When a bonus is time at home

Updated: 2013-07-14 08:05

By Catherine Rampell (The New York Times)

|

||||||||

|

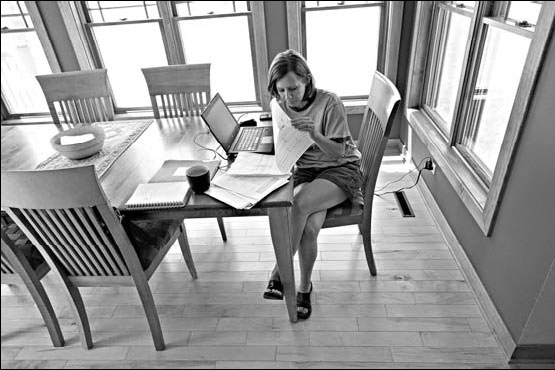

Sara Uttech said her work schedule, which includes working one day a week at home, allows her to juggle all of her responsibilities. Darren Hauck for The New York Times |

FALL RIVER, Wisconsin - Sara Uttech has not spent much of her career so far worrying about "leaning in." Instead, she has mostly been hanging on, trying to find ways to get her career to accommodate her family life.

Ms. Uttech, like many working mothers in the United States, is a married college graduate, and her job running member communications for an agricultural association helps put her family near the middle of the nation's income curve. But she finds climbing a career ladder less of a concern than having a job that offers paid sick leave, flexible scheduling and the opportunity to work fewer hours.

"I never miss a baseball game," said Ms. Uttech, uttering a statement that is a fantasy for millions of working parents in America. (This attendance record is even more impressive when you realize that her children play in upward of six games a week.)

Ms. Uttech wants a rewarding career, but more than that she wants a flexible one. That ranking of priorities is not necessarily the one underlying best-selling books like Sheryl Sandberg's "Lean In," which advises women to seek out leadership positions, throw themselves at their careers, find a partner who helps with child care and supports their ambition, and negotiate for raises and promotions.

Ms. Uttech has done some of those things, and plans to do more as her children (two sons, ages 8 and 10, and a 15-year-old stepdaughter) grow older. Already she has been willing to travel more for trade shows and conferences; last year she made four trips. But probably the career move she is proudest of - and the one she advocates the most - is asking her boss to let her work from home on Fridays.

"People have said to me, 'It's not fair that you get to work from home!" she said. "And I say, 'Well, have you asked?' And they're like, 'No, no, I could never do that. My boss would never go for it.' So I say, 'Well you should ask, and you shouldn't hold it against me that I did.'"

Not everyone aspires to be an executive at Facebook, like Ms. Sandberg. Unaccounted for in the latest books offering leadership strategies by and for elite women is the fact that only 37 percent of working women (and 44 percent of working men) say they actually want a job with more responsibilities, according to a survey from the Families and Work Institute, a nonprofit organization based in New York. And among all mothers with children under 18, just a quarter say they would choose full-time work if money were no object, according to a recent New York Times/CBS News poll.

By comparison, about half of mothers in the United States are actually working full time.

Ms. Uttech, a chipper 42-year-old with a communications degree from the University of Wisconsin-Whitewater, has worked for the Alliance of Crop, Soil and Environmental Science Societies for about 11 years. She has also become an increasingly important source of income for her family, particularly in the years since the housing downtown hurt her husband's construction business. She has had to be resourceful to financially support her family while still doing everything that is important to her as a parent.

Step one was to help persuade her children's school to start an affordable after-school program.

Step two has been to just be really productive in her hours both inside and outside the office.

On a recent Tuesday, which she said was broadly representative of most workdays, she rose at 5:45 a.m. and did a load of laundry. Soon she was wielding the hair dryer in one hand and a son's school permission slip in the other; running to the kitchen to pack lunches; and then driving the children to school at 7:15 a.m. before commencing her 40-minute commute to the office, where she arrives a little after 8. She heads back out - often directly to the baseball field - at 4:30 p.m.

On Sundays, she teaches at her church, and then prepares most of the meals for the rest of the week. And she emphasizes that she gets a lot of help: from her husband, Michael, who picks the boys up from their after-school program, and spends many evenings coaching their sports teams; and from other family members, who live nearby and help watch the children during school vacations.

"I really don't want people to come away from my story thinking that I've figured it out, or that I have the answers for anyone else," she said.

She acknowledges, though, that asking about working from home some days was a career risk.

Ms. Uttech approached her boss several years ago about working from home on a trial basis: just on Fridays, and just for a summer, when the office was on shorter Friday hours anyway. She was still actively engaged in office work, including e-mails and conference calls - but could also throw a load of laundry in the washer on a quick break, and didn't have to endure the long commute.

She found the courage to ask about the arrangement after consulting with other women who were in a book club she was in. It is her time, she says, "to just be a woman for a few hours, not a worker and not a mom or any other title."

At a recent Monday evening meeting of the book club, five women met at the Uttechs' house at about 6 p.m. After discussing the books they had read for about a half-hour, they spent the rest of the night talking. At some point that evening, the conversation turned to career advice - how to approach a boss about getting a raise, say, or working part time.

That's what Angie Oler, a research specialist at a lab at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, 38, did when her first child was born four years ago; lately, though, her boss has been pressuring her to return to work full time. "If it were up to me," Ms. Oler said, "I would never ever go back to full time. Never ever ever ever in a million years."

Ms. Uttech's Friday telework arrangement went smoothly for a few summers, and eventually she got the courage to ask about staying home on Fridays year-round.

She says the greatest "pearl of wisdom" she can offer other working parents is to not be afraid to ask for such accommodations.

Certainly, Ms. Uttech's experience may not be representative. She was lucky to work under managers who were especially receptive to a flexible schedule request.

Her supervisor, Susan Chapman had in a previous position encouraged other employers to set up telecommuting arrangements to create job opportunities for people with disabilities. And the agricultural association's chief executive, Ellen Bergfeld, had also set the tone that work-life balance was important.

Not all employers are so accommodating. Only about a third of employers allow at least some of their employees to work from home on a regular basis; just 2 percent allow all or most of their employees this option, according to the 2012 National Study of Employers conducted by the Families and Work Institute.

Ms. Uttech says she thinks - or at least hopes - that someday motherhood will be viewed by employers as an asset.

"Because I'm a mom I know how to multitask, and I have all these other skills I didn't have before like juggling, mentoring, educating, problem-solving, managing," she said. "And I'm so much more productive now during the hours when I am working. Motherhood should be a feather in my cap, not a drawback."

The New York Times

(China Daily 07/14/2013 page9)

'Despicable' minions upset Depp's 'Lone Ranger' at box office

'Despicable' minions upset Depp's 'Lone Ranger' at box office

'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Former S.A President confident of Mandela

US seeking direct nuke talks with Iran

DPRK blames ROK for aborted talks

27 killed, 77 wounded across Iraq

Death toll rises to 43 in SW China landslide

Soulik batters Taiwan, Fujian coast

French train derailment kills six

7 peacekeepers killed in Darfur

US Weekly

|

|