Growth and reform

Updated: 2016-01-01 08:16

By Andrew Moody(China Daily Africa)

|

||||||||

This will be a crucial year if China is to meet its target of joining the high-income club of nations, say leading economists

The Chinese government is set to reconfirm in its Five-Year Plan (2016-20) in March the aim of becoming a "moderately well-off society" by 2020.

This will involve breaking out of the so-called middle-income trap that has ensnared developing countries, particularly in Latin America.

The government has set itself a target of doubling its 2010 GDP and per capita income by 2020.

How the economy performs over the next 12 months will partly determine how this goal can be achieved.

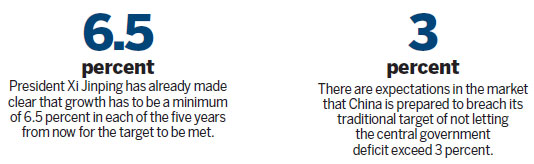

President Xi Jinping has already made clear that growth has to be a minimum of 6.5 percent in each of the five years from now for the target to be met.

The government will also decide in March whether to stick to its 2015 growth target of "about 7 percent" for the year ahead or to lower it, as some expect, to somewhere near or at the 6.5 percent mark.

The ambitious overall plan target, however, comes at a time when the Chinese economy faces many challenges as well as global economic uncertainty.

At the Central Economic Work Conference, a key economic meeting held in Beijing in December, the government made clear its priorities for the year ahead.

It wants to embark on major supply side reforms, tackle industrial overcapacity, particularly in the state-owned enterprise sector, and free up capital and labor to be redeployed to faster growing areas of the economy.

It also wants to tackle the key issue of a massive oversupply of unsold homes, which is holding back the property sector - a key driver of the overall economy, fueling demand for steel, concrete and household goods.

To do this, it is to press ahead with reforms to the household registration scheme, or hukou, to allow people to move from rural areas to the cities to buy up existing housing stock.

Tackling local government debt, a critical weakness of the economy, and allowing municipalities to issue bonds and develop more sustainable funding mechanisms will also be a central plank of policy.

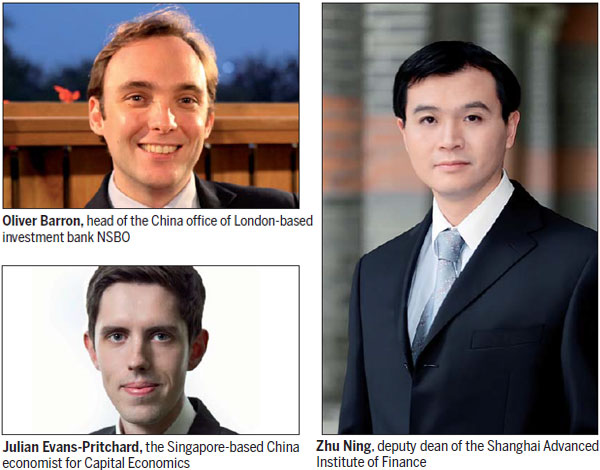

Oliver Barron, head of the China office of London-based investment bank NSBO, believes policymakers will take the necessary steps to achieve at least 6.7 percent GDP growth in 2016.

He thinks that if the government is too bold on SOE reform, it could undermine its overall growth strategy.

"Efforts to tackle stubborn industrial overcapacity and push forward SOE reform are a double-edged sword. They are necessary to secure sustainable growth in the long term but will put more downward pressure on economic growth in the short term," he says.

"If reform is carried out too rapidly, there is significant downside risk that growth would fall below the expected plan target."

George Magnus, associate at the Oxford University China Centre and a leading expert on the Chinese economy, says the December conference in Beijing unveiled a new direction in government policy.

He says measures to tackle SOE inefficiency, particularly the so-called zombie companies, as well as reducing corporation tax and initiatives to support certain industry sectors appeared to be a serious attempt to set a new course.

