Cave Buddhas dwell in digital display

Updated: 2012-10-26 10:55

By Kelly Chung Dawson in New York (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

An exhibit at New York University includes this view of the condition of an ancient Buddhist altar inside the south cave at Xiangtangshan, in China's Hebei province. The site was ransacked in the early 20th century by looters who forcibly removed the heads from Buddha figures and sold them and other artifacts. Andrea Brizzi / for China Daily |

|

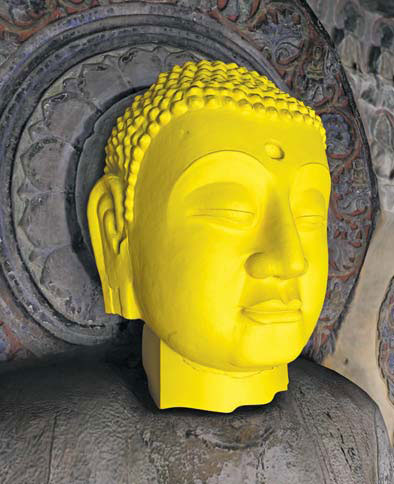

The missing head of a Buddha in a Xiangtangshan cave temple was digitally reconstructed for the New York University exhibit. Andrea Brizzi / for China Daily |

|

Portions of the 1,500-year-old cave temples of Xiangtangshan can be seen, with digital enhancement, at NYU until Jan 6. Andrea Brizzi / for China Daily |

During the brief reign of the Northern Qi dynasty (AD 550-577), part of the chaotic period of the Southern-Northern Dynasties (AD 420-589) that saw Buddhism gain increasing popularity, China's rulers carved elaborate cave temples into the limestone mountains of what is now Xiangtangshan, or "Mountains of Echoing Halls", in southern Hebei province.

Meant to depict paradise, the caves were painted and decorated with detailed images of Buddha and other spiritual figures. Many of those pieces were looted and spirited out of China in the early 20th century, and are now housed in Western institutions.

A new exhibit at New York University attempts a virtual reunification of those objects with their cave origins, using 3-D technology to identify and re-create the placement of the items in their ancient setting.

"It's a beautiful marriage between traditional iconographic studies, stylistic presentations of art and 21st-century digital technology," said Jennifer Chi, exhibitions director at NYU's Institute for the Study of the Ancient World.

"The exhibition traces both traditional representations of art, but also new and innovative ways to add meaning to the overall study of the material."

Echoes of the Past: The Buddhist Cave Temples of Xiangtangshan (on display through Jan 6, 2013) presents a dozen sculptures on loan from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, Britain's Victoria and Albert Museum and other institutions.

The figures include a 3-foot-tall Buddha head dating to AD 550-559, a free-standing figure of a seated Buddha, several bodhisattvas (enlightened beings) and pratyekabuddhas (solitary buddhas), and a number of monsters.

Especially compelling is the show's digital 3-D reconstruction of the interior of one of the seven caves of Xiangtangshan, from which the bulk of treasures on display were excavated.

Visitors stand between three screens, onto which digitized scans of the temple caves are projected, layered with those of the sculptures. The result allows viewers a chance to experience the space as it existed hundreds of years ago.

"It's one of the most innovative and unique displays I've ever seen," said Chi, who is also chief curator of the Xiangtangshan show. "The digital cave features a combination of digital imagery, contemporary photos, archival photographs, and then these 3-D scans.

"I've never seen an exhibition that's attempted to do this in that kind of detailed manner," she said.

The collection was previously shown at the San Diego Museum of Art, the Smithsonian Institution's Arthur M Sackler Gallery in Washington and elsewhere.

Katherine Tsiang, associate director of the Center for the Art of East Asia at the University of Chicago, led the team that initiated the project. Between 2005 and 2008, she and her associates visited museums around the world, using 3-D laser-scanning to document sculptures known to have been taken from the caves at Xiangtangshan.

"Our work is quite new," Tsiang told China Daily. "It is groundbreaking because of the use of 3-D models that can be viewed on the computer to find the original locations of the pieces by matching the traces from the caves with the cuttings on the sculptures. It was very exciting."

The research team worked closely with a group of scholars at Peking University, who used the same technology to scan the interiors of the caves. The results were then stitched together and merged with the scans of the sculptures, to create 3-D models, Tsiang said.

"The exhibition demonstrates what 21st-century techniques and a modern mentality can do to recontextualize sculpture," Chi said.

"These sculptures have always been recognized as extraordinarily beautiful emblems of early iconistic Buddhist style, and have always carried historical cachet."

But the original setting, she said, can teach patrons "a lot more about the meaning and historical context of the sculptures".

For example, by reconstructing the caves in their original configuration, researchers were able to posit that 16 seated Buddhas likely represented northern princes, she said.

There were a number of surprises, Tsiang said. Several pieces surfaced unexpectedly. The head of New York City's Morgan Library and Museum visited the exhibition when it came to the University of Chicago, and recognized a piece from a photo. That sculpture, a Buddha head, had been in the Morgan's reading room since the 1950s, Tsiang said. Another had been stored in a Columbia University library basement for decades; a researcher recognized it while working on the collection.

The exhibition will likely travel to China in some form, Tsiang said. But Western institutions would be hesitant to allow any of the sculptures themselves to cross back into China, she said. The issue of art repatriation has become acute given Turkey's recent call for New York's Met and London's Victoria and Albert Museum to return pieces that may have been looted.

"There is a sensitive aspect to it, because these pieces were removed in the last century, during a period of political disorder," Tsiang said. "There was very little control or supervision of sites during that time of great political upheaval. Today, something like that would never happen because the caves are protected.

"We want people to understand the consequences of looting and collecting art. Buddhist sculptures were originally meant for worship, but in the West in the early part of the 20th century they were bought as art. As a result, many of the sculptures were destroyed or damaged."

Chi believes US audiences will be surprised to learn about lesser-known aspects of Buddhist worship.

"The very fact that Buddhist worship was happening in caves is something that Americans were totally unaware of," she said. "Being able to show the sculptures in their original context, and to re-create the atmosphere of worship at the time, will be truly eye-opening for many people."

kdawson@chinadailyusa.com

(China Daily 10/26/2012 page8)

Relief reaches isolated village

Relief reaches isolated village

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Earth Day marked around the world

Earth Day marked around the world

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Health new priority for quake zone

Xi meets US top military officer

Japan's boats driven out of Diaoyu

China mulls online shopping legislation

Bird flu death toll rises to 22

Putin appoints new ambassador to China

Japanese ships blocked from Diaoyu Islands

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

US Weekly

|

|