Trading strategy

The notification last June of a trade deal between Mongolia and Japan was significant. As of that moment, every member of the World Trade Organization had some kind of regional trade agreement in place.

But the push to make global trade easier is now in jeopardy. Trade growth, which has typically been larger than economic growth, slowed significantly last year.

For Asia and its trade-focused economies, this slowdown could require a change of strategy and much greater focus on regional trade to facilitate growth.

Since the turn of the century, global economies have rolled out policies to open trade. However, now the trend is reversing.

"Trade is an important factor but not the only factor," said Jayant Menon, chief economist at the Asian Development Bank. "The developed markets of North America and Europe will continue to be important. However, they are diminishing slowly because they are not growing as fast as Asia or Africa."

Since the 1990s, the push for freer trade has been visible worldwide. Indeed, the dramatic growth experienced by Asian economies is largely thanks to more seamless trade. Export-oriented policies were set throughout the region to grow economies into some of the world's richest.

China leveraged world-class manufacturing capabilities and foreign trade into perhaps the largest and longest economic boom in history. Emerging economies like Vietnam and Cambodia now aim to replicate that trajectory.

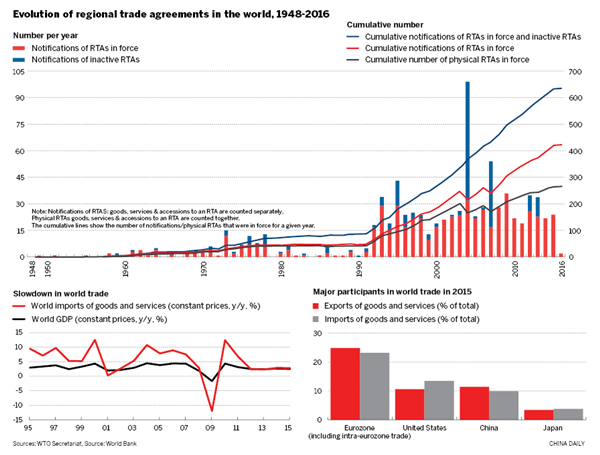

Between 1948 and 1994, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, the earlier iteration of the WTO, received 124 regional trade deal notifications mostly dealing with the trade in goods.

In the 20 years that followed, the WTO received notifications on more than 400 agreements on the trade of goods and services, more than three times as many in less than half the time.

Since 1995, when the WTO was created to replace GATT, trade has generally become easier. Agreements have proliferated, barriers have come down and tariffs generally dropped.

The easier flow of goods and services ensured international trade grew much faster than the global economy over the past decade and a half. Countries typically import what they need and export extra resources, manufactured goods, services and labor. And because a lag exists, trade grows faster than the economies it serves.

In Asia, China established trade deals with countries across the region. The 10-member Association of Southeast Asian Nations launched an economic community that aims to make trade seamless.

But the push toward more globalization now appears to be reversing and, as it does, global trade is slowing below the rate of economic growth.

"The dramatic slowing of trade growth is serious and should serve as a wake-up call," said Roberto Azevedo, director-general of the WTO, in September last year. "It is particularly concerning in the context of growing anti-globalization sentiment."

His fear was that the slowdown would "translate into misguided policies that could make the situation much worse".

Azevedo's comments came as the WTO cut its expectation for 2016 global trade growth from 2.8 percent to 1.7 percent. The revised figure marked the slowest anticipated rate of growth for international trade since the global financial crisis of 2009.

According to the World Bank, the global economy grew by 2.3 percent last year, faster than the anticipated WTO rate.

The WTO expects trade in 2017 to grow between 1.8 percent and 3.1 percent. However, this expectation came before Donald Trump was elected president of the United States, and the rapid rise of protectionist measures in parts of Latin America and Europe.

The WTO also pointed out that its members put in place 2,978 trade-restrictive measures since 2008, and the number jumped 17 percent in the year to October 2016, a number the WTO said "remains worryingly high".

This protectionist push has been balanced out by a recovery in some areas, such as commodities. There has been a broad-based recovery in the prices of oil, palm oil, coal, copper and various metals.

Countries such as South Korea, Japan and Singapore have struggled more as they are focused on the trade of industrial products.

"Starting last year, Southeast Asia has been doing better," said Alaistair Chan, an economist at Moody's Analytics, citing recovering commodity prices as beneficial to the region.

"A lot of the more trade-oriented areas have been struggling somewhat," Chan said.

Singapore is among those feeling the pressure. The large re-export center is usually a good bellwether of the state of global trade. The city-state's exports dropped last year, the fourth year in a row. However, exports of domestically produced goods strengthened toward the end of 2016.

"It's hard to draw a conclusion on Singapore's domestic economy based on how Singapore's exports are doing. Basically, it re-exports," said Chan.

Francis Tan, an economist at United Overseas Bank, said the bank is "carefully watching the negative impact from the anti-globalization rhetoric that has been fueling developed markets' sentiment".

This is particularly true of the US, where exports of goods fell 3 percent throughout 2016 to $1.45 trillion and a trade deficit of 1.5 percent or $734.3 billion. But that is not the whole story.

The US continues to log large surpluses in the trade of services, an area in which Asia lags. The surplus in services trade hit $247.8 billion in 2016. Official US Department of Commerce figures put its 2016 trade deficit at $502.3 billion.

Still, the US trade deficit last year was the largest in four years and has sparked protectionist sentiment, including threats by Trump to impose a 45 percent tariff on Chinese goods. The single biggest chunk of that trade deficit, some $347 billion, is with China.

China's customs department put its country's trade surplus with the US at $250.79 billion in 2016, $10 billion less than in 2015.

Still, in the decade leading up to 2016, China's exports to the US doubled, as trade between the two countries became easier.

And if the long-term trend is one of expanded growth, there are signs that some of the volatility in growth of the past couple of years may be subsiding. China's foreign trade grew in the fourth quarter of 2016, alleviating concerns of a slowdown.

The Beijing-based General Administration of Customs said the value of trade in the three months to December rose 3.8 percent. Exports were up 0.3 percent and imports rose 8.7 percent. For the entire year, trade dropped 0.9 percent, but that drop was a lot smaller than the 9 percent fall recorded in 2015.

Speaking last month, GAC spokesman Huang Songping said supportive policies, a stabilizing economy in China and rebounding external demand helped support the country's trade.

"China will make efforts to fight uncertainties in the world economy and promote globalization while taking a firm stance against trade protectionism," said Huang.

In many ways, Asian countries aim to deal with the slack created by the retrenchment in the US and Europe by boosting regional trade.

China is a big part of this. Even as its economy slows, the country continues to gobble up raw materials. Oil imports rose 13.6 percent through 2016 to 381 million tons and iron ore imports rose 7.5 percent to a little more than 1 billion tons.

Particularly encouraging was the growth of trade to countries involved in the Belt and Road Initiative — the China-led plan aimed at reviving trade and infrastructure along the ancient Silk Road routes.

Exports to Pakistan, for example, rose 11 percent and to India 6.5 percent. By comparison, exports to China's biggest trade partner, the European Union, increased by just 1.2 percent and exports to the country's third-largest trading partner, ASEAN, fell 2 percent.

In a note, Chinese investment bank China International Capital Corp said it expected better external demand in 2017.

In value terms, however, the figures are a little different. China's trade surplus fell to $40.82 billion. When counted in US dollars, China's exports fell 7.7 percent in December and imports dropped 5.5 percent year-on-year.