'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

A blind woman's talent for words

Updated: 2012-05-22 10:15

By Wang Kaihao (China Daily)

|

||||||||

Related: Reading without seeing

Shi Ran's computer doesn't have a screen - she doesn't need it.

Neither does the 30-year-old proofreader need her stylish sunglasses - hip specs that make it difficult for most people to realize she's blind.

She moves her fingers along a keyboard-like Braille reading device, while her colleague reads paragraphs aloud at the Beijing-based China Braille Press (CBP).

The team translates Chinese characters into pinyin, and then pinyin into Braille. Proofreaders make sure no mistakes creep through.

"It's much more complicated than English Braille," Shi says.

"Chinese isn't written using an alphabet, and pauses in ancient prose are always confusing. And a regular book becomes several times thicker when being translated into Braille, so our proofreading speed is much slower than other presses'."

The 15 pairs of proofreaders can each crunch about 20,000 characters a day.

"Not everyone can do this job," CBP senior editor Huang Qiusheng says.

"Proofreaders must be meticulous and have professional backgrounds."

A quarter of CBP's books are about traditional tuina (hands-on body treatment) massage therapy, which is a common job for China's blind.

Shi became the first blind college student from Jiangsu province when she studied TCM at the Special Education College of Changchun University in 2000. She worked as a TCM clinic assistant in her hometown, Jiangsu's Zhenjiang, for two years before coming to the publishing house.

"I have experience in medicine and love books, especially ancient prose and poems, so this is a job made for me," Shi says.

She's satisfied with her job, although her salary hardly covers her expenses.

Shi says an obstacle for blind people to develop medical careers is that they're not allowed to receive physician licenses.

She was born with congenital glaucoma and gradually lost her sight. She went totally blind within three days at age 13.

"Sound means more to me than it does to others," she says.

"One of my favorite pastimes is listening to talking mynas in parks."

She began to learn piano at age 5. But playing music was difficult, she says. "I could hardly see the score even when the characters were several times larger than usual. I had to put my face right in front of it."

Shi's mother, 53-year-old Li Qiuyun, says her daughter studied hard and competed with classmates, which might have damaged her vision. Teachers permitted her to skip some homework, but Shi never did.

Shi remains calm when talking about the time she went blind but doesn't say much about it, aside from "it changed my life path". But it was once the "end of the world" to her parents.

"We couldn't cope when we were told our daughter was blind," Li recalls, in a trembling voice. "We were too shocked to cry, but I still felt tears streaming down my face."

Shi stayed at home for a year before transferring to a school for the blind in Jiangsu's provincial capital Nanjing. She simultaneously passed the nation's highest exam for amateur pianists.

Her parents took her from Nanjing to Shanghai to learn piano every weekend for the following five years. Her father had to quit his bank job and start his own business to cover the tuition fees.

"I won't give up music," Shi says. "It's not necessary to be a professional."

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

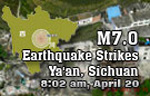

Health new priority for quake zone

Xi meets US top military officer

Japan's boats driven out of Diaoyu

China mulls online shopping legislation

Bird flu death toll rises to 22

Putin appoints new ambassador to China

Japanese ships blocked from Diaoyu Islands

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

US Weekly

|

|