"They span serious measures to promote efficiency and boost total factor productivity."

He expects the government to set a target of 6.5 percent for GDP growth in March, below that of 2015.

"We are looking at a situation where the growth target remains the top priority for policymakers. We shouldn't ignore the traditional tools of policy that will be deployed to try and support this."

One of the main engines for growth next year is likely to be a more expansionary fiscal policy.

Official statements from the Central Economic Work Conference spoke of a more "proactive" as well as a "flexible" fiscal policy. Fiscal policy refers to taxing and spending by governments.

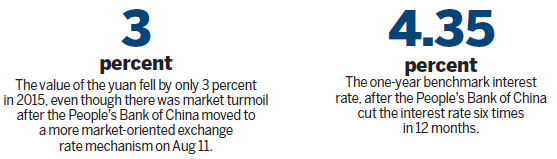

This would represent a shift in direction since there has been recent emphasis on monetary policy as the main economic tool. Monetary policy refers mainly to management of interest rates. In October, the People's Bank of China cut the one-year benchmark interest rate by 0.25 percent to 4.35 percent, its sixth such move in 12 months.

There have been expectations in the market that China is now prepared to breach its traditional target of not letting the central government deficit exceed 3 percent.

Louis Kuijs, head of Asia economics at Oxford Economics, who is based in Hong Kong, says this is partly because the government has taken monetary policy as far as it will go.

"We are starting to see more reliance on fiscal policy rather than just monetary policy to stimulate growth.

"I think this is welcome because China has really pushed the envelope in terms of credit growth and there have been a lot of concerns in the market about credit growth becoming too rapid."

Kuijs, a former World Bank economist, believes the fiscal stimulus will be used to direct more spending on infrastructure.

"I think this will help compensate for the fact that local governments, because of their debt position, have been more constrained in this area," he says.

"The government may also take over some expenditure responsibilities that have been traditionally assigned to local governments, one of which could be taking control of a new nationwide pension."

Julian Evans-Pritchard, the Singapore-based China economist for Capital Economics, a consultancy, also expects a more expansionary fiscal stance, although he still believes monetary policy will be a significant policy tool.

"We still expect some monetary easing next year, although mostly at the beginning. Monetary policy has already eased quite a lot and I don't think we have seen the full impact of this yet. I think we are going to see growth looking better and improving as a result of the measures already taken."

Evans-Pritchard also believes the government will probably set a 7 percent growth target for 2016 again but believes that 6.5 percent would be a more positive sign.

"I think that would be a clear sign that the people in the Party who are pushing for less emphasis on growth would have won a concession.

"We are getting to a position where it is not easy to control growth. It has been slowing because investment has been slowing and this is because the rate of return on investment has been falling because the capital stock is already quite large. There is not really much the government can do about that."

Liu Zhiqin, senior fellow at the Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies at the Renmin University of China in Beijing, insists the government is relying on three main drivers for growth.

These consist of the performance of Internet companies such as Alibaba and Tencent, the Belt and Road Initiative, and the Chinese dream of creating an affluent consumer society.

"I think there has to be a question as to how much momentum they can give the economy in the short term. It is not clear whether the Internet can really be an engine of the economy since it is more a tool and a facilitator," he says.

"The Belt and Road Initiative could deliver but over a much longer time frame, like 10 or 15 years. I don't think there is any short-term dividend."

Liu believes the economy will achieve growth of 6.5 or 6.6 percent in 2016 but doubling the 2010 GDP level by 2020 might prove difficult.

"I think the economy could be heading into some very stormy weather over the next five years and will face many challenges. I think this first year will be crucial to the overall plan being delivered."

He believes a big policy risk will be the reform of state-owned enterprise and the difficulties in engineering genuine market reform.

"The problem with these enterprises is that they do not really operate in a free-market environment. Very often the government is the main customer, buyer and even supplier, so to expect them to suddenly act like their Western counterparts is very difficult. This could be a very long process."

