'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

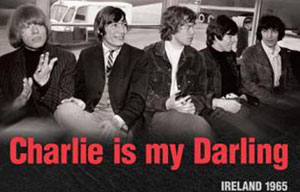

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

Visions of a lost civilization

Updated: 2012-04-13 14:43

By Bruce Humes (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

|

The Ewenki songstress Alima plays the lead role of a shaman in the film adapted from the novel Right Bank of the Ergun. Provided to China Daily |

Chi Zijian's characters exist in a world that is both banal and mundane, but it is one that is also filled with the rituals and magic of the semi-nomadic, animistic culture of the Greater Hinggan Mountains. Bruce Humes reports

The 46-year-old author Chi Zijian, from Heilongjiang province, has already won several awards, including the Lu Xun Literature Prize, and the 2008 Mao Dun Literature Prize, for her best-selling novel, Right Bank of the Ergun (E'erguna He You'an).

The latter is soon to be a film starring the popular and photogenic Ewenki songstress Alima and directed by Yang Minghua, a member of the Daur ethnic group.

Many of Chi's female contemporaries focus on urban life, but Chi chooses to avoid the hustle and bustle of the cities. Instead, she writes about the simple, even banal, life of rural people in the northernmost region of China.

Ironically, Chi's devotion to such "localized" tales may win her global recognition. London-based publisher Harvill Secker recently snapped up the English-language rights to Right Bank of the Ergun.

This means that it will join Wolf Totem (Jiang Rong) and Harmonious Land (Fan Wen) to form a select trio. All are contemporary works of fiction about ethnic groups in China and all have been purchased by top-flight publishers in the West.

Chi's choice of a female, non-Han, first-person narrator for her novel, however, is a bold experiment.

A young Han man "sent down" to the countryside of Inner Mongolia autonomous region during the "cultural revolution" (1966-76), narrates Wolf Totem, and we remain observers of the Mongolian herders. Harmonious Land - which features, sometimes, violent collisions between French Catholic missionaries, Han officials, Naxi Dongba shamanists and Tibetans on the Yunnan-Tibet border - is narrated in the third person.

The narrator of Right Bank of the Ergun remains nameless. We learn that she is an Ewenki destined to marry and outlive the last chieftain of her ulileng (clan members who live and hunt together).

Now an elder, she elects to remain behind when her tribe abandons the forested mountains of Northeast China for "civilized" life in town, where their beloved reindeer will be cooped up like cattle.

Intrigued by the immense amount of detail that gives the novel such authenticity, I asked Chi how she acquired her knowledge of the Ewenki.

"The branch of the Ewenki I wrote about resided in the Greater Hinggan Mountains, and I lived in that area from my childhood," she says. "So I was very familiar with the environment. But I consulted a huge amount of written records about the Ewenki and their customs, and took notes that were very helpful."

She also visited the Aoluguya Ewenki who had relocated outside Genhe city in Inner Mongolia autonomous region, staying with them several days, drinking their reindeer milk tea, and listening to their songs.

"I didn't conduct one-on-one interviews per se. That's because a novel isn't a news report that requires detailed data. A novel is all about creating a 'sense of space'. The tribe's last shaman had already died, so I learned many stories about her from the mouths of others."

Is that where she found the model for her narrator, I wondered.

"No, I didn't interview the woman who served as my protagonist. I just borrowed her 'shell' to tell a tale that covers almost a century."

Chi movingly sketches the tragic decline of this semi-nomadic, animistic people up through the closing years of the 20th century.

Her portrayal of Nihao, a "reluctant" female shaman, is utterly spellbinding.

A series of bizarre events intimate that Nihao will be the "new" shaman with the ending of the three-year mourning period for the former shaman Nidu.

Nihao announces that a new sacred reindeer - a "Malu King" that transports the wooden statue of the clan's Malu spirit - is soon to appear. And sure enough, a rare white reindeer is born.

It gradually becomes clear that Nihao is an extraordinarily powerful shaman, but tragically, for each sick person for whom she performs a successful trance dance, she must pay a frightening price.

When a father from a neighboring village without a shaman comes to beg Nihao to perform a ritual for his dying son, Nihao feels a shiver run down her back.

"You don't have to go and save him!" cries Maria, an elderly woman in the tribe.

"I am a shaman," says Nihao bleakly. "How can I watch death approach and not save him?"

And she starts singing a dirge for Guogeli, her own son, whose life will surely be taken in exchange.

And what drove Chi to write the book?

"I wanted to establish the basis for a certain credence, there is a logic to the Ewenki way of life. Those things that everyone defines as 'barbaric' may well be a kind of civilization that has been lost to us."

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Health new priority for quake zone

Xi meets US top military officer

Japan's boats driven out of Diaoyu

China mulls online shopping legislation

Bird flu death toll rises to 22

Putin appoints new ambassador to China

Japanese ships blocked from Diaoyu Islands

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

US Weekly

|

|