'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

Other worldly

Updated: 2012-04-18 09:57

By Chitralekha Basu and Sun Li (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

|

Anni Baobei has a big fan base as an online writer. Provided to China Daily |

Related: What they say

Described as a writer ahead of her time, Anni Baobei reveals rare bits of her personal life and explains the spiritual themes in her prose to Chitralekha Basu and Sun Li.

Earlier this year we were at a posh Chinese diner, with the writer Li Er and a few literary friends. We got talking about Anni Baobei and her magazine Da-Fang (O-Pen). The manageress caught the name and came over to our table, asking if we could get Anni to join us. "I would give you a 50 percent discount, if she did," she said. That is Anni's clout.

Nearly 14 years after she started posting stories of love and longing in Chinese cities, Anni Baobei's fan base continues to grow. From being a youth icon of urban angst, Anni now resonates with a mature audience, who, like her translator Keiko Wong, find comfort in revisiting her works, a decade after they were written.

Anni (Li Jie is her real name, but she is best known by her pen name Anni Baobei) was an instant online sensation in 1998 - at a time when only a few million Chinese had online access and did not usually go on the Web to read a novel. But Anni, who got there early, clicked with a nascent audience, who would soon multiply into several millions - each eager to check out the Anni phenomenon.

"Anni brought freshness to online writing, as opposed to the flamboyant style then in vogue," says her publisher Lu Jinbo. "She often omitted the subject in the sentence and used unconventional punctuation."

She was in her mid-20s then - a little listless and fragile, an artistic individual who had quit a secure job with a national bank against her parents' wishes as she tried to find her feet in Shanghai.

The recurring theme in Anni's stories of a sensitive and lovelorn young woman is, expectedly, seen as projections of the writer's own personality. Her main character is usually a writer, who listens to Paganini, wears sneakers without socks, drops by at Starbucks and gets entangled in agonizingly complicated relationships. Often named Qiao, the vulnerable-romantic protagonists of Anni's fiction were a generic model that a generation of young women, and men - caught up in the unsparing whirl of China's big cities - could identify with. Goodbye Vivian, published in print in 2000, unleashed a wave of pirated editions.

But that was then. Today, however, Anni would like to be identified with themes that run deeper than the anxieties of disorientated urban youth - the sort that resulted in an immediate connect with her audience and turned her into a bestseller brand.

She takes her career as a writer far more seriously than when she started posting her fiction, somewhat casually, on the web. Anni is trying to explore lofty philosophical ideas in the Buddhist sutras, read up Chinese and Japanese classical texts, traveled extensively in Japan, India and Europe - all these with a view of becoming a more equipped, accomplished and consistently prolific writer.

At the moment, Anni is readying a collection of essays for release in the last quarter of the year. "It's about my musings on certain themes, like reading, traveling, watching films - all written in the form of a diary. I'd like to believe I've managed to add more depth to my earlier understanding of things in this one," she says.

"Increasingly, I am trying to delve more into human nature," Anni tells us, when we meet her in a cafe in Beijing's cosmopolitan Wangjing area, where she now lives. The characters in her novels have aged with the writer, "although it's still about their struggles with the environment and other things" that make her themes.

And they are getting more spiritual. In one of her earlier novels, Lotus (2006), two strangers who have given up on society, meet by happenstance and take a journey across the inhospitable Tibetan plateau to get in touch with their inner selves.

"Once I tried to write a book set in ancient times about the Indian notion of karma," Anni tells us. "But I need more time to delve into a subject as complicated as this."

She traveled in 2011 to Bodhgaya in India last year, to the site where the Buddha meditated to attain enlightenment and brought back several poignant shots of monks at prayer that were featured in Da-Fang. Sadly, it is no longer in circulation.

"Buddhist ideas will continue to influence my work though perhaps not directly figure in it," says Anni. "It is a philosophy I want to explore. I do not believe in it as a religion."

"Her early writings were about people seeking the meaning of life; longing for love, whether that of parents and children, or romantic love," says Keiko Wong, who translated some of Anni's stories in The Road of Others - the first collection of Anni's fiction in English translation, published by Make Do Studios in March. "Previously it was about people trying to figure out where they stood in society, seeking a way out, fighting with desperation. But now Anni's writing is more focused on seeking the meaning of and maintaining love, appreciating the personality differences between people and loneliness as well as appreciating life. While most of her early stories usually led to a dead end, the recent ones are more about solutions."

This cultivated approach, Anni agrees, had something to do with motherhood. "I am beginning to look at life and the world through the eyes of my 4-year-old daughter," says Anni, somewhat unexpectedly, given her legendary tightlipped-ness about her personal life. "Earlier, I was a lot more pessimistic. It's my daughter who helped me see the world in a mature way."

"I would like to be a role model for my daughter. I would like to be stronger, more mature and more hardworking for my daughter's sake," she adds, for the first time, betraying a soft, emotional side to what is often assumed to be her Sphinx-like composure.

All these years, Anni has been jealously guarding her private little world from public glare, rarely making an appearance and steadfastly refusing media interviews. As a matter of rule, Anni never responds to readers' comments on her blog.

"I wish Anni was more active on her blog and micro blog," says Ning Ying, 29, a fan who has been reading every word Anni wrote since she was in high school. "Given she never appears in public, this is the only way we could know her thoughts."

Anni's answer to that would be - I am what I write.

As Wong reminds us, "Talking of her book Spring Banquet in 2011, Anni said in an online interview that all she could possibly say about the book, could be found in the book itself."

"I am an intensely private person," Anni tells us. "I do not feel natural or comfortable talking to strangers."

But could this reclusiveness also be read as a conscious packaging of a hugely-attractive public personality who refuses to appear in public?

"I am aloof to the outside world," says Anni. "I do not care too much about my public image or the so-called mystique."

Anni, reminds Lu Jinbo, is always a step ahead of the rest.

"When the Chinese were just about getting familiar with writing on the Web, Anni was already an established online writer. When Starbucks and Ikea caught on with the Chinese urban young, Anni was through with writing about them and had turned her focus to the simplicity of human nature, minus the trappings, like in Lotus," says Lu.

Anni is trying to glean the best from the East and the West. She has something to take from the philosophy of Nietzsche as well as the Taoist book of Zhuangzi.

"I feel a deep bond with Song Dynasty sensibilities and cultural elements. I play the guqin, burn incense, and prefer a slow-paced ancient style of life."

At the same time, contemporary themes, such as big cities in the throes of a tremendous transformation, attract her.

In her last novel, Spring Banquet, she explores the phenomenon of traditional Chinese cultural elements disappearing under the onslaught of foreign culture. "That's one of my themes," she says, concernedly.

Contact the writers through sunli@chinadaily.com.cn.

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

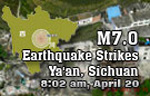

Health new priority for quake zone

Xi meets US top military officer

Japan's boats driven out of Diaoyu

China mulls online shopping legislation

Bird flu death toll rises to 22

Putin appoints new ambassador to China

Japanese ships blocked from Diaoyu Islands

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

US Weekly

|

|