'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

Writing for their suppers

Updated: 2012-04-11 09:30

By Yang Guang (China Daily)

|

||||||||

Mao Dun Literature Prize winner Liu Xinglong says the money he was paid for a novella he wrote wasn't even enough to treat his friends for a meal.

His words have made literary circles and publishing industry insiders worry that poor remuneration could cost contemporary Chinese literature sustainable originality.

In response, Liu Binjie, director of the General Administration of Press and Publication and the National Copyright Administration, revealed in a recent interview with China National Radio that the remuneration standard for published written works would be raised.

"The current standard that was laid down almost 20 years ago is quite low," he says.

According to Regulations of Remuneration for Published Written Works, promulgated by the National Copyright Administration in 1999, the basic remuneration standard for "original works" is set at 30-100 yuan ($4.80-15.90) per 1,000 words.

Zhang Hongbo, secretary-general of China Written Works Copyright Society, says the society has been commissioned to carry out research in preparation for setting up a reasonable new remuneration standard.

Mao Dun Literature Prize winner Bi Feiyu recalls he was paid 1,700 yuan ($270) for his debut novella, The Lonely Island, in 1991, which was equivalent then to what he would draw as three years' salary.

"The amount I am paid has increased, but it only equals one month's salary," he says.

Shanghai-based literary magazines Harvest and Shanghai Literature doubled their minimum contribution remuneration standard to 160 yuan per 1,000 words in 2010, with some outstanding pieces receiving 400 yuan per 1,000 words. Its effect was strong and immediate, thanks to a special fund provided by the Shanghai municipal government.

Besides the basic remuneration, writers have other sources of income as well - royalties, for instance.

According to Cao Yuanyong, deputy chief editor of Shanghai Literature and Art Publishing House, the royalty percentage for first-class writers ranges from 10 to 15.

"It is not low at all," he says. "The crux is, sales are not good enough - books that sell about 100,000 copies can be counted as bestsellers."

"Piracy is a big problem," says Zhao Changtian, chief editor of Shanghai-based Mengya magazine.

Chinese Writers' Rich List, an annual list initiated by Wu Huaiyao in 2006, shows that the country's top-earning writer in 2011 was 29-year-old Guo Jingming, with a total income of 24.5 million yuan ($3.9 million).

"Such a figure might not be able to squeeze in the top 10 rich list of other industries," Guo says.

According to Forbes magazine, the world's highest-paid writer, American thriller writer James Patterson, raked in $84 million last year.

"Many writers in China have persevered despite their low incomes. I hope readers will pay them more attention and support them by buying legal, instead of pirated, copies of their works."

Online writers have also emerged in recent years. According to a Xinhua News Agency report, the number of online writers in China amounted to more than 1 million by 2011, while the number of online readers has reached 194 million.

Readers pay 2-3 yuan for reading 100,000 words online, which are shared by the websites and writers.

Online writer Nanpai Sanshu, runner-up on last year's writers' rich list, says among online writers, an annual income of more than 1 million yuan is nothing to boast of.

"Some are able to earn 10 million yuan a year," he says. "If it were not for the pirated books, they could afford helicopters."

But he also admits that such a group is only "the top of the pyramid", compared with the multitudes of online writers.

The adaptation of literature into films and TV series is also a source of income for writers. Bi Feiyu, for instance, says much of his income comes from film and TV adaptations of his works.

Popular film Love Is Not Blind and hit TV series Naked Wedding are both adapted from online literature, whose rights were sold for hundreds of thousands of yuan.

In addition, there are also examples of fantasy literature being adapted into online games.

"Although the literature market has witnessed considerable growth in the previous couple of years, the reading of literature in China still doesn't amount to much," says Sun Qingguo, manager of Beijing OpenBook, a group specializing in monitoring books' retail sales.

According to Sun, literature takes up about 10 percent of the entire Chinese book market, while it is 40 percent in the United States and 35-40 percent in Europe.

"In the end, it is the reading demands that prompt good writers and sustain their living standards," he says.

yangguang@chinadaily.com.cn

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

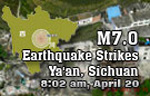

Health new priority for quake zone

Xi meets US top military officer

Japan's boats driven out of Diaoyu

China mulls online shopping legislation

Bird flu death toll rises to 22

Putin appoints new ambassador to China

Japanese ships blocked from Diaoyu Islands

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

US Weekly

|

|