'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

A classy little primer on the country's education

Updated: 2012-05-22 14:07

By Obio Ntia (China Daily)

|

||||||||

Lisa Carducci has no intention of leaving China. The educator, philanthropist and writer who has lived in the country since 1991 is among the first to receive permanent resident status in China.

During her recent visit to Ningbo, Zhejiang province, she was excited to discuss her latest book, Work in Progress: Chinese Education From a Foreign Expert's Perspective, published by China Intercontinental Press.

The work is a thoroughly researched survey of the educational status, problems and opportunities related to ongoing educational reform.

Carducci manages to weave together a work that is a leisurely read, a notable feat considering how many news references, research institute studies, government statistics and expert quotes she intersperses within the pages.

She's a columnist for China Daily and draws heavily on the paper for information.

Carducci directly addresses cheating, plagiarism and the issue of false credentials at all levels of China's educational system. And she calls for a change in the general attitude toward writing papers in China.

Some readers may be shocked to discover how extensive the underground market for buying academic papers is.

Her coverage of the dissertation ghostwriting industry is set out in a clear and comprehensive way.

She refers to one ghostwriting company in Wuhan, capital of Hubei province, which hired 80 people to produce academic papers that ended up in more than 200 published journals.

There's the 26-year-old bilingual ghostwriter in Beijing who charges between 130 and 200 yuan ($20 and $32; the higher rate for English) per page and can complete bachelor's level work in two days or spend more than a week on higher-level work.

There's the US-educated online ghostwriting businesswoman who will write a 20,000-character master's degree paper for around 4,500 yuan.

Carducci's review of academic dishonesty gives weight to her call for change in China's education system, especially by fostering creativity in the classroom.

Her descriptions of past teaching methods aimed at fostering creativity and critical thinking that she employed in Canada and China will resonate with educators who are pass ionate about inspiring students.

Education in China is such a broad topic to cover in one work that a reader is justified to doubt the depth that a 200-page book on the topic can deliver. Those who are interested in almost any aspect of the modern Chinese educational system, however, will have many of their pet interests addressed.

Her book has sections covering such topics as English-language profiteering and the proliferation of tutoring and test preparation firms in China, the lack of quality, the income gap, rural education, the study abroad wave, the return of overseas-educated Chinese (also known as "sea turtles") and migrant workers' children. It also has close examinations of conditions in Xinjiang autonomous region and Qinghai province's Tibetan areas.

While Carducci covers these topics with the sensitivity of an earnest career teacher and a two-decade China expat, the downside of her broad approach is that the book ultimately has a relative lack of focus.

This would be a significant flaw if Work in Progress were an academic treatise. But Carducci, as she writes in her foreword, set out to write a "non-academic document - pages I would like you to turn with pleasure instead of effort".

As an introductory reader for casual consumption, this book delivers upon the author's stated goal because it compiles a wealth of valuable information and enlightens readers on so many facets of education in the country.

The writer is the senior college counseling director of Zhejiang province for Dipont Education Management Group.

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

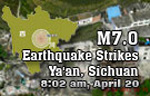

Health new priority for quake zone

Xi meets US top military officer

Japan's boats driven out of Diaoyu

China mulls online shopping legislation

Bird flu death toll rises to 22

Putin appoints new ambassador to China

Japanese ships blocked from Diaoyu Islands

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

US Weekly

|

|