Japan's homeless recruited for murky Fukushima clean-up

Updated: 2013-12-30 09:37

(Agencies)

|

||||||||

'DON'T ASK QUESTIONS'

Japan has always had a gray market of day labor centered in Tokyo and Osaka. A small army of day laborers was employed to build the stadiums and parks for the 1964 Olympics in Tokyo. But over the past year, Sendai, the biggest city in the disaster zone, has emerged as a hiring hub for homeless men. Many work clearing rubble left behind by the 2011 tsunami and cleaning up radioactive hotspots by removing topsoil, cutting grass and scrubbing down houses around the destroyed nuclear plant, workers and city officials say.

Seiji Sasa, 67, a broad-shouldered former wrestling promoter, was photographed by undercover police recruiting homeless men at the Sendai train station to work in the nuclear cleanup. The workers were then handed off through a chain of companies reporting up to Obayashi, as part of a $1.4 million contract to decontaminate roads in Fukushima, police say.

"I don't ask questions; that's not my job," Sasa said in an interview with Reuters. "I just find people and send them to work. I send them and get money in exchange. That's it. I don't get involved in what happens after that."

Only a third of the money allocated for wages by Obayashi's top contractor made it to the workers Sasa had found. The rest was skimmed by middlemen, police say. After deductions for food and lodging, that left workers with an hourly rate of about $6, just below the minimum wage equal to about $6.50 per hour in Fukushima, according to wage data provided by police. Some of the homeless men ended up in debt after fees for food and housing were deducted, police say.

Sasa was arrested in November and released without being charged. Police were after his client, Mitsunori Nishimura, a local Inagawa-kai gangster. Nishimura housed workers in cramped dorms on the edge of Sendai and skimmed an estimated $10,000 of public funding intended for their wages each month, police say.

Nishimura, who could not be reached for comment, was arrested and paid a $2,500 fine. Nishimura is widely known in Sendai. Seiryu Home, a shelter funded by the city, had sent other homeless men to work for him on recovery jobs after the 2011 disaster.

"He seemed like such a nice guy," said Yota Iozawa, a shelter manager. "It was bad luck. I can't investigate everything about every company."

In the incident that prompted his arrest, Nishimura placed his workers with Shinei Clean, a company with about 15 employees based on a winding farm road south of Sendai. Police turned up there to arrest Shinei's president, Toshiaki Osada, after a search of his office, according to Tatsuya Shoji, who is both Osada's nephew and a company manager. Shinei had sent dump trucks to sort debris from the disaster. "Everyone is involved in sending workers," said Shoji. "I guess we just happened to get caught this time."

Osada, who could not be reached for comment, was fined about $5,000. Shinei was also fined about $5,000.

'RUN BY GANGS'

The trail from Shinei led police to a slightly larger neighboring company with about 30 employees, Fujisai Couken. Fujisai says it was under pressure from a larger contractor, Raito Kogyo, to provide workers for Fukushima. Kenichi Sayama, Fujisai's general manger, said his company only made about $10 per day per worker it outsourced. When the job appeared to be going too slowly, Fujisai asked Shinei for more help and they turned to Nishimura.

A Fujisai manager, Fuminori Hayashi, was arrested and paid a $5,000 fine, police said. Fujisai also paid a $5,000 fine.

"If you don't get involved (with gangs), you're not going to get enough workers," said Sayama, Fujisai's general manager. "The construction industry is 90 percent run by gangs."

Raito Kogyo, a top-tier subcontractor to Obayashi, has about 300 workers in decontamination projects around Fukushima and owns subsidiaries in both Japan and the United States. Raito agreed that the project faced a shortage of workers but said it had been deceived. Raito said it was unaware of a shadow contractor under Fujisai tied to organized crime.

"We can only check on lower-tier subcontractors if they are honest with us," said Tomoyuki Yamane, head of marketing for Raito. Raito and Obayashi were not accused of any wrongdoing and were not penalized.

Other firms receiving government contracts in the decontamination zone have hired homeless men from Sasa, including Shuto Kogyo, a firm based in Himeji, western Japan.

