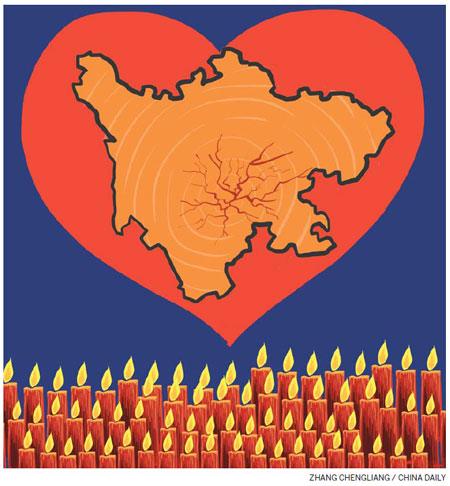

Lessons from an earthquake

Updated: 2013-04-26 09:06

By Giles Chance (China Daily)

|

||||||||

Ya'an disaster points to a change in the Chinese public's mood

The earthquake in Ya'an in western Sichuan province on April 20 with a magnitude of 7 was the second major seismic event to occur in China - the other being the Yushu quake in Qinghai province in 2010 - since the Wenchuan earthquake of May 12, 2008. The Wenchuan earthquake was bigger, at a magnitude of 8, and killed more than 80,000 people and injured 375,000; In Ya'an about 200 are dead, and more than 12,000 injured. Does this show that the earthquake emergency services in Sichuan have become more efficient than they were in 2008?

The response in Ya'an by the emergency services showed that lessons have been learned from 2008, but this was probably not the main reason for the fewer deaths. Earthquakes are measured on a logarithmic, not an arithmetic scale. So the Ya'an earthquake, measured at 7, was 10 times less powerful than the Wenchuan earthquake, and generated 30 times less energy. This must be the major reason for the difference in destruction.

Also, the earthquake happened at a more convenient time, 8 am, when people were out of bed and able to react, but before children had gone to school. In 2008 in Wenchuan many casualties were caused by collapsing school buildings that crushed students already in their classrooms.

China sits on the junction of two tectonic plates and is one of the world's major earthquake zones. Most of the large earthquakes that have happened in China in the last 100 years have occurred in Sichuan, where the Sichuan plain meets the Tibetan mountains to create a significant crack in the earth's crust, called the Longmenshan Fault. That runs southwest to northeast between 30 and 34 degrees north and 103 to 106 degrees east. Wenchuan (31 degrees north, 103 degrees east and 92 kilometers northwest of Chengdu) and Ya'an (30 degrees north, 102 degrees east and 116 kilometers southwest of Chengdu) both lie on the Longmenshan Fault.

Since 2000 there have been four earthquakes, all of magnitude 6 or larger, along or close to the Longmenshan Fault.

The response to the Ya'an earthquake demonstrated a new and increasingly important feature of Chinese society: The prevalence and power of social media, whether in the hands of the authorities or of the public. The earthquake struck at 8:02 am. At 08:29 the China International Rescue Team posted a microblog on Weibo that gave details of the earthquake and asked those affected to report what they saw and whether they had been hurt.

The microblog was forwarded more than 400,000 times and received more than 37,000 responses. A picture taken of the earthquake site that morning and posted on Netease received more than 10 million page views. Another weibo blog shortly after the earthquake read: "Sichuan Ya'an earthquake, everyone please forward this on. Everyone give way on the Chengdu-Ya'an highway. Leave a path for the rescue, hospital, and military vehicles, the golden 72 hours (critical time after a disaster). Time is life. Also, communications to Ya'an Lushan county are currently down, so please for the moment don't continuously redial Sichuan telephone numbers. Everyone please use microblogs and text messages instead for communications, leaving precious communications resources to save lives. Please spread this."

The public used weibo to criticize public donations for earthquake relief, a suspicion being that not all donated funds would reach the needy. Clearly, the scandal of Guo Meimei, a young woman who boasted in 2011 that she had used Red Cross funds to support her luxurious lifestyle, has had a significant impact on the public perception of the management of public charities in China.

In Hong Kong, more than 90 percent of people surveyed supported a call by Leung Chun-ying, the chief executive, for an earthquake gift of HK$100 million ($12 million; 9.9 million euros) but on condition that it should be carefully monitored and controlled to ensure it ended up in the right place.

In 2008 when the Wenchuan earthquake occurred, China's social media was not yet a significant force. But the response to the Ya'an earthquake shows how weibo and other Chinese social media, in the five years since 2008, have become a powerful force for allowing the public to be kept informed, as well as to express opinions.

The explosion at the Boston Marathon in the United States on April 16, and the manhunt that followed created world news. But the Ya'an earthquake four days later, in which many more people died and were injured, received comparatively little attention in most Western media. Can the world only deal with one major catastrophe at a time?

The Wenchuan earthquake sparked a wave of compassionate giving from the Chinese public. More than $1.5 billion (1.1 billion euros) was contributed to support relief and reconstruction efforts. The donations of celebrities were conspicuous, Yao Ming alone contributing more than $300,000. The latest earthquake, admittedly with a much smaller number of deaths, has not induced anything like 2008's wave of public sympathy. Instead there has been an outpouring of public skepticism about the fate of donations. It seems that the Chinese public's mood has changed significantly since 2008. The public response to the Ya'an earthquake shows a Chinese public with its own mind, one that is patriotic and public-spirited, yet increasingly intolerant of official misbehavior and incompetence. This development, a kind of political maturing, will support the increases in government transparency and competence that the new president is determined to strengthen.

In the aftermath of the Ya'an earthquake, many Chinese compared Japanese building standards to those in Sichuan. No doubt many more earthquakes will occur along the Longmenshan Fault in western Sichuan. Let us hope that the local authorities start to upgrade building standards so the number of deaths and injuries that will otherwise undoubtedly occur is reduced.

The author is a visiting professor at Guanghua School of Management, Peking University. The views do not necessarily reflect those of China Daily.

(China Daily 04/26/2013 page9)

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

No let up in home price rises

Bird-watchers undaunted by H7N9 virus

Onset of flood season adds to quake zone risks

Vice-president Li meets US diplomat

China has a tourism law

Meeting delivers big deals

China denies border spat with India

Chinese consumers push US exports higher

US Weekly

|

|