'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

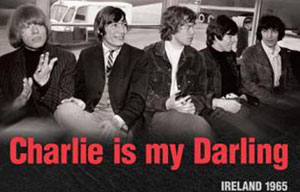

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

Paper vs pixels

Updated: 2012-03-22 10:05

By Mei Jia (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

|

Clockwise from top left: Writer Murong Xuecun, managing director of Penguin China Jo Lusby, head of Qidian copyright management center Luo Li and veteran publisher of Phoenix Publishing &Media Liu Feng. Photos Provided to China Daily |

In the world's largest consumer market, millions of books are sold every day - in all forms, even as traditional publishers face off the competition from e-books and the online business module. Mei Jia files the war reports.

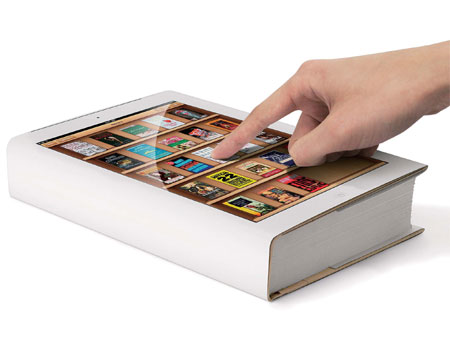

Doomsayers predict that books in print are dying out. And if you keep your eyes peeled on China's subway trains and buses, you may be convinced that today's readers are more likely to be browsing novels on their tablets, pads, phones or mini laptops than carrying an actual book. Even the venerable 244-year-old Encyclopedia Britannica announced this week that it will no longer print those red-and-black hardcover sets that were once a status symbol in every middle-class home from Southampton to Shanghai. And there is the undeniable fact that half the private bookshops in China have gone bankrupt in the last 10 years. But, there are signs that it is going to be a long-drawn battle.

Printed books are determined to stay alive, propped up by their own unique advantages and also because the world of e-books is still very much frontier territory.

There may even be a new symbiotic relationship developing between paper and pixel.

Writer Murong Xuecun rose to fame riding the first crest of China's earliest online wave at the beginning of the millennium.

His sensational novel Leave Me Alone: A Novel of Chengdu was written in serialized installments that had millions of fans following eagerly on the web.

The novel was the hottest thing on online forums.

When it was later published in print form, it still sold a million copies, Murong says. His novel is now available in English as well.

But after adopting the same formula for several later works, Murong decided to revert to a traditional publisher in 2010 when he released his latest work, based on his undercover expose of illegal pyramid marketing schemes.

"The reason is simple," says Murong.

"I have to earn money to sustain myself, and printed books, at least, bring in the royalties."

He got no money from his online success earlier, and the author says that the several contracts on digital rights he signed in recent years brought in only 50,000 yuan ($7,890), hardly enough for bread and butter.

Murong enjoys his influence in the cyber world, but he admits that "being published is also a measure of pride".

"Anyone can write online," he says, "but a book that gets printed undergoes a selection process with professional scrutiny and quality control."

Murong feels that books on paper are irreplaceable, even though the publishing industry may atrophy as digital editions grow in strength. He is not alone in feeling that print will still be around, although there are signs that its survival may, oddly enough, depend on what appears online, too.

Many of the most popular cyber books have sister publications in print.

To cater to readers with a preference for paper rather than pixels, the country's largest online literature site Qidian runs a copyright management center.

Luo Li heads that center and is one of the founders of the website. He believes paper publications empower online works because both editions are complementary and form a reciprocal partnership.

Luo's comments are backed by the success of the publishing empire that is Qidian's mother corporation. It boasts the copyrights of 5.8 million digital works and has 194 million online users. By the end of 2011, it had 1.6 million registered writers posting an average of 60 million words a day.

In 2011, Qidian commanded 43.8 percent of China's online literature market in terms of revenues.

It is recognized as the pioneer business model for combining a writers' agency with a platform in which readers pay for reading the books online.

