'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

Rural revelation

Updated: 2012-05-02 18:07

By Liu Jun (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

|

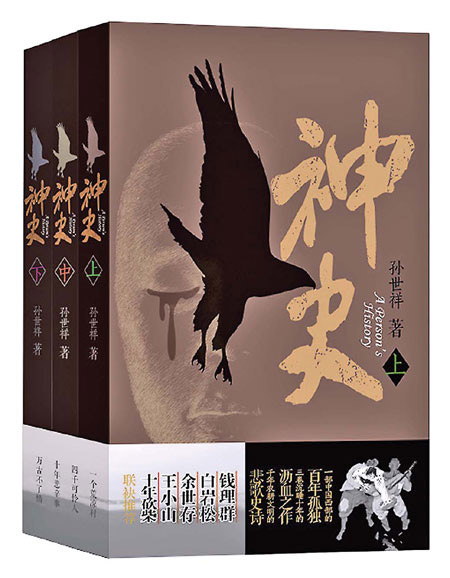

Sun Shixiang's book The Story of a God became well-acclaimed after his premature death. Photos Provided to China Daily |

Sun Shixiang, who wrote Story of a God, dies as a little-known author. But his candid fiction on China's countryside is set to raise his profile. Liu Jun reports.

Passengers on the subway during Beijing's rush hour might have wondered why I was on the brink of tears. I was simply engrossed in Story of a God (Shen Shi, yet untranslated), a down-to-earth narration by little-known author Sun Shixiang, who died in 2001 at just 32. It's daunting take - three bulky volumes involving hundreds of characters plus crude editing, the book is a worthy choice for anyone wishing to gain a deeper insight into present-day China. Published in 2004 and reprinted by Language & Culture Press in 2011, the book reveals the harsh realities of the countryside as the farmers' son Sun Fugui fights tooth and nail for a better life outside his hometown in mountain-locked Yunnan province.

The author based the novel primarily on his own struggles. He died of liver cirrhosis, while carrying out surveys in the countryside for a provincial government organization.

His experiences as a teacher in a township middle school and as a journalist in the provincial capital Kunming provide firsthand and authentic details about farmers eking out a living in one of the country's poorest areas.

The book begins with the arrival of a new teacher in Fala village in the Wumeng Mountains of northeastern Yunnan, where layers of perilous peaks block the settlement from modern life and most villagers don't care about the outside world.

As his hosts bake potatoes for the honored guest, the teacher tries not to cover his nose as pigs rumble in ankle-deep mud in the dark room.

The teacher later learns from village elders that generations of logging, mining and wars have wiped out the area's pristine forests.

Villagers fight for roots of grass or bamboo to make fire or spend the whole day just to get a bucket of water from many miles away.

Accompanying this utter poverty are illiteracy, ignorance and corruption. Even the pettiest official who controls a few bags of chemical fertilizers could garner villagers' awe and huge profits.

No wonder most people would rather send precious hams and grains to cultivate relations with powerful families than send their children to school.

While few girls in the village attend school, most young men loaf away their lives playing truant, gambling, chasing girls, joining armed gangs and then becoming weighed down by life's burdens once married.

Against such a backdrop, the teacher is overjoyed to find a talented student, Sun Fugui.

Unlike most students, the young man devours all the books he can find and develops critical thinking.

He owes his achievements entirely to his parents' steadfast support. When all the family's pigs, horses and chickens die, his parents borrow money and toil three times as hard so he can continue his studies.

A central message of the book is that education is the only way for someone to shake off the shackles that bind him from birth and to help fellow farmers lead more fulfilling lives.

Like protagonists in all successful novels, Sun is a multifaceted character, who reflects the merits and shortcomings of mankind.

Sun Fugui (meaning "rich and powerful") renames himself Tianchou ("friend of heaven") and then Tianzhu ("master of heaven") as he grows up.

He dreams of regenerating the Chinese nation and going down in history like Qin Shihuang (259 BC-210 BC), the emperor who first united China, or Chairman Mao.

But the young man is confined by his conditions and, thus, makes many bad decisions. For example, he chooses not to study English, because he believes that if China is strong enough, the rest of the world should study Chinese.

He also chooses to rely on himself and not on relations. For many of his peers, the shortcut to success is to marry a girl from a powerful family. Sun has many such chances, thanks to his literary talent, but he doesn't seize them.

The family tries various ways to rise out of the marshland of poverty, such as searching for mineral deposits and selling medicinal herbs, but all their ventures end in failure.

Sun later moves to Guangdong province's capital Guangzhou to seek a better life. But he gets robbed and goes hungry for days until an ex-girlfriend rescues him.

Against the glamorous windows of posh restaurants, the lonely young man sees the contrast of the wrinkled, forlorn faces of his kinsmen.

Such deep feelings for the people lay a solid foundation for the novel.

When the author died, he left behind piles of poems, novels, reviews of ancient classics, and analyses of the countryside and China's future.

His brothers and friends sorted out some of his works, and Story of a God has won good reviews from readers and critics.

Nonetheless, the novel is still amateurish. Some parts need vigorous editing to make it a better read.

But his candid account of rural life overshadows his weaknesses. There have been loads of works of fiction about rural China, but Story of a God excels with the author's inseparable bonds with and deep insights into the barren fields that bred him.

In a way, the book reminds one of Jean-Christophe by French writer Romain Rolland, because both heroes persist with their noble ideals and are defiant to worldly gains and sufferings.

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

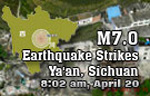

Health new priority for quake zone

Xi meets US top military officer

Japan's boats driven out of Diaoyu

China mulls online shopping legislation

Bird flu death toll rises to 22

Putin appoints new ambassador to China

Japanese ships blocked from Diaoyu Islands

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

US Weekly

|

|