'Operation duck' and the student savior

Updated: 2015-07-02 07:50

By He Na(China Daily)

|

||||||||

In mid-1945, a team of US soldiers liberated a Japanese internment camp in East China, freeing more than 2,000 foreign civilians. A young Chinese scholar was also a member of the rescue party, and 70 years later, he's still feted by those he helped to save. He Na reports.

Editor's Note: This is the sixth in a series of special reports about the experiences and influence of foreigners who either lived or served in China between 1937 and 1945.

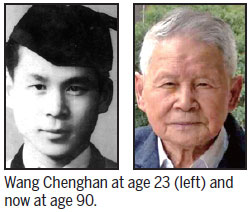

Wang Chenghan, also known as Eddie Wang, is not man who stands out in a crowd. Short of stature, gray-haired and with wrinkles on his face, the 90-year-old is virtually indistinguishable from the elderly people who can be seen dancing in squares across China as they take their daily exercise.

Appearances can be deceptive, though. In conversation, the retired engineer is an impressive person; he has excellent command of English and is deeply knowledgeable about engineering, but his charisma derives in part from an extraordinary experience he had 70 years ago.

In 1945, at the tender age of 20, Wang was the Chinese interpreter for a group of US soldiers who risked their lives by parachuting from a B-24 bomber to liberate Weihsien civilian internment camp in what is now the city of Weifang in Shandong province.

Change of status

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 immediately changed the status of Westerners in China's coastal regions, and in a matter of days they were transformed from untouchable neutrals into enemy aliens.

"The Japanese invaders established many camps worldwide and also in China to intern Allied Westerners, and Weihsien was the largest," wrote Mary Previte, an 82-year-old US national who was interned at age 9, in a recent e-mail exchange with China Daily.

In addition to Previte, who later served in the New Jersey General Assembly, about 2,000 people from 30 countries were interned by the Japanese Imperial Army for more than three years.

The detainees included past and future politicians, artists and scientists, such as R. Jaegher, a foreign-born adviser to Chiang Kai-shek, the Reverend W.M. Hayes, president of the former Huabei Theological Seminary, Olympic gold medalist Eric Liddell and Arthur W. Hummel Jr., who later became US ambassador to China.

According to Xia Baoshu, 83, a Weihsien camp researcher and former president of the Weifang People's Hospital, the camp was once the American Presbyterian Compound, but when the Japanese arrived, they placed electrified barbed wire on top of the walls, dug a moat outside the walls, and erected gun towers that were manned around the clock.

Former internees remembered the place with horror.

"Can you imagine it? I remember being trucked into Weihsien like an animal. My memories of the camp are awash with every kind of misery - plagues of rats, flies, bed bugs," Previte said.

The late Norman Cliff, a Chinese-born British missionary and writer, was 18 when he entered the camp. In his memoir, he wrote that every ounce of energy was spent acquiring fuel, food and clothing.

Angela Louise Cox, a Canadian internee, remembers the terrible conditions in the camp: "Sanitary conditions were very poor. The winters were cruel and there was a lack of medical care. But the overwhelming memory for the detainees was the lack of food." According to Cox, the internees were given three poor-quality meals a day, including thin millet porridge for breakfast every morning, but "it was ever enough".

Canadian Edmund Pearson, 79, a retired engineer and businessman who was 6 when he was interned, said that after being ravenously hungry for more than three years, he would eat almost anything.

"It took a long time before I could deal with the Japanese, even though as an adult I went to live in Hong Kong with my family and had to do business with the Japanese. The people are fine, but the government has never acknowledged what they did to us," he wrote in a 2014 e-mail to China Daily. "My personal encounters with Japanese businessmen happened when I was sent to live in Hong Kong in 1973 to 1975. They all denied being in the war, except for one person," he added.

Lack of experience

Once the decision had been made to liberate the Japanese camps in China, the US military quickly organized nine missions, all of them named after birds. The mission to liberate the Weishen camp, codenamed "Operation Duck", was led by Major Stanley Staiger.

"Eddie Wang accompanied the team as the Chinese interpreter. The team bound for Weihsien flew from Kunming, Yunnan province, in a B-24 plane," Previte said.

Wang started learning English at high school in Chengdu, Sichuan province, and was a sophomore at Sichuan University when he joined the military in December 1944, although he had already undergone training in small arms, light machine guns, and the use of the high explosive, TNT.

Wang was recruited into a telecommunications group in Chongqing where he learned Morse code, and was then sent to interpreter training classes, and completed a 25-day course before being assigned to Operation Duck. His job in Weihsien was to translate anything to do with China for the benefit of the US soldiers.

Seven decades have passed, but Wang still has clear memories of almost everything that happened during the mission. The only thing he cannot recall fully is the parachute jump. He had only received basic training on fixed simulation equipment, and had never actually jumped from an airplane until that day in 1945.

"I always worried making about a real jump. Fortunately, the parachutes used on the mission deployed automatically, which saved my life. When I jumped from the plane, the sudden strong flow of air made me dizzy, almost unconscious," he recalled. Despite his lack of experience, Wang landed safely.