The Sky of Doupo, a voluminous fantasy novel, and Every Step Surprises Your Heart, a time-traveling love epic, are just two recent hits. The former has attracted many clicks online, and in print, it has sold more than 2 million copies.

"We started as a service for our writers in 2006 when we had our first online writer earning one million yuan ($158,000)," he says. "As these writers turn professional, we expanded our business into partnering with publishers to support them."

Luo believes the number of readers undecided between traditional and e-books is small, but having books in both editions help publishers draw in consumers from both markets, including those in the gray area of indecision.

"Our printed book buyers are partly loyal fans who have read the books online, and partly new readers attracted by the online hits," he says. For them, the e-books also serve as good market indicators on reader tastes and preferences.

Though Luo believes e-reading may be the mainstream platform in the future, the extinction of printed books may not come soon, he feels.

He has some advice, too, for those bemoaning the threat from cyber works.

"Traditional publishers should stop being so self-pitying," he says. "E-publishing is relatively new in China and its advocates are fewer in comparison to the old guards."

The Chinese publishing industry generated 1.27 trillion yuan in revenue in 2010, of which e-publishing contributed 105 billion yuan as its fastest growing sector, according to Liu Binjie, head of General Administration of Press and Publication.

Liu notes that the number of mobile-phone subscribers who regularly log online reached 318 million in 2010, and 43.3 percent are readers who generated 35 billion yuan revenue for e-publishers.

These are attractive figures and irresistible to those eager to exploit the marketing potential digital publishing may offer.

"We are all aware that the consumer e-book market has not yet taken off in China," says Jo Lusby, managing director of Penguin China, mainly because there is still a lack of credible "consumer platforms and business models", she adds.

Lusby says Penguin China's business continues to grow and that growth comes entirely from printed books at present. Penguin sees a robust future for both formats.

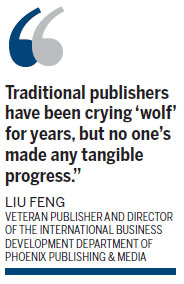

"Traditional publishers have been crying 'wolf' for years, but no one's made any tangible progress," says Liu Feng, veteran publisher and director of the international business development department of Phoenix Publishing &Media, the Jiangsu-based group which is one of the country's largest.

"But I am amazed by our US counterparts. They were also aware of the market trends and suddenly in 2010, many of them changed strategies and tactics, and started putting things online," Liu says, hardly able to mask the anxiety in his voice. In contrast, Chinese publishers are still lagging behind when it comes to switching tacks.

They have had to do a lot of adapting in recent years. Most of the larger publishers started off as State-administered institutions, which converted into full-fledged companies responsible for their own bottom lines. Just as they have gotten comfortable with internal changes, they now have to face the challenge from e-books.

"Although most of these publishing houses are starting to establish or develop e-business," Liu says, "they may find themselves heading towards a dead-end if they have no determined direction."

"Slogans are not part of productive power," he adds.

Li Pengyi, the president of the China Education Publishing &Media Group, believes there is still time for that learning curve, because "content is still paramount" in publishing, as he told a gathering of top publishers at a forum in 2011.

Li's rationale is that these older, larger publishing big brothers have the advantage of having professional editors, a reservoir of writers and the proper editing support and experience.

Phoenix's Liu also holds that printed books will stay alive because there must be options and choices for readers. "The force of habit is strong," he said.

Besides, Liu, Murong, Luo and Lusby all agree on one thing. Books in print will always be collectors' items, whether they are read, or not. The only thing they cannot agree on is when the printed word will become obsolete.

Some say it will be in 20 years. Other say it will be many more decades before it finally happens. But then, 20 years ago, no one thought you could read books on a phone either.

Contact the writer at meijia@chinadaily.com.cn.

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Health new priority for quake zone

Xi meets US top military officer

Japan's boats driven out of Diaoyu

China mulls online shopping legislation

Bird flu death toll rises to 22

Putin appoints new ambassador to China

Japanese ships blocked from Diaoyu Islands

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

US Weekly

|

|