'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

Buddhist teaches Zen of Google

Updated: 2012-05-21 13:31

By Caitlin Kelly (The New York Times)

|

||||||||

|

|

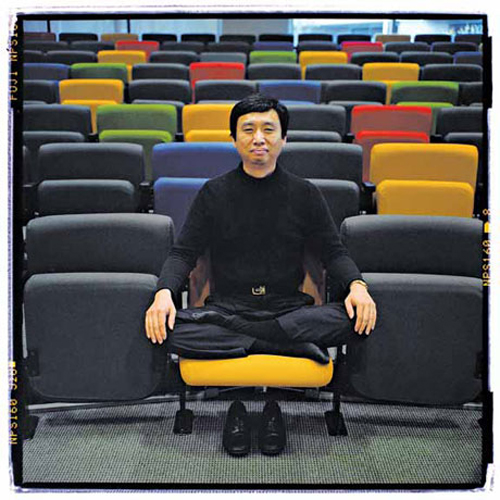

Google hired Chade-Meng Tan as an engineer, but he now teaches a popular course in mindfulness at work. [Photo/Agencies] |

An engineer's class offers coping skills

Mluntain view, California

Step onto Google's campus here - with its indoor treehouse, volleyball court and heated toilet seats - and you might think you've just sailed over the rainbow. But all the toys and perks belie the frenetic pace here, and many employees acknowledge that life at Google can be hard on fragile egos.

Employees coming from fast-paced fields, already accustomed to demanding bosses and long hours, say Google pushes them to produce at a pace even faster than they could have imagined.

Google's co-founder and chief executive, Larry Page, recently promised on the company Web site to maintain "a healthy disregard for the impossible."

Little wonder, then, that among the hundreds of free classes that Google offers to employees, one of the most popular is called S.I.Y., for "Search Inside Yourself." It is the brainchild of Chade-Meng Tan, 41, an engineer who arrived at Google in 2000 as employee No. 107 and now works in human resources.

Think of S.I.Y. as the Zen of Google. Mr. Tan dreamed up the course and refined it with the help of nine experts in the use of mindfulness at work. And in a time when Google has come under scrutiny from European and United States regulators over privacy and other issues, a class in mindfulness might be a good thing. The class has three steps: attention training, self-knowledge and self-mastery, and the creation of useful mental habits. More than 1,000 Google employees have taken the class, and there's a waiting list of 30 when it's offered, four times a year. The class accepts 60 people and runs seven weeks.

Richard Fernandez, director of executive development and a psychologist by training, says he sees a significant difference in his work behavior since taking the class. "I'm definitely much more resilient as a leader," he says. "I listen more carefully and with less reactivity in high-stakes meetings. I work with a lot of senior executives who can be very demanding, but that doesn't faze me anymore. It's almost an emotional and mental bank account. I've now got much more of a buffer there."

Mr. Tan says the course has received good reviews. "In anonymous surveys, on average, participants rated it around 4.75 out of 5," he says. "Awareness is spread almost entirely by word-of-mouth by alumni, and that alone already created more demand than we can currently serve."

Mr. Tan's first book, "Search Inside Yourself: The Unexpected Path to Achieving Success, Happiness (and World Peace)" is to be published in 17 markets worldwide, from South Korea to Brazil to Slovenia.

A Buddhist for many years, Mr. Tan, born and raised in Singapore, taught himself how to write software code at the age of 12. And by 15, he had won his first national academic award. At 17, he was one of four members of the national software championship team.

"In Singapore, the way to distinguish yourself is to win competitions," he says. "I wasn't any happier. There was a compulsion to be the best."

Mr. Tan says that he wants to create world peace. "I don't want to sound megalomaniac, but my whole life is about doing something for the world, from as far back as I can remember."

Mr. Tan studied computer engineering in Singapore and attended graduate school at the University of California, Santa Barbara. He was offered a job by Google, he says, within five minutes of e-mailing his resume after graduation.

Recently, about 50 people filed into an amphitheater at Google. Mr. Tan was at the podium with a fellow teacher, Marc Lesser, a former Zen monk who is the author of two books. For two hours, employees worked with partners to perform exercises in identifying and sharing emotions. The class offers students a place to question why and how they behave. Here, wielding superior technical skills or intelligence won't suffice.

Like Mr. Tan, many S.I.Y. students are highly educated immigrants from Asia. This course challenges them to examine how their choices affect their work and relationships. "We need an expert," Mr. Tan says as the class begins. "That expert is you. This class is to help you discover what you already know."

One exercise asks everyone to name, and share with a partner, three core values. "It centers you," one man says afterward. "You can go through life forgetting what they are."

In one seven-minute exercise, participants are asked to write, nonstop, how they envision their lives in five years. Mr. Tan ends it by tapping a Tibetan brass singing bowl. They discuss what it means to succeed, and to fail.

"Success and failure are emotional and physiological experiences," Mr. Tan says. "We need to deal with them in a way that is present and calm."

Then Mr. Lesser asks the entire room to shout in unison: "I failed!"

"We need to see failure in a kind, gentle and generous way," he says. "Let's see if we can explore these emotions without grasping."

Blaise Pabon, an enterprise sales engineer, took the class in 2009. "The notion of S.I.Y. is more radical or countercultural here at Google than anywhere else," he says. "The pressure here is really quite intense. It's a place filled with high achievers trained to find validation through external factors."

One tool the course teaches is S.B.N.R.R. - Stop, Breathe, Notice, Reflect and Respond. "Business is a machine made out of people," says Bill Duane, a Google engineer. "If you have people, you have problems. You can have friction between them or smoothness."

Can S.I.Y. translate to other companies and corporate cultures?

As Mr. Pabon says: "The reason I think it will be broadly applicable is that everyone struggles. 'Am I the smartest person in the room? What if I'm not?' They're worried about losing their job. Everyone's got some fear of not being able to survive."

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Health new priority for quake zone

Xi meets US top military officer

Japan's boats driven out of Diaoyu

China mulls online shopping legislation

Bird flu death toll rises to 22

Putin appoints new ambassador to China

Japanese ships blocked from Diaoyu Islands

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

US Weekly

|

|