The new year begins against the backdrop of the US Federal Reserve Bank's move on Dec 16 to increase its benchmark rate by 0.25 percentage point.

It was the first tightening of monetary policy in the West for seven years and could be one of a number of such rises in 2016.

Paul Mason, author of Postcapitalism: A Guide to Our Future, and also economics editor of Channel 4 News in the United Kingdom, says this could be a test for the global economy.

"We are not yet at the peak of the recovery cycle and we will find out whether the global economy can survive without stimulus because the Americans have finally withdrawn it."

Regardless of any rate increases, it is clear that the US economy, which reported 2 percent third quarter growth on Dec 22, cannot build up any real momentum while there are headwinds elsewhere.

"Unlike 20 years ago, the US economy cannot really power ahead if the rest of the world is not moving, and I think that became obvious over the last year and was reflected by the difficulties the Fed had in beginning this tightening process, postponing a widely expected interest rate move in September," adds Kuijs at Oxford Economics.

Higher US interest rates could lead to further capital flight from China and other emerging markets and also have a destabilizing effect on the Chinese yuan.

There was market turmoil after the People's Bank of China moved to a more market-oriented exchange rate mechanism on Aug 11 but despite this, the value of the yuan fell by only 3 percent in 2015.

Bank of America Merrill Lynch, however, is forecasting an overall 10 percent decline in the yuan-dollar exchange rate.

Zhu Ning, deputy dean of the Shanghai Advanced Institute of Finance and author of the forthcoming book, China's Guaranteed Bubble, believes the authorities will intervene to prevent this.

"There are certainly such expectations out there in the market but I think the PBOC will be really reluctant to let the market get what it hopes for," he says.

"Even though everyone knows it has to go down a certain amount, the PBOC still has a large amount of reserves on hand to achieve a series of technical depreciations rather than a large one-off devaluation."

The risks in the global landscape are different from what they were 12 months ago.

Then the biggest focus was on Europe and whether Greece might blow the euro apart, whereas this year the biggest concern is likely to be the emerging economies.

Countries such as Brazil, Russia, Saudi Arabia, South Africa and Nigeria have all been hit hard by falling commodity prices and could prove a drag on global growth.

"Last year it was all about Greece but I think now, although the problems in Greece have certainly not got any better, there has been this decoupling in the sense of what happens there might not have wider repercussions. Greece may not be part of the euro forever but there might be less spillover elsewhere if it leaves," says Kuijs.

Evans-Pritchard of Capital Economics agrees emerging markets are now the major concern.

"Economies like Brazil and Saudi Arabia have really struggled over the last year because of lower oil prices. Despite all the attention on China and its slowing growth, it benefits from lower commodity prices and is in a good position to weather the storm this year."

Zhu at the Shanghai Advanced Institute of Finance, however, believes the impact of falling commodity prices is more nuanced for China.

"China does get some positive feedback effects from commodity prices falling but some of these emerging economies have become important markets for China and this could be bad news for the country's exports," he says.

Economics commentator Mason expects growth in China to fall in 2016 but does not expect any hard landing.

"For me, the outlook for China is long-term positive. I do not see any doom-laden scenario."

He believes even if China does experience investment bubbles such as with the stock market crash in 2015, it is still left with tangible assets that will continue to drive growth.

