NY Times journalists digest Mandarin with lunch

Updated: 2012-03-03 07:51

By Kelly Chung Dawson (China Daily)

|

||||||||

NEW YORK - Like most major news organizations today, The New York Times employs full-time journalists reporting from China.

While The Times' overseas correspondents complete intensive Chinese language training to report effectively, its employees based in New York also have the opportunity to study Mandarin in weekly in-office classes during lunch.

|

|

|

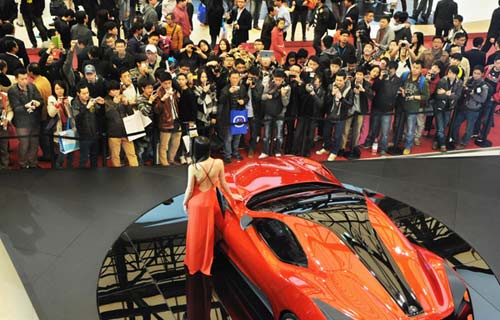

Pen-Pen Chen (center), who teaches Chinese at the New York Times office, gives instructions to Valerie Lodi (left) and Mary Walsh. Wang Chao / China Daily |

Initiated in 2009 by the newspaper's Asian Heritage Network (one of seven employee-led affinity groups), the courses are offered at the beginning and intermediate/advanced levels in three semesters, with each class averaging around 10 students each semester, according to organizers.

"Our goal was to increase cultural awareness with respect to Asian culture," said Thomas Lin, a senior producer with the newspaper's science desk, and a member of the steering committee for the Asian Heritage Network.

"In general you want more diversity within the newsroom. But particularly when someone is writing about the Asian community, it's better that the person understands and is sensitive to the culture. To know more about a language is to know more about the culture, and that's why we wanted to create this program."

Desiree Dancy, chief diversity officer and VP of corporate human resources at the Times, said that the courses are offered as an opportunity for employees to understand different communities.

"It's really designed to enhance the learning environment and learning culture," Dancy said in an interview with China Daily. "On some level, as we go out into different markets, and are reporting on different communities, it's absolutely valuable for employees to speak Mandarin."

Although Mandarin is gaining in popularity for language study in the United States, it is uncommon for news organizations to offer language courses to their employees, Dancy said. She believes The New York Times is one of the only publications that does so.

For a number of journalists enrolled in the courses, the practical knowledge gained from studying Mandarin has been directly useful to their work. Mary Walsh, who writes about financial topics including debt, said that she began taking the courses because the US-China economic relationship has become increasingly important.

"If China is growing fast and making our products, it's good to understand what's going on there," Walsh said.

"If inflation changes, and if monetary policy changes, it'll start to feed into how policy is made in this country. I don't know why or how exactly, but I know it will be good for me to speak Chinese. The China-US relationship is an important one, and I write about these things, so it just seems like at some point I'm going to use this."

Pia Chon, a beginning student who works in marketing at The Times, said that she is also studying Mandarin for practical purposes.

"I think that the three languages of the future are Arabic for politics, English as a universal language, and Mandarin from a commerce perspective," she said in an interview with China Daily.

"Living in Manhattan, our viewpoint might be a bit skewed, but on a general level I do think that wherever you are located in the US, there is no doubt the importance of China as a country is emerging. I think Chinese will be the language of commerce, and an important language to have from a business perspective."

In order for journalists to accurately cover less mainstream communities, a deeper understanding of their culture is necessary, Lin said.

"I think that for a news report to not only be accurate but in some basic sense understand the context of where the people are from and what their concerns are, the more the reporters are immersed in that culture the more they can be sensitive to the nuances of a particular culture," Lin said.

"It's of great value to us as journalists to learn as much as we can about other cultures."

Other students say they are taking the courses simply because the subsidized costs ($10 per class) and the convenience of location are too good to pass up. The courses have been designed to focus not only on language but on culture, Lin said.

Pen-Pen Chen, who teaches the course, said that although some Mandarin teachers prefer to focus purely on language, she also teaches cultural components.

"Some teachers think that's a big taboo, but I think that language and culture are so intertwined that it's important to teach with cultural context," she said. There is a lack of textbooks currently available for adults, so she designs the curriculum herself, she said.

Relief reaches isolated village

Relief reaches isolated village

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Earth Day marked around the world

Earth Day marked around the world

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Health new priority for quake zone

Xi meets US top military officer

Japan's boats driven out of Diaoyu

China mulls online shopping legislation

Bird flu death toll rises to 22

Putin appoints new ambassador to China

Japanese ships blocked from Diaoyu Islands

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

US Weekly

|

|