A Chinese relic finds a new home in US

In Salem, a city that represents a dark period in US history, sits Yin Yu Tang, believed to be the first antique Chinese house to be dismantled and re-erected in the United States, Hezi Jiang and Wang Linyan reports from Salem, Massachusetts.

Enter the Witch House and you will be in 17th century Salem, Massachusetts, site of the infamous witch trials, presided over by the house's owner, Judge Jonathon Corwin, a Salem merchant.

Enter the Yin Yu Tang, a 7-minute walk away, and you will be in a stately 16-bedroom wooden house built during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) by a prosperous merchant surnamed Huang.

The Witch house represents a dark time in US history. Panic and hysteria in the coastal town led to more than 200 people being accused of practicing witchcraft, with 20 men and women - being hanged.

The 200-year-old Huang house - brought to the US from China in 2003 and re-erected at the Peabody Essex Museum (PEM) - offers a perspective on Chinese art, architecture and culture.

The two-story house was originally located in Huang Cun - a rural village of 200 people, most of whom are surnamed Huang - near the Yellow Mountain in southern Anhui province.Since the early 1800s, it was home to the Huang family for eight generations, with as many as three generations living in those 16 bedrooms at one time.

As Daisy Yiyou Wang, PEM's curator of Chinese and East Asian art, put it, the house, also known as Hall of Plentiful Shelter, has a "transporting power".

"It engages all your senses," she said. "You feel that you are traveling in time and space."

Wang said Yin Yu Tang reminds her of her grandmother's house, especially the strong smell of wood, and on her first visit to it, she got so nostalgic that she cried.

Inside, the rooms appear as if the Huang family had just left the house for a walk or for an opera in the village.

A blue traditional Chinese jacket is hung by the windows on the second floor overlooking a courtyard. Mahjong cubes rest in a box on the floor.

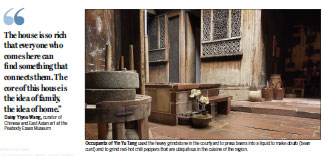

Dried red peppers sit in a bamboo basket.

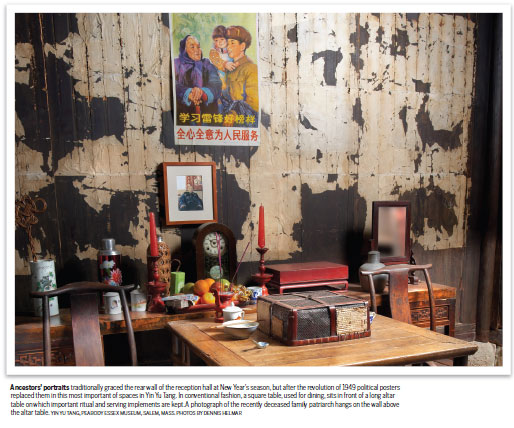

Other details reveal the house's history. There are chalk writings on the wood walls from the "cultural revolution" (1966-76) period. Red diamond-shaped paper painted with the Chinese character double "Xi" or "happiness" has faded to white. It is attached to the door of a bedroom where a newlywed couple stayed.

Among the 700 objects the house came with are intricate and rusted hairpins and a porcelain urinal.

"It's a labor of love and story of serendipity," Wang said. "It's a story of many, many people and institutions who supported this project."

Obtaining the house for the move to Salem was "pretty accidental," said Nancy Berliner, who was PEM's curator of Chinese and East Asian art. In 1996, she was going to villages in China doing research on vernacular architecture. When she was in the village of Huang Cun, she went by Yin Yu Tang but nobody was home.

Later, she returned to the village, and members of the Huang family were there discussing what they should do with the house because all the family members had moved to bigger cities. Nobody was living in it or planned to live there.

Jokingly, they asked Berliner, "Do you want it?"

"I thought at the moment that the house would be fantastic for the museum in America," she said."I realized that the way for Americans to really understand Chinese culture and Chinese people was through everyday residential architecture."

"The way to understand the people of another culture is through their home, how they live," she said.