"Underlying everything you have real things. There are real high-speed trains, there are new bridges, there is new housing on a vast scale. Whatever happens this physical stock of infrastructure will remain."

andrewmoody@chinadaily.com.cn

|

A container terminal at the port of Qingdao in Shandong province. The Chinese economy faces many challenges including global economic uncertainty. Provided to China Daily |

|

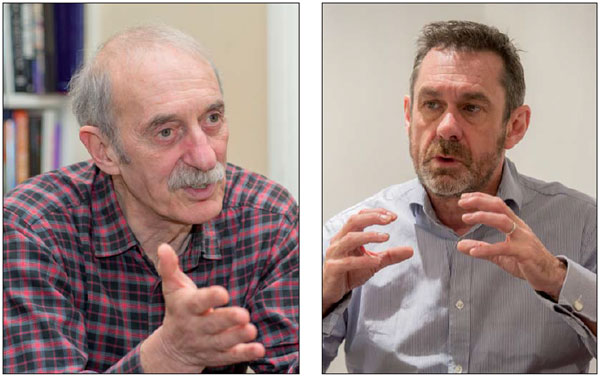

From left: George Magnus, associate at the Oxford University China Centre and a leading expert on the Chinese economy, and Paul Mason, author of Postcapitalism: A Guide to Our Future and also economics editor of UK's Channel 4 News. Photos by Nick J.B. Moore / For China Daily |

(China Daily USA 01/01/2016 page4)

- Top planner targets 40% cut in PM2.5 for Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei cluster

- Yearender: Predictions for 2016 through 20 questions

- Asia's largest underground railway station opens in Shenzhen

- Shanghai bans drug-using actors, drivers

- Clamping down to clean up the air

- Yearender: Ten most talked-about newsmakers in 2015

- Over 1 million refugees have fled to Europe by sea in 2015: UN

- Turbulence injures multiple Air Canada passengers, diverts flight

- NASA releases stunning images of our planet from space station

- US-led air strikes kill IS leaders linked to Paris attacks

- DPRK senior party official Kim Yang Gon killed in car accident

- Former Israeli PM Olmert's jail term cut, cleared of main charge

Yearender: China's proposals on world's biggest issues

Yearender: China's proposals on world's biggest issues

NASA reveals entire alphabet but F in satellite images

NASA reveals entire alphabet but F in satellite images

Yearender: Five major sporting rivalries during 2015

Yearender: Five major sporting rivalries during 2015

China counts down to the New Year

China counts down to the New Year

Asia's largest underground railway station opens in Shenzhen

Asia's largest underground railway station opens in Shenzhen

Yearender: Predictions for 2016 through 20 questions

Yearender: Predictions for 2016 through 20 questions

World's first high-speed train line circling an island opens in Hainan

World's first high-speed train line circling an island opens in Hainan

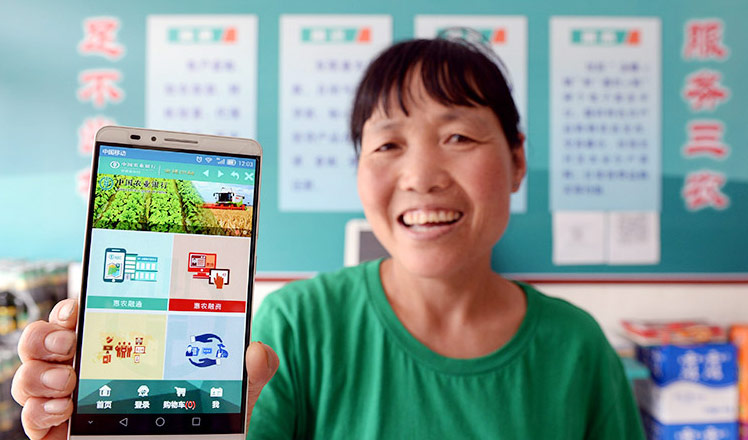

'Internet Plus' changes people's lifestyles in China

'Internet Plus' changes people's lifestyles in China

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Shooting rampage at US social services agency leaves 14 dead

Chinese bargain hunters are changing the retail game

Chinese president arrives in Turkey for G20 summit

Islamic State claims responsibility for Paris attacks

Obama, Netanyahu at White House seek to mend US-Israel ties

China, not Canada, is top US trade partner

Tu first Chinese to win Nobel Prize in Medicine

Huntsman says Sino-US relationship needs common goals

US Weekly

|

|