Challenging conventional wisdom

|

|

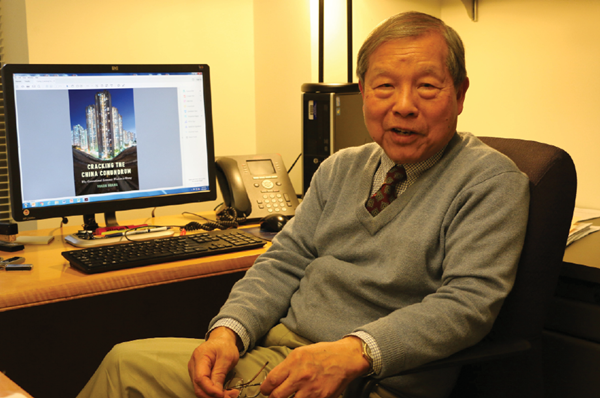

Yukon Huang, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, talks to China Daily in his office. Chen Weihua / China Daily |

Economist Yukon Huang says that many widely held views about China's economy are just plain wrong

In 1949, five-year-old Yukon Huang was sent by his grandfather on a plane from China to join his parents who were then pursuing graduate study in the United States. He did not return to his motherland until 1997, when he was appointed World Bank country director for China.

The economist has since not only worked in China and been studying China, but also owns an apartment in Beijing where he stays during his frequent visits.

Huang, a senior fellow of the Asia program at Washington-based Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, has lately been fighting a battle against what he called the conventional wisdom about the Chinese economy, over issues such as local government debt, trade and investment relations with the United States, corruption and economic development.

Debt, infrastructure

Many economists have sounded the alarm about the huge local government debt in China, yet Huang is less worried. He believes those people have not delved into some unique features of the Chinese system.

In China, local governments are often economic entities. They own land, they build and they operate and generate profits. They compete with companies as well as other local governments.

"When they are operating and competing in a beneficial way with enterprises, China grows extremely well," Huang said. "But when they are not, they can create problems such as overinvestment and environmental degradation."

In China, a lot of the local government debt is borrowed from banks to build roads and other infrastructure projects, a situation that never happens in the US, where infrastructure is always financed by local government budgets or sometimes bonds.

To Huang, the size of China's budget at both the local and central levels is way below the norm. When the high savings of Chinese households under very low interest rates are channeled to State-owned enterprises and local governments to build infrastructure, it "works spectacularly."

He acknowledged that this was like a tax on household saving. However, compared with the sales tax in other countries, Huang believes such a tax on household savings is not regressive. "Essentially, it's a tax that is progressive and hit the rich households more than the poor," he said.

This, according to Huang, is why China is able to finance infrastructure. "Infrastructure construction has been incredible. No other country has done this way," he told China Daily in an interview in his office.

While all the analysis on this is negative because banks are said to lend too much to the local governments who can't repay the loans, Huang called it "a virtue".

To him, it's not really a problem as long as the infrastructure is productive. "Because the economy grows rapidly, so essentially you grow out of this debt," he said.

In China's case, the debt was taken over by the state and absorbed by the government as non-performing loans. "It is saying they would finance it from the budget anyway, but the banks did it for them. Now it's come back," Huang said. He saw this as more of a fiscal deficit and a budget issue rather than a bank problem.

While Western analysis often associated non-performing loans with weak banks, problem banks and debt crisis, Huang said it is actually a very efficient way of growing. "It's actually a good thing. If they had not done this, China could not have grown 10 percent a year for 30 years," he said.

New book

This was just one of the many widely held myths that Huang dispells in his upcoming book Cracking the China Conundrum: Why Conventional Economic Wisdom Is Wrong.

Huang also argues against the conventional wisdom that the US trade deficit is caused by China's trade surplus. He said there is no relationship. "Americans will be very skeptical. Frankly even Chinese were skeptical because they also worry there is a link between China's surplus and America's deficits," Huang said.

By his analysis, the US trade deficits became very large in the late 1990s when the Chinese mainland's trade surplus didn't even exist. Those generating deficits were Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore.

China only accounted for 10 percent of East Asia's trade surplus with the US in 1997. But that grew to 70 percent four years ago, when many assembly lines had been relocated to the Chinese mainland. However, the total trade surplus of Asia with the US didn't change at all, according to Huang.

He argues that the bilateral trade deficit does not matter, and a trade deficit is not directly related to the health of the economy and employment. The US has been running trade deficits for more than 40 years, during periods of both full employment and massive unemployment and during times of both good economic performance and bad performance.

There is no doubt to him that the perpetual trade deficit generated by the US is due to the role of the US dollar as a global reserve currency. "The only way they (foreigners) can hold it is if the US has a trade deficit," he said.

Huang believes the unique US dollar role also means it's perpetually overvalued. It means exports are basically repressed and imports are encouraged. "This is not a China issue. It's not a German issue, not a Mexico issue," he said.

"The only way to get rid of the trade deficit is to eliminate the US dollar as the global currency," Huang teased. He believes that if people understand this, the discussion of policies will be on a sound analytical footing. "Right, it is not at all," he said.

He was surprised that US Commerce Department officials he talked to were not quite aware of the top US exports to China. While some get it right for the top two categories (agricultural products and Boeing airplanes), few know the third-largest category (recycled cardboards and tin cans) and the fourth-largest category (cars, mostly SUVs).

"If you don't know the pattern of trade, how can you formulate policy?" Huang asked.

China experience

Born in Chengdu of southwest China's Sichuan province, Huang grew up with his grandfather in Changsha, central China's Hunan province.

Coming to the US in 1949, he attended elementary school and high school in Washington. It was totally unlike today and there were very few Chinese students at the time. In fact, he was the only Chinese in his high school of 600 students. (Today that school is 20 percent Chinese.)

The situation was pretty much similar when he went to Yale University for his undergraduate study in the early 1960s, there weren't many Chinese either. Huang said he did not get to speak Chinese much in those years.

After earning a doctorate in economics at Princeton University in 1971, Huang taught at University of Virginia for six years before working briefly for the US Treasury Department in the mid '70s.

He later joined the World Bank, working and living in countries such as Bangladesh, Malaysia and Russia. Huang said working in both market and transitional economies has helped him better understand China's situation.

He ended up living in China for seven years after becoming the World Bank country director there from 1997 to 2004. It also allowed him to travel in all the 30 provinces and municipalities to visit World Bank projects there.

Huang described the relationship between the World Bank and China as generally very good. He said China is a "very good client."

While some of China's views are valid and some not, Huang said it always works out properly. "It has been pretty positive between the World Bank and China for the last three decades," he said.