A fateful knock at the door

Updated: 2015-11-16 08:05

By Raymond Zhou(China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

|

WANG XIAOYING/CHINA DAILY |

The flow of culture is often amorphous. It is very difficult to trace the cloud-like drifting of a foreign cultural influence, especially during times of upheavals. But there are moments and figures that stand out, like signposts, that point to a trend larger than themselves.

On March 26, 1977, Beethoven's Fifth Symphony was played at Beijing's Cultural Palace of Nationalities, with the final two movements broadcast live through radio and television. Norman Lebrecht, a renowned classical music critic, happened to be in Hong Kong that day and caught the broadcast. He ran down the hotel corridor and into the bar, yelling "The 'cultural revolution' is over!"

This little incident is chronicled in the new book Beethoven in China: How the Great Composer Became an Icon in the People's Republic. Meticulously researched and affectionately written by Jindong Cai and Sheila Melvin, it offers a cornucopia of details about how Beethoven, of all Western musicians, turned into a barometer for China's political climate.

Li Delun, the conductor of that performance, was granted permission only three days before the concert-and by nothing less than the standing committee of the Communist Party Politburo-to play Fate, as this symphony is popularly known.

The official newspaper was wary and printed only the Chinese music in the program. Still, music lovers found out and scrambled for tickets while foreign press agencies reported on the symbolic significance of the inclusion of the Beethoven symphony, write Cai and Melvin.

I still remember the early post-cultural revolution years when Fate was the most famous symphony in China, with every radio show incessantly drumming home the message that the opening bars of the symphony signify "the knocking of fate on your door".

But little did I know that Beethoven was played before the "cultural revolution" ended in 1976. Which leads to the most engrossing tidbit in the book: Jiang Qing's insistence on Beethoven's Sixth (Pastoral) Symphony from the Philadelphia Orchestra's historic tour of China in 1973.

Her choice was not relayed to the orchestra until the American musicians had already landed in Shanghai. Conductor Eugene Ormandy had chosen the Fifth, but the Chinese side repeatedly broached the Sixth, without realizing that the maestro had an aversion toward this particular piece and they had not brought the scores anyway. Nor did the American negotiators realize that the Sixth was the choice of Madam Mao.

Eventually, the American representatives had to come up with an impromptu but very "politically attuned" interpretation to change Ormandy's mind. It went like this: the Pastoral themes represented peasant life in the countryside. The storm suggests the peasant revolution China had been through. And the triumphant end of the symphony should be interpreted as the new world that is China in its current state.

- Locals have tradition of drying foods during harvest season

- Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei govts to cooperate on emissions control

- Web promotion of prostitution to be targeted

- Two more spells of smog predicted to sweep North China

- Glass bridge in grand canyon of Zhangjiajie under construction

- Road rage cases pose huge safety challenge

Can Chinese ‘white lightning’ make it in US?

Can Chinese ‘white lightning’ make it in US?

Gunmen go on a killing spree in Southern California

Gunmen go on a killing spree in Southern California

Chinese, South African presidents hold talks to cement partnership

Chinese, South African presidents hold talks to cement partnership

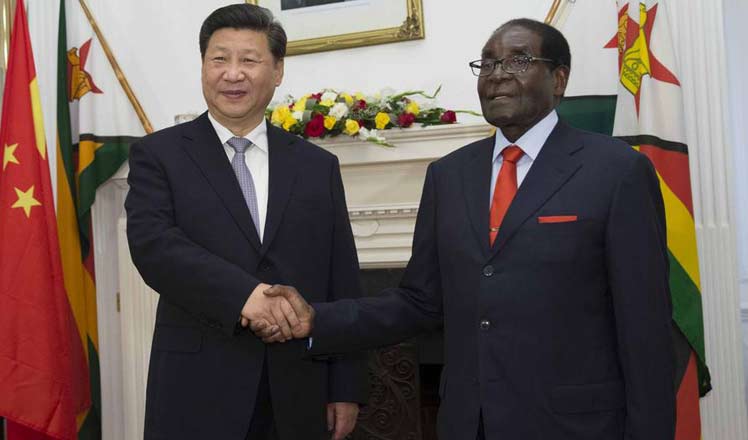

China, Zimbabwe agree to boost cooperation

China, Zimbabwe agree to boost cooperation

First lady visits Africa's 'new window' on China

First lady visits Africa's 'new window' on China

BRICS media leaders to secure louder global voice

BRICS media leaders to secure louder global voice

Western science in the eyes of Chinese emperors

Western science in the eyes of Chinese emperors

Top 10 smartphone vendors with highest shipments in Q3 2015

Top 10 smartphone vendors with highest shipments in Q3 2015

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Shooting rampage at US social services agency leaves 14 dead

Chinese bargain hunters are changing the retail game

Chinese president arrives in Turkey for G20 summit

Islamic State claims responsibility for Paris attacks

Obama, Netanyahu at White House seek to mend US-Israel ties

China, not Canada, is top US trade partner

Tu first Chinese to win Nobel Prize in Medicine

Huntsman says Sino-US relationship needs common goals

US Weekly

|

|