Seeking clues to the universe

Updated: 2012-04-22 07:34

By Simon Romero (The New York Times)

|

||||||||

|

There will be 66 radio antennas in use at the ALMA site in Chile's Atacama Desert when the project is completed next year. [Tomas Munita for The New York Times] |

In Chile's desert, building a huge astronomical array

LLANO DE CHAJNANTOR, Chile - Trucks stall on the road to this plateau 5,058 meters up in the Atacama Desert, where scientists are installing one of the world's largest ground-based astronomical projects. Heads ache. Noses bleed. Dizziness overcomes the researchers toiling in the shadow of the Licancabur volcano.

"Then there's what we call 'jelly legs,'" said Diego Garcia-Appadoo, a Spanish astronomer. "You feel shattered, as if you ran a marathon."

Still, the same conditions that make the Atacama, Earth's driest desert, so inhospitable make it beguiling for astronomy. In northern Chile, it is far from big cities, with little light pollution. Its arid climate prevents radio signals from being absorbed by water droplets. The altitude, as high as the Himalaya base camps for climbers preparing to scale Mount Everest, places astronomers closer to the heavens.

The array's construction, said Jesus Mosterin, a prominent Spanish philosopher who writes about the frontier between science and philosophy, and who visited the observatory last year, is taking place at "the only time in history that windows into the universe are being thrown wide open."

Chile is not the only country luring big investments in astronomical projects. South Africa and Australia are competing to host an even bigger radio telescope, the Square Kilometer Array, which would be fully operational by 2024. China has begun building its own large radio telescope in a craterlike setting in the southern province of Guizhou.

The Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array, known as ALMA, which opened in October, will have spread 66 radio antennas near the spine of the Andes by the time it is completed next year. Drawing more than $1 billion in funding mainly from the United States, European countries and Japan, ALMA will help the oxygen-deprived scientists who are flocking to this region to study the origins of the universe.

The project also strengthens Chile's position in the vanguard of astronomy. Observatories are already scattered throughout the Atacama, including the Cerro Paranal Observatory, where scientists discovered in 2010 the largest star observed to date.

The ALMA project opens a new stage for astronomy in Chile, which is favored by international research organizations for the stability of its economy and legal system. Like other radio telescopes, the array does not detect optical light but radio waves, allowing researchers to study parts of the universe that are dark, like the clouds of cold gas from which stars are formed.

With the array, astronomers hope to see where the first galaxies were formed, and perhaps even detect solar systems with the conditions to support life. But the scientists here express caution about their chances of finding life elsewhere in the universe, explaining that such definitive proof is likely to remain elusive.

"We won't be able to see life, but perhaps signatures of life," said Thijs de Graauw, a Dutch astronomer who is the project's director.

Still, scientists believe the array will make transformational leaps possible in the understanding of the universe, enabling a hunt for so-called cold gas tracers, the ashes of exploded stars from a time about a few hundred million years after the Big Bang that astronomers call "cosmic dawn."

At ALMA, a sense of awe still accompanies the installation of each antenna. Two giant German-manufactured transporters, each with 28 tires and engines equivalent to two Formula 1 racing vehicles, are used to transport the antennas. Called Otto and Lore, they look like massive mechanized centipedes making their way across the arid landscape.

But the financial crisis in rich industrialized countries has raised concerns that funding for some ambitious astronomy projects could face constraints.

"It would be very sad for humankind if we were so spiritually decadent to forgo the pleasures of consciousness and of knowledge," said Mr. Mosterin. "These things make human beings a very interesting animal indeed."

The New York Times

|

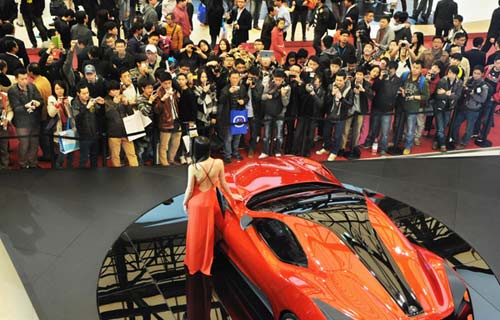

Antennas dot the desert in Atacama, which has a dry climate and little light pollution, ideal conditions for astronomical research. [Tomas Munita for The New York Times]

|

Relief reaches isolated village

Relief reaches isolated village

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Earth Day marked around the world

Earth Day marked around the world

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Health new priority for quake zone

Xi meets US top military officer

Japan's boats driven out of Diaoyu

China mulls online shopping legislation

Bird flu death toll rises to 22

Putin appoints new ambassador to China

Japanese ships blocked from Diaoyu Islands

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

US Weekly

|

|