The local cultural relics administration was seeking a US cultural institution to help increase international awareness of traditional architecture from its region. An agreement was established with PEM to move the house to the US and to help protect and promote the region's local architecture.

It took seven years from when Berliner first saw the house to when it was opened to the public in 2003 at PEM. No part of the process was easy - negotiation, dismantlement, transportation, preservation and reassembly.

Museum officials declined to provide the cost of the Yin Yu Tang project, but according to a New York Times story right before the house was opened, people close to the project at the time said that it could easily cost $15 million, including fees paid to the local Chinese government and money to restore a 1531 shrine and three other local houses.

Nineteen crates holding the house were transported by truck through the mountains to Shanghai.

"The village, at the time, was in a remote area in China. There wasn't even a proper road for the trucks to get out. So we actually had to build the road in order to facilitate the process," said Wang.

From Shanghai, the crates embarked on a months-long journey to New York via the Panama Canal.

They were taken to a large warehouse 30 miles from Salem and unpacked: 2,735 wooden components, 972 stones and more than 60,000 bricks and tiles.

Conservation work soon began with carpenters and stone masons traveling from Anhui province where the house was located to make repairs, including joining old deteriorated wood to new wood and patching broken stones. The project also involved historic house preservation specialists in the US.

"It was a huge international collaboration and an opportunity for both sides to learn from each other," said Wang.

Yin Yu Tang consists of two halls separated by a central courtyard. The South hall was considered more prestigious because its rooms get more sunlight and thus more yang energy - nature's masculine principle. The downstairs of each hall was considered better than the upstairs.

In China, family members were allotted rooms based on their status within the family. The older generation had better rooms than the younger generation, and older sons ranked higher than younger ones.

Unmarried daughters lived in upstairs rooms until they married and moved into their husbands' homes. Younger daughters often lived in rooms with their parents or grandparents.

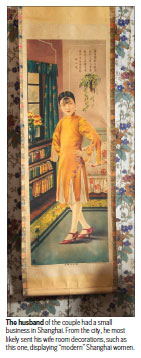

Berliner and Wang also focused on showing a slice of life of the people living in the house. Objects are displayed, including cleaning towels and bedding, on a rotational basis to ensure the longevity of the objects.

"The house is so rich that everyone who comes here can find something that connects them. The core of this house is the idea of family, the idea of home," said Wang.

The PEM team studied the letters, photographs and family documents of the Huangs to learn how they lived in the house.

A household ledger lists expenditures by the family from 1922 to 1927. Among them, an ancestral portrait commissioned in December 1925 for one silver dollar and a pair of songbirds for three silver dollars in October 1922, and 20 copper cents spent on an operain February 1922.

Because Yin Yu Tang was a large house, people from more distant villages would spend the night there after military training during the cultural revolution. Chalk marks outside a room indicate that 16 women from a nearby village were assigned to sleep there.

Two small palm trees in the central courtyard didn't come from Huang Cun, but were donated by a local Salem resident of Chinese descent whose great-grandfather was one of the first Chinese sailors in the region. He wanted to honor his Chinese ancestry by donating the trees to the museum, and he visits Yin Yu Tang every two weeks to water them.

"The house is growing with us here. How people interact with it actually adds to the history of the house," said Wang.

Each year Yin Yu Tang receives about 50,000 visitors. Nearly one million have visited the Chinese house since it opened. Entrance to the PEM is $20, and admission to Yin Yu Tang is an additional $6.

Wang and Berliner have led many tours of the house.

Berliner once welcomed a Huang descendant to the house who worshiped his ancestors and visited the bedroom where his parents got married. The marriage furniture is still there.

"He said to me over and over again that it's such a wonderful way to preserve the house and the family history," said Berliner.

"It's gratifying to see Americans, non-Chinese suddenly have a sense of Chinese people's lives and histories and culture. It's also gratifying to see Chinese visitors feel that the house has preserved a time and a type of space of Chinese culture," she said.

Contact the writers at hezijiang@chinadailyusa.com

(China Daily USA 02/10/2017 page1)