'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

Olympians are forever

Updated: 2012-08-12 09:08

By Wang Kaihao (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

|

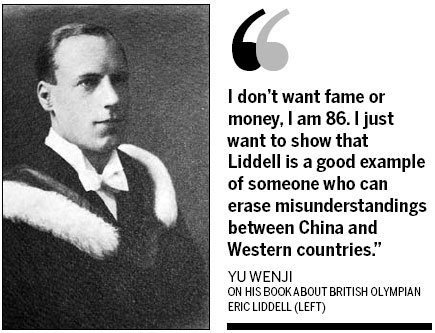

Yu Wenji says his memory of Eric Liddell hasn't faded even as he ages. Wang Kaihao / China Daily |

The story of Eric Liddell is celebrated in the film Chariots of Fire and in a new book on the athlete by a resident of Tianjin who knew him well. Wang Kaihao reports in Tianjin.

Yu Wenji, 86, is half-blind. But when he heard the theme music from the 1981 British movie Chariots of Fire, in which Eric Liddell is one of the two athlete protagonists, during the Opening Ceremony of the London Olympic Games on TV, the Tianjin resident says he almost burst into tears.

|

Related readings: |

"I watched the movie three times in row when I first got the videotape," he says. "He (Liddell) always leans back his head when crossing the finishing line. That scene is still vivid in my mind."

Yu spent 15 years writing a biography of Liddell, which was published in 2009. He has finished a revised version of the book, which he hopes will be published this year as a celebration of Liddell's 110th birthday.

Liddell, gold medallist in the men's 400m at the 1924 Paris Olympic Games, was born to a Scottish missionary family in Tianjin in 1902, and left China at the age of 5. He returned to his birthplace in 1925, when he began to teach at the Tientsin (old spelling of Tianjin) Anglo-Chinese College (TACC) serving the London Missionary Society. His Chinese name is Li Airui.

TACC was built in 1902 as a college. It was one of the first schools established by foreign missionaries in Tianjin, and was changed into a high school in 1930.

In 1938, the 12-year-old Yu was at elementary school, loved singing and occasionally went to a church nearby to join the choir.

"Liddell played tennis on the weekends. I was the last one to leave the church one day and he stopped me to ask if I wanted to be his ball boy."

Yu took the job, and helped Liddell for one year. Liddell often chatted with him when taking a rest by the tennis court.

"He told me people were born on the same starting line, but the results were different, so people needed talent and high expectations for the future so as not to let down the healthy body given by God."

Yu says this amiable former champion gave him several English textbooks and encouraged him to study hard, inspiring him to pass the difficult TACC entrance exam. Fourteen people from three generations of Yu's family studied there. The big and wealthy family then ran a store selling foreign products.

He says Liddell would practice running around school in the morning and sometimes at Minyuan Stadium in the British concession.

Liddell helped design this stadium and based it on the blueprint of Stamford Bridge, Chelsea Football Club's home ground, shortly after he returned to China. He still sporadically competed after being a teacher at TACC.

Minyuan is where he took part in his last formal competition and won his last gold medal, in 1929. He also trained Chinese athlete Wu Bixian, a high jumper who later participated in the 1936 Berlin Olympic Games.

Liddell busily shuttled between TACC and the countryside in Xiaozhang, Hebei province, as he also held a position there at a church hospital. Yu regrets that Liddell was never his teacher, though he did occasionally substitute for absent teachers.

"I still remember the first English class he taught us. It was about how to tell time in English," Yu switches from his Tianjin dialect to a British accent English recalling the content in that class.

"His English was simple but very humorous," Yu says. "But he was very serious when protecting students' rights. He once quarreled with the headmaster to ask for more subsidies for students not from wealthy families."

However, after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, Yu never saw Liddell again.

The school was occupied by Japanese troops and Liddell was detained in Weihsien (old spelling of Weixian, today's Weifang, Shandong province) Internment Camp, which imprisoned more than 2,000 Westerners living in China, including 300 children.

"He had the chance to leave for Canada with his pregnant wife and two children, but he refused to leave his brothers in church behind. I guess that must have been a tough decision for him," Yu says.

Liddell continued teaching class and organizing games in the camp. Norman Cliff, a British Christian at the camp, later wrote a memoir declaring: "(Liddell is) the finest Christian gentleman it has been my pleasure to meet. In all the time in the camp, I never heard him say a bad word about anybody."

Although Japan offered a prisoner-of-war exchange plan after early 1944, three times, allowing about 200 internees to be released, Liddell would not leave. Though on the British government list he gave up his place to children. He died of a brain tumor six months before Japan surrendered.

"His loyalty greatly inspired me," Yu says.

Yu joined the United States Marine Corps, stationed in Tianjin in 1946, as a part-time bar tender at the military club to cover his living expenses at college, as his family's business failed. When US troops left China, his commanders were satisfied with his job and wanted him to go to the US.

"They even promised US citizenship, but I refused. I told them, `I am Chinese'," Yu says.

However, this experience and his family background caused Yu a lot of trouble during the "cultural revolution" (1966-76). He was an ordinary worker at a post office for decades, even though he speaks excellent English and has finance and engineering degrees.

Yu did not speak about TACC or Liddell for years, until Aug 29, 1993.

On that day, he accidentally met David Mitchell, an Australia-born Canadian from a Hong Kong-based foundation in memory of Eric Liddell. Mitchell was 9 when he was imprisoned at Weihsien Internment Camp.

"He offered me a photocopy of Liddell's death certificate at the camp," Yu says. "It was supposed to have been destroyed by the Japanese when they retreated."

Mitchell told him a Christian Japanese soldier secretly preserved the certificate when he was supposed to destroy it.

The nostalgic Yu was excited to collect more relevant material and completed the book, Li Airui's Brief Biography, in 2008.

Yu has now completed a revised version of the book and expects to get it published by the end of 2012. He also plans an English version of the book.

"I don't want fame or money," he says. "I am 86. I just want to show that Liddell is a good example of someone who can erase misunderstandings between China and Western countries."

He is delighted to see people paying more attention to Liddell during the current Olympic Games, but he also hopes it is not a fad.

TACC buildings were destroyed in the devastating Tangshan earthquake of 1976. After several renovations, Minyuan Stadium is also being demolished. The only other building related to Liddell that is still standing is the hospital where he was born.

Jin Pengyu, a cityscape and architecture expert in Tianjin, who is helping promote Yu's book, says the municipal government plans to build a sports museum in 2013, which will introduce Liddell's story. Yu says he is happy to provide materials.

Yu also formerly had a brain tumor like Liddell. His life was saved after an operation in 1999. He later got baptized, decades after attending missionary school, to mark his rebirth.

"Maybe my eyesight and brain are not that keen after the operation, but my memory of Liddell is always fresh."

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Health new priority for quake zone

Xi meets US top military officer

Japan's boats driven out of Diaoyu

China mulls online shopping legislation

Bird flu death toll rises to 22

Putin appoints new ambassador to China

Japanese ships blocked from Diaoyu Islands

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

US Weekly

|

|

Photos:

Photos: Photos:

Photos: Photos:

Photos: