Weary crew fights to save stranded US dolphins

Updated: 2012-02-18 09:17

(China Daily)

|

||||||||

WELLFLEET, Massachusetts - There's no good spot on Cape Cod for dolphins to beach themselves, but on this cold, gray day a group of 11 has chosen one of the worst.

The remote inlet down Wellfleet's Herring River is a place where the tides recede fast and far, and that's left the animals mired in a grayish-brown mud one local calls "Wellfleet mayonnaise".

|

|

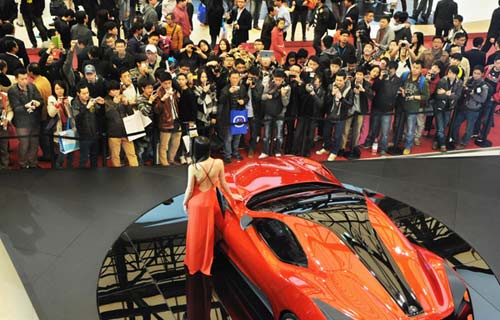

Katie Moore, an International Fund for Animal Welfare rescue team member, approaches a portion of a pod of 11 dolphins stranded on a mud flat during low tide in Wellfl eet, Massachusetts, on Tuesday. Ten of the dolphins were saved and one perished during the event. There have been 177 dolphins stranded in the area since Jan 12, and 53 have been successfully released. [Photo/Agencies] |

Walking is the only way to reach the animals, but it's not easy. Rescuers crunch through cord grass and seashells before hitting a grabby muck that releases footsteps with a sucking pop. One volunteer hits a thigh-deep hole and tumbles forward. Mud covers his face like messy war paint.

It's a scene that's played itself out all winter long, and scientists have no idea why. A year ago, the 11 dolphins that stranded themselves on Tuesday would have been a remarkable number. Now they're just added to an ever-growing tally.

In the last month, 178 short-beaked common dolphins have stranded on Cape Cod, and 125 have died. The total is nearly five times the average of 37 common dolphins that have stranded each of the past 12 years.

Workers at the International Fund for Animal Welfare, which has led the rescue efforts, tag and take blood from the stranded animals. Necropsies have been done on dead dolphins, and a Congressional briefing was held this month in the push for answers. But researchers can offer only theories such as changes in weather, water temperature or behavior of the dolphins' prey.

Geography may also play a role, if the dolphins are getting lost along the Cape's jagged inner coastline in towns such as Wellfleet.

In mid-February, Wellfleet feels like a place long emptied out after a dimly remembered party. A drive into town takes you past a closed mini-golf course, candy store and drive-in theater. A downtown road rolls by shuttered cottages and motel cabins.

But Wellfleet is a hot spot for the dolphin strandings, in part because of features such as Jeremy Point, a thin peninsula that blocks the way to Cape Cod Bay if the dolphins wander too far into the town's harbor, as they did on Tuesday.

The rescuers make a quick assessment once they reach the 11 animals.

One dolphin is dead, but the other 10 appear healthy, and some bang their tails in the shallows, struggling to move. Rescuers decide the best course is to wait for the incoming tide to free the dolphins so boats can try to herd them out of trouble. The only other alternative is hauling them to a waiting trailer, and open water. But the trailer is more than a kilometer away.

Waiting has risks. Dolphins can't survive long on land, and there's no guarantee the boats can push the dolphins on to safety.

"Now's where we start crossing our fingers," says the fund's Brian Sharp as he heads for a boat.

Rescuers in orange vests and black waders work in pairs to move the dolphins on slings, bringing them closer together and keeping them pointed the right way.

"We'll take advantage of the fact that they're social animals," says Kerry Branon, a fund spokeswoman. "We're hoping if we release them together, they'll stick together and then we'll herd them out around the point."

Not all the dolphins are on board with the plan, though. One drifts off to the left, where he could beach again.

The manager of the stranding team, Katie Moore, slides over, grabs its dorsal fin and gives it a push in the right direction.

"You're going the wrong way, buddy," she says.

The inlet continues to fill and the dolphins break into waters that are deeper than the rescuers can follow, but they're separated into two groups. The IFAW's boat eventually follows one pod and the Wellfleet harbormaster takes another. The noise from the motors pushes the dolphins ahead. So do acoustic pingers, which make a sound that annoys the dolphins.

From here, all the shore workers can do is await word from the boats, which will follow the dolphins until dark, if needed. The crew trudges off the beach and gathers later in a parking lot at the Wellfleet marina, where coffee and doughnut holes beckon.

Associated Press

Relief reaches isolated village

Relief reaches isolated village

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Earth Day marked around the world

Earth Day marked around the world

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Health new priority for quake zone

Xi meets US top military officer

Japan's boats driven out of Diaoyu

China mulls online shopping legislation

Bird flu death toll rises to 22

Putin appoints new ambassador to China

Japanese ships blocked from Diaoyu Islands

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

US Weekly

|

|