jumah, the most important prayers of the week, held every Friday. As a result, Tohutroz arranges for township meetings to be held before or after prayers, and photos of terrorist suspects are put on the wall outside the mosque. There is no place too remote when it comes to apprehending suspects in Xinjiang, Tohutroz said.

The start of the holidays saw the quiet township burst into life as the children and young people returned from boarding schools and colleges in Yutian and Hotan.

The smaller children love to play soccer on the sand dunes, while the adults, such as 18-year-old Alim Mehilik, prefer to spend their evenings playing pool with friends at the "Red Mansion", a small club that opened in June.

The club is actually a mobile home that's been painted red, because the color stands out in the desert so no one can miss the place. It boasts three pool tables and, unusually for a Muslim community, a bar. "See, Daliyabuyi is a big city now," joked Alim, who studies vehicle maintenance in Hotan.

"Life in the city and in Daliyabuyi are completely different - not better, not worse, just different" he said, adding that he plans to find a job as a mechanic in Yutian.

Memet has been to the county seat many times, but he prefers life in Daliyabuyi. "We build our houses from desert poplars, drink water from the well and use solar panels to generate electricity, and it doesn't cost us a thing. Everything costs money outside the desert," he said.

Memet said the Keriya people know how to live in harmony with nature and that's why they have survived in the desert for more than 400 years. "We never cut down trees if we don't need to, or herd too many sheep. Our houses are always quite far from each other to ensure that the sheep don't eat all the reed bushes in one area."

High hopes

In addition to herding sheep, Memet's son Abudulrehit Memet, runs a grocery store on the township's 500-meter commercial street, where chilled drinks are the biggest sellers on hot summer days. The 37-year-old's two sons are both studying at the primary school in Yutian. "I want to make more money so my sons can go to university and my father can make the pilgrimage to Mecca," he said.

The gradual drying-up of the river and the aggressive invasion of the Taklimakan have resulted in 50 families moving away for good and beginning new lives in government-built resettlement houses on the outskirts of Yutian. Thirty more families have signed up to relocate this year.

"They will have to learn how to farm again, which will not be easy. The young people prefer to move out of the Taklimakan, while the elderly insist on staying. Either way, we respect and support their choices," Tohutroz said.

Despite living so far from the modern world, Memet's greatest joy is to watch the national and international news on his satellite TV. "We now live the simple life we desire, but are more connected to the outside world than ever before. Life is good in Daliyabuyi," he said, flipping channels with the remote control.

Contact the writers at cuijia@chinadaily.com.cn and maoweihua@chinadaily.com.cn

|

Women make a fire to cook in Daiyabuli township. |

|

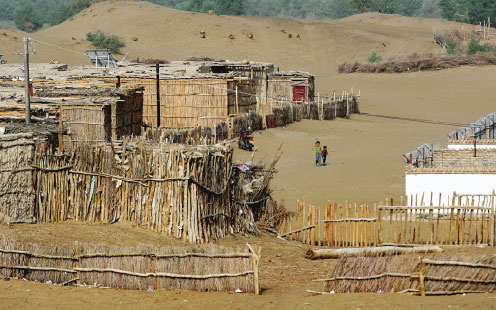

Local people use the wood of the desert poplar to build houses in Daliyabuyi, Hotan prefecture, the Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region. It's prohibitively expensive to transport building materials to the desert township because it is not connected to the outside world by road. Photos by Wang Zhuangfei / China Daily |

|

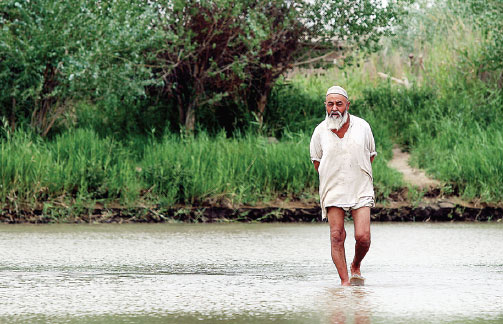

A man walks through a shallow river to welcome visitors after hearing the sound of an SUV engine. |

|

Residents pray with the Imam. |

|

Residents wait to collect wheat flour distributed by the local government. |

|

A women checks photos on a digital camera. |

(China Daily USA 09/18/2015 page10)

- UN chief: Those blocking fleeing refugees should 'stand in their shoes'

- Hungarian riot police detain migrants

- IOC announces five cities bid for 2024 summer Olympic

- Japan opposition to halt vote on security bills

- Japan protesters rally as security bills near passage

- Australia launches first air strikes against IS

Messy dorm earns grueling punishinment for students

Messy dorm earns grueling punishinment for students

Seven killed as rainstorm triggers landslide in SW China

Seven killed as rainstorm triggers landslide in SW China

Chinese armed forces arrive in Malaysia for joint military exercise

Chinese armed forces arrive in Malaysia for joint military exercise

Top 10 M&A deals between China and US in 2015

Top 10 M&A deals between China and US in 2015

Delicious bites in record-breaking sizes

Delicious bites in record-breaking sizes

Popular Chinese dishes in the US

Popular Chinese dishes in the US

Evacuation ordered after M8.3 earthquake hits Chile’s coast

Evacuation ordered after M8.3 earthquake hits Chile’s coast

Donate sperm to get an iPhone 6s

Donate sperm to get an iPhone 6s

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Economy worries prompt Fed to hold rates steady

Google demos online marketing strategies to support Chinese SMEs

The ancient city takes a new route along the Silk Road

Villagers angry at verdict on fatal fire

Promoting the landscapes of China

Uber's Chinese rival backs US rival Lyft

Positive tone struck for Xi's US visit

Xi to press case for Bilateral Investment Treaty

US Weekly

|

|