'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

Eye off the prize

Updated: 2012-01-10 13:56

By Chitralekha Basu and Song Wenwei (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

|

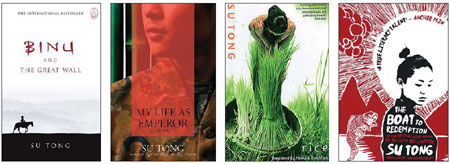

Su Tong is known for his fascination with history and many of his works like (from left) Binu and the Great Wall, My Life as Emperor, Rice and The Boat to Redemption are set in the past. [Photos Provided to China Daily] |

The prize-winning author Su Tong says he is not actively seeking more recognition but is keen to write his magnum opus. Chitralekha Basu and Song Wenwei report.

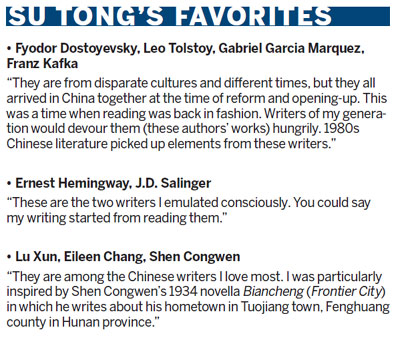

Su Tong first experienced success as a writer in his 20s. In 1993, his name was associated with director Zhang Yimou, when the latter's Raise the Red Lantern, based on Su's short story Wives and Concubines, was nominated for an Academy Award.

Critical recognition, too, has never been in short supply for Su, who effortlessly straddles the twin worlds of China's feudal past and post-independence confusion, its mythological tales of grandeur and operatic romance as well as the bestial ruthlessness and cruelty that marked some of its 20th-century history.

Winning the Man Asian Literary Prize in 2009 for his novel The Boat to Redemption expanded the ambit of his influence, winning him more fans outside of China. The story of a disgraced Communist Party official, who lives on a barge, resigned to the life of a social outcast, set against the backdrop of the "cultural revolution" (1966-76) and seen through the eyes of his teenage son, was also a finalist for the Man Booker International in 2011 - but lost to the American heavyweight Philip Roth.

"Prizes are a matter of luck," Su says, sitting under the chiaroscuro lighting of a Chinese diner in Nanjing, capital of Jiangsu province.

"True, the Man Asian win improved my popularity among English-speakers to an extent, but, at the end of the day, prizes, being the vice-chairman of Jiangsu Writers' Association - these things do not matter. I was reasonably well known in China by the time I was 26. Now I only want to concentrate on my writing."

Anybody who has sampled The Boat to Redemption would agree that the marvelous descriptions of the lives of boatmen in Suzhou Creek, replete with the technical details of a sailor's occupation and an acquired insight into the ways of nature - which sometimes upset the most precise human methods to resist these - would take a total immersion into the subject, on the part of the writer.

Su has combined this with an intuitive understanding of the "cultural revolution" years, as well as a very powerful imagination, using ever-familiar events from Chinese history as a backdrop against which the sordid lives of disgraced Secretary Ku and his relationship with his highly mischievous, and equally dreamy and vulnerable, young son Dongliang are played out. Dongliang's first-person narration often takes a turn for the bizarre and the fantastic, underscoring the point that in 1970s' China, reality is often far more incredible than fiction.

Su has long nursed an urge to publish his take on the "cultural revolution". Born in 1963, Su experienced those tumultuous years from a child's point of view.

"Children have very clear memories of what they see, although they may not fully understand what's happening," Su says.

He remembers the tremendous upheavals that people around him were subjected to, how those in authority "suddenly fell from grace" and "spouses began publicly denouncing each other it was a total destruction of morality. People were suspicious of everything and everybody. There was general distrust all around".

The layered and extremely fraught father-son bonding in the story was partially inspired by Su's own relationship with his civil servant father. "In China, traditionally, fathers have controlled their children's lives. I remember my father stopping me from wearing a light blue vest that was my favorite," Su says.

He also wanted to share his understanding of the ways of the river.

Born in Suzhou, Jiangsu province, Su grew up in watery terrain. Whenever there was too much traffic on the river, vessels would dock close to his house, giving him a chance to go onboard and observe.

How Dongliang wrestles with the river until he learns to decode its mysteries, embracing a life on the waters and renouncing society, is also a major theme in the book.

"Ironically," Su says, "Dongliang's friend Huaxin, the feral girl, who is a force of nature, goes back to the land, while Dongliang decides to stay on, on the waves."

Indeed, in times of great historical upheavals, there is no knowing who will be who in the end.

Known for his fascination with the past - Binu and the Great Wall is set in mythological times, My Life as Emperor focuses on imperial China and Rice looks at the 1930s pre-revolution years of famine - Su's next book, due in 2012, is about contemporary times.

"It's about two boys and a girl, born in the 1980s, growing up in a small-town neighborhood in China, until they are in their 30s, in the present decade, that is," Su says.

"Actually, it's more about how much Chinese society has changed in these years, as seen through their eyes," he adds, on second thought.

His style has evolved markedly. The unsparing depiction of soulless cruelty and sexual violence in his earlier novel Rice has given way to a slightly more sympathetic and generous view of the world.

"Rice was an experimental project," Su says. "Like a mathematician, I was trying to figure out what the greatest value put on human evil might work out to be."

He admits the exercise affected him physically as it caused him mental anguish. "In fact, a female neighbor told me, 'You look like a decent enough guy. How could you bring yourself to write this?'" Su says.

He has sworn off that kind of writing, he says.

In fact, Su rarely revisits his earlier works. He might want to rewrite them all over again, if he did, he says. "So I'm always looking forward to the future, to my next novel."

He does have ambitions about writing a magnum opus.

"That's the reason for a writer to want to continue living, is it not?" he asks, rhetorically. But he doesn't believe that it would have to be about grand themes.

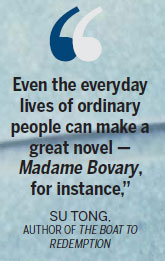

"Even the everyday lives of ordinary people can make a great novel - Madame Bovary, for instance," he says.

Like the French novelist Gustave Flaubert, Su is also a believer in the beauty that lies in details, in finding le mot juste - the right word. It's the telling of a story that's of primary importance. Grand themes could come second.

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Health new priority for quake zone

Xi meets US top military officer

Japan's boats driven out of Diaoyu

China mulls online shopping legislation

Bird flu death toll rises to 22

Putin appoints new ambassador to China

Japanese ships blocked from Diaoyu Islands

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

US Weekly

|

|