An ecstatic welcome

By early 1945, the Japanese were losing ground in most of China and their defeat was almost assured. The news was withheld from the internees, though, and it wasn't until the arrival of the B-24 on Aug 17, 1945, that they knew their long days in hell were over.

"We wept, hugged, danced, and waved at the plane circling overhead. People poured to the gate to welcome the heroes. All the internees were celebrating liberation, and they even cut off pieces of parachutes, and got rescuers' signatures and buttons to cherish," Previte said.

Wang remembers the warmth of the welcome he and the other members of the group received. "We landed almost a mile away from the camp in the fields of Gaoliang, and were welcomed by the internees. We took over and stayed in what had been the small Japanese headquarters building, not far from the entrance of the camp," he said.

He said two teenage girls taught him to dance after the camp was liberated. "A Greek girl also gave me a piece of parachute silk embroidered with the rescue scene and autographed by all seven liberators, including myself," he said.

Despite the welcoming scenes and the smooth takeover of the camp, the soldiers were fully aware that their mission was a dangerous one.

"Japan had surrendered, but it wasn't known whether all the troops had received the order to surrender, especially those in remote places. For the rescuers it was a life threatening task," said Wang Hao, director of the Weifang Foreign and Overseas Chinese Affairs Office.

Previte recalled that Ensign James W. Moore, one of the US party, told her of the men's concerns at the time. "Would the Japanese in these outposts know that Japan had surrendered? Would it be peace, or would it be guns bristling like needles, pointing at the sky?" she said, paraphrasing the young soldier's words.

Moore also told Previte that the officer commanding the team, Major Staiger, decided that the plane would approach at low altitude, reasoning that they would lose fewer men and less equipment if the Japanese had less time and space to shoot at them and their parachutes.

Endgame

Although Wang finds it difficult to recall the parachute jump, many former internees, including Previte, witnessed the scene. None of them ever forgot the excitement they felt when they saw the emblem of the US Air Force emblazoned on the giant plane.

"It was a Friday. In a scorching heat wave, I was withering with diarrhea, confined to a mattress atop three side-by-side steamer trunks in the second-floor hospital dormitory. Inside the barrier walls of the concentration camp, I heard the drone of an airplane far above the camp," Previte recalled.

Sweating and barefoot, she raced to the dormitory window and watched a plane slowly sweep lower and lower, and then circle again.

"It was instant cure for my diarrhea. I raced for the entry gates and was swept off my feet by the pandemonium. Prisoners ran in circles and pounded the air with their fists," she recalled.

"I watched in disbelief. A giant plane emblazoned with the American star was circling the camp. Americans were waving from the bomber. Leaflets drifted down from the sky," she said.

Weihsien went mad.

After the war, Wang graduated from Sichuan University and became an engineer. He retired in 1990, and has only revisited the camp once, during a business trip to a nearby city. Almost every memento of the raid has either been lost or misplaced over the years, and the only things he has left are a battered duffel bag and his memories. "Objects aren't important," he said. "It's enough to know I helped to make a difference."

Contact the writer at hena@chinadaily.com.cn

Ju Chuanjiang contributed to this story.

|

Estelle Cliff Horne and another former internee are unable to hold back tears when recalling the years they spent at the Weihsien camp in Shandong province. The pair are pictured during a visit in 2005. Ju Chuanjiang / China Daily |

(China Daily 07/02/2015 page6)

- Mass casualties in Indonesian military plane crash

- Japan's LDP lawmaker denounces Abe's security policies

- More than 100 feared dead in Indonesian military plane crash

- More than 50 may die in Indonesian plane crash

- Japan's Diet gets 1.65m signatures against security bills

- Thailand's first MERS case declared free of deadly virus

Western Europe swelters in long-lasting heat wave

Western Europe swelters in long-lasting heat wave

Top 10 shareholders of AIIB

Top 10 shareholders of AIIB

Massive Hello Kitty theme park opens to visitors

Massive Hello Kitty theme park opens to visitors

New terminal of Pyongyang Intl Airport put into use

New terminal of Pyongyang Intl Airport put into use

Ten paintings to remember Xu Beihong

Ten paintings to remember Xu Beihong

Obama hails new chapter in US-Brazil relations

Obama hails new chapter in US-Brazil relations

Boxers top Forbes highest paid celebrities list

Boxers top Forbes highest paid celebrities list

Not so glamorous: Glastonbury ends with sea of rubbish

Not so glamorous: Glastonbury ends with sea of rubbish

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Economic growth driving force for China's future mobility: Think tank

'Operation duck' and the student savior from internment camp

White House lifts ban on cameras during public tours

China, Canada seek to increase agricultural trade

A Canadian comes to Xi'an, finds personal, business success

Fewer Chinese seek US grad schools

US, Cuba to announce reopening of embassies on Wednesday

China bests MDGS for improved drinking water, sanitation

US Weekly

|

|