'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

One for the ages

Updated: 2012-01-08 15:15

By Chitralekha Basu (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

|

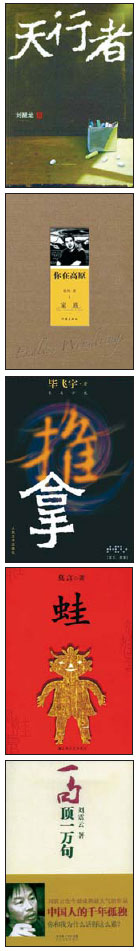

Prize-winning authors (from left) Liu Xinglong, Zhang Wei, Bi Feiyu, Mo Yan and Liu Zhenyun, and their prize-winning works are highlighted in the first edition of Pathlight. Photos provided to China Daily |

The first edition of Pathlight: New Chinese Writing shows the best of Chinese literature to the rest of the world, in the estimation of Chitralekha Basu.

This is a collector's item. And not just because of its obvious historical importance. The first edition of Pathlight: New Chinese Writing magazine is a metaphor of the cooperation between Chinese and Western agencies - in this case, the influential People's Literature magazine, edited by Li Jingze and the Paper Republic team, helmed by Eric Abrahamsen - to showcase Chinese literature to the rest of the world. What an absolute gem this slender 160-page volume is, in terms of the range of voices it covers, some of them translated for the first time. Kudos to the translators for bringing out the varied textures, emotions, cadences and even the visual appeal in some of the lines penned by the featured Chinese writers represent.

For example, translating Qi Ge's never-ending inventories of silverware, spices and muscle names, which tend to overwhelm the reader like pelting rain (The Sugar Blower, translated by Joel Martinsen) would take a different set of sensibilities and acumen than that required to tackle the naive, fable-like charm of Jiang Yitan's story (China Story, translated by Eric Abrahamsen). The labor of love is self-evident.

Pathlight opens with notes by the five 2011 Mao Dun awardees and, in some cases, excerpts from their winning work. Awarded every five years, this is ostensibly China's most influential recognition for writers and comes with a hefty cash reward of 500,000 yuan ($79, 440).

The themes of these writers - all born in the mid-1950s, with the exception of Bi Feiyu, born in 1964 - are loosely about the people of their generation. They are essentially an attempt to capture a slice of the big picture (sometimes a rather big slice, as in Zhang Wei's 10-volume You are on the Highland) since the founding of New China in 1949.

The difference is in the telling. For example, Liu Xinglong's prize-winning book, The Sky Walkers, built around the lives of locally funded rural school teachers from the 1960s to the 1990s, exudes an old-world languorous allure. Days, years, are spent watching clouds morphing in the sky even as rumors of a Kuomintang attack on the mainland float in the air.

By contrast, the excerpt from Liu Zhenyun's A Word is Worth Ten Thousand Words is about grassroots China's encounters with evangelists. An Italian missionary doggedly goes about trying to convert a Chinese butcher, who thinks Lord Jesus might be a man living in the next village who could be persuaded to share a smoke with him. The story is fraught with the pathos of two utterly different people from disparate worlds trying to make sense of each other.

Bi Feiyu's award acceptance speech is the most poetic: "When the shadows cast by blind men overlapped with mine, I understood that this was the modernity I had been thirsting for: respect for limitations, respect for self-control," he says, referring to his novel Massage, a story about blind masseurs.

And Mo Yan's is the most humbling, considering he is easily the most widely known among the awardees and often tipped to win the Nobel.

"Having won the Mao Dun prize, I would try to forget about it 10 minutes later. I must keep in mind that I am not great and that truly great fiction has not yet been invented. I will keep my gaze fixed in that direction, staring toward those brambly, trackless wilds."

But the loveliest thing about this mini anthology is the spotlight focused on the relatively unknown voices.

Di An, who was born in the 1980s, belies the concern that young Chinese writers are too full of themselves, despite the writer's professed anxieties about not being able to make marked progress since the publication of her first book at the age of 19.

Her story, Williams' Tomb, addresses two important issues, particularly poignant in the present Chinese context. The first is homosexuality and shifting gender identities - the protagonist-narrator is born a boy, but is always denigrated by his father for not being man enough, which makes him want to get in touch with his feminine side and fall in love with a man.

Second is the phenomenon of the "wolf father" that is, nowadays, occasionally packaged as a Chinese virtue. In Di An's story, extreme parenting is treated as filial duty. Hounded by his father for all his childhood years and as a young adult, the protagonist escapes to Japan, only to return to donate cells from his liver so that his father might live a little longer. From that point on, both father and son will carry a bit of each other, until the very end.

Rich in cinematic detail, this is the work of a writer who has experienced pain and the meanings embedded in it.

The poetry section features six names, most of them born on the cusp of 1970. These, including the widely translated Xi Chuan, are seasoned, well-honed voices, who have been at their craft for a while, having evolved their own poetic idiom.

I loved the minimalist poems of Yu Xiang, especially the one about making friends with fellow women and then losing them along the way. It's a very universal theme and quite unsentimentally put across.

The grand finale is a story by Li Er, which is irreverent and unsparing about China's emergence in the new world order. It's gripping, as Li Er usually is.

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Health new priority for quake zone

Xi meets US top military officer

Japan's boats driven out of Diaoyu

China mulls online shopping legislation

Bird flu death toll rises to 22

Putin appoints new ambassador to China

Japanese ships blocked from Diaoyu Islands

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

US Weekly

|

|