"He sends people in, but they don't stick around for long," said Fujiko Kaneda, 70, who runs Shuto with her son, Seiki Shuto. "He gathers people in front of the station and sends them to our dorm."

Kaneda invested about $600,000 to cash in on the reconstruction boom. Shuto converted an abandoned roadhouse north of Sendai into a dorm to house workers on reconstruction jobs such as clearing tsunami debris. The company also won two contracts awarded by the Ministry of Environment to clean up two of the most heavily contaminated townships.

Kaneda had been arrested in 2009 along with her son, Seiki, for charging illegally high interest rates on loans to pensioners. Kaneda signed an admission of guilt for police, a document she says she did not understand, and paid a fine of $8,000. Seiki was given a sentence of two years prison time suspended for four years and paid a $20,000 fine, according to police. Seiki declined to comment.

UNPAID WAGE CLAIMS

In Fukushima, Shuto has faced at least two claims with local labor regulators over unpaid wages, according to Kaneda. In a separate case, a 55-year-old homeless man reported being paid the equivalent of $10 for a full month of work at Shuto. The worker's paystub, reviewed by Reuters, showed charges for food, accommodation and laundry were docked from his monthly pay equivalent to about $1,500, leaving him with $10 at the end of the August.

The man turned up broke and homeless at Sendai Station in October after working for Shuto, but disappeared soon afterwards, according to Yasuhiro Aoki, a Baptist pastor and homeless advocate.

Kaneda confirmed the man had worked for her but said she treats her workers fairly. She said Shuto Kogyo pays workers at least $80 for a day's work while docking the equivalent of $35 for food. Many of her workers end up borrowing from her to make ends meet, she said. One of them had owed her $20,000 before beginning work in Fukushima, she says. The balance has come down recently, but then he borrowed another $2,000 for the year-end holidays.

"He will never be able to pay me back," she said.

The problem of workers running themselves into debt is widespread. "Many homeless people are just put into dormitories, and the fees for lodging and food are automatically docked from their wages," said Aoki, the pastor. "Then at the end of the month, they're left with no pay at all."

Shizuya Nishiyama, 57, says he briefly worked for Shuto clearing rubble. He now sleeps on a cardboard box in Sendai Station. He says he left after a dispute over wages, one of several he has had with construction firms, including two handling decontamination jobs.

Nishiyama's first employer in Sendai offered him $90 a day for his first job clearing tsunami debris. But he was made to pay as much as $50 a day for food and lodging. He also was not paid on the days he was unable to work. On those days, though, he would still be charged for room and board. He decided he was better off living on the street than going into debt.

"We're an easy target for recruiters," Nishiyama said. "We turn up here with all our bags, wheeling them around and we're easy to spot. They say to us, are you looking for work? Are you hungry? And if we haven't eaten, they offer to find us a job."

Second blast kills 10 in Russian city

Second blast kills 10 in Russian city

F1 legend Schumacher in coma after ski accident

F1 legend Schumacher in coma after ski accident

Net result

Net result

Fire on express train in India kills at least 26

Fire on express train in India kills at least 26

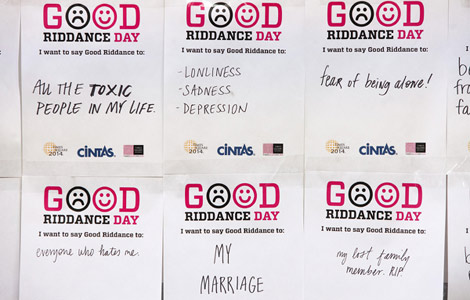

Times Square visitors purge bad memories

Times Square visitors purge bad memories

Ice storm leaves many without power in US, Canada

Ice storm leaves many without power in US, Canada

'Chunyun' train tickets up for sale

'Chunyun' train tickets up for sale

Abe's war shrine visit sparks protest

Abe's war shrine visit sparks protest

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Outrage still festers over Abe shrine visit

Suicide bomber kills 16 at Russian train station

Magazine reveals NSA hacking tactics

Pentagon chief concerned over Egypt

Broader auto future for China, US

Li says economy stable in 2014

Bigger role considered in the Arctic

3rd high-level official probed

US Weekly

|

|