They fought on two fronts

Updated: 2016-01-10 23:25

By Hatty Liu(China Daily Canada)

|

||||||||

|

|

Neill Chan (right) with his fellow soldiers in Force 136 during basic training in India in 1945. COURTESY OF CHINESE CANADIAN MILITARY MUSEUM |

In her book, The Dragon and the Maple Leaf, Wong noted that the SOE asked to recruit a greater number of Chinese Canadians than were voluntarily enlisted in the Canadian Army. The National Defence Department pessimistically believed it could not call up even 150 men for the SOE to recruit.

In the summer of 1944, the Cabinet War Committee finally permitted Chinese Canadians to be called up for active service. After 1942, draftees called under the NRMA had the choice of serving in the home defence or to go overseas. The majority of Chinese draftees who chose to go overseas were loaned to the SOE in Southeast Asia and the Pacific, which operated under the code name Force 136.

Their bilingualism made them suited to interpretation and communication tasks. If necessary, their appearance and their Chinese-language skills also made them ideal candidates for training local resistance fighters in Malaysia and Burma and operating behind enemy lines.

"We were supposed to be on a secret mission," Tommy Wong said. "We would have to parachute into Burma during the night and meet up with the local Chinese, since we could communicate with them, and train and organize the local people in how to resist the Japanese advancement."

The SOE was a secret organization formed by the British Ministry of Economic Warfare in July 1940. Its initial purpose was to assist in the training and arming of resistance movements in occupied parts of Europe after the British Expeditionary Force was driven out of the European Continent.

The SOE in Southeast Asia went under the code name Force 136. Its purpose was to help the resistance in occupied parts of Malaysia, Burma and China itself. Basic training for the Canadian recruits took place in Canada, Britain, Australia and India.

According to Marjorie Wong, few people knew during or after the war what the SOE's purpose was. Most of its members were only aware of their own part in it. The tasks that its members performed were eclectic and varied across regions and situations.

The Canadian media were told not to give publicity to the SOE's recruits, and there would be no disclosure made as to what these Chinese Canadians were being trained or employed in, though they could publish stories about Chinese-Canadian soldiers employed in other areas of the military.

When the war ended in August 1945, Chan and Wong were based in the bush north of Calcutta waiting for their missions to start.

Going overseas

The initial request for Canada to "loan" Chinese soldiers to the SOE in India and Australia referred to the recruits as "wireless operators". Later requests were for men who could be trained as wireless operators, interpreters, translators, liaisons, propaganda operatives and members of "Jedburgh teams", who would be parachuted behind enemy lines to perform sabotage and guerrilla warfare.

Chan was recruited into Force 136 to interpret military communications for the Indian National Army. In addition to being a native Chinese speaker, he had learned Japanese from friends at Vancouver's Strathcona Elementary School, even taking jiu-jitsu lessons in Japantown.

Wong was part of another group that trained to become guerrillas. Chan participated in the same training when he discovered there wasn't a need for more interpreters. There was a long list they had to learn and pass on to the local resistance.

Besides parachuting, getting in touch with the local Chinese and organizing resistance movements, the recruits "had to learn Morse code, how to blow up bridges and demolitions", Wong said. "We learned how to telegraph, how to handle explosives, how to use knives and hand-to-hand combat.

- Obama says US must act on gun violence, defends new gun control rules

- Over 1 million refugees have fled to Europe by sea in 2015: UN

- Turbulence injures multiple Air Canada passengers, diverts flight

- NASA releases stunning images of our planet from space station

- US-led air strikes kill IS leaders linked to Paris attacks

- DPRK senior party official Kim Yang Gon killed in car accident

Special report: Rise and rise of China's outbound tourism

Special report: Rise and rise of China's outbound tourism

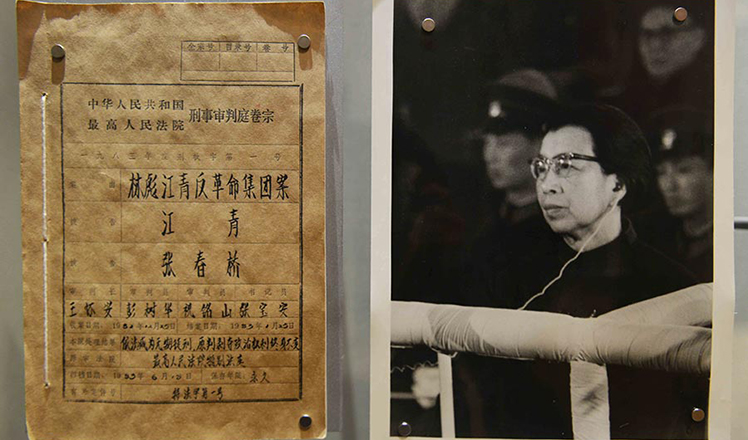

Trial data of former senior Party officials on display

Trial data of former senior Party officials on display

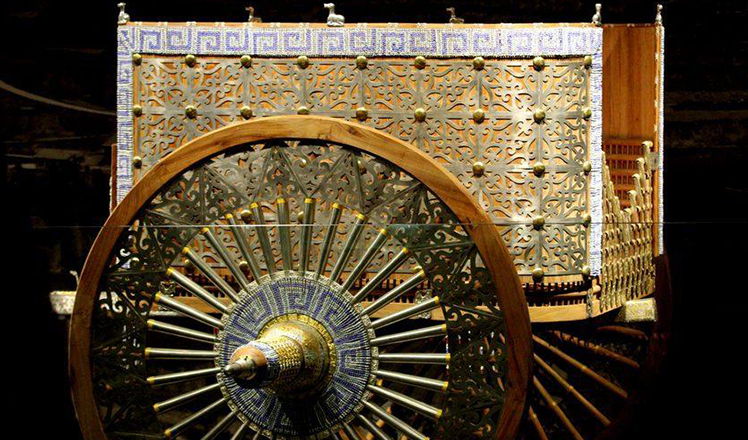

Replica of luxurious chariot from ancient times wows Xi'an visitors

Replica of luxurious chariot from ancient times wows Xi'an visitors

Number of giant pandas in China reaches 422

Number of giant pandas in China reaches 422

Attendees feel the thrill of tech at CES trade show

Attendees feel the thrill of tech at CES trade show

Vivid dough sculptures welcome Year of the Monkey

Vivid dough sculptures welcome Year of the Monkey

Kidnapped five-year-old reunites with her family 56 hours later

Kidnapped five-year-old reunites with her family 56 hours later

Kung Fu Panda hones skills from master

Kung Fu Panda hones skills from master

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Shooting rampage at US social services agency leaves 14 dead

Chinese bargain hunters are changing the retail game

Chinese president arrives in Turkey for G20 summit

Islamic State claims responsibility for Paris attacks

Obama, Netanyahu at White House seek to mend US-Israel ties

China, not Canada, is top US trade partner

Tu first Chinese to win Nobel Prize in Medicine

Huntsman says Sino-US relationship needs common goals

US Weekly

|

|