'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

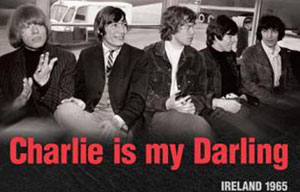

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

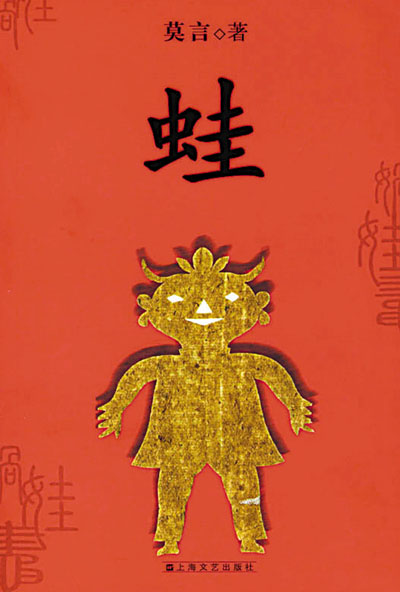

Ambivalent amphibian

Updated: 2012-10-11 19:47

By Liu Jun (China Daily)

|

||||||||

Reading Mo Yan's latest novel, Wa (Frogs, 2009), is both rewarding and unsettling. Like all his previous works, this one is full of action and drama. But while his earlier works created heroic protagonists like "My Grandpa" and "My Grandma" who waged war against Japanese invaders in the past, Frogs chronicles the painful, almost bizarre, modernization of the "Northeast Gaomi Township", which Mo has created over the past decades based on his rural hometown in East China's Shandong province.

Tension and a surprising dark humor come from a cast of characters named after human organs, such as Chen Bi (nose) and his wife Wang Dan (gall bladder), Xiao Shangchun (upper lip) and his son Xiachun (lower lip).

The chief character, "My Aunt" Wan Xin (heart), was seen as a fairy godmother in her youth because she was a modern midwife who delivered roughly 10,000 babies. But as national family planning kicked in, she quickly degenerated into the demon incarnation as it fell upon her shoulders to enforce the policy, a hard choice for the world's most populous nation.

The description of the three deaths she causes in the pursuit of errantly pregnant women is so striking that her flight from an army of revengeful frogs pales by comparison.

In ancient mythology, frog is a totem of fertility and its name "wa" is a phonetic synonym to baby or child.

"My Aunt" later tries to atone for her crimes by breathing life into pottery babies, which are sold as popular souvenirs to tourists eager for offsprings.

But the thin line of morality is again blurred as the once upright midwife helps her nephew Ke Dou (Tadpole, the narrator of the story) and his infertile wife have a baby through a surrogate mother.

The plot flashes by at lightning speed, leaving the reader very much depressed at the end.

The latter part of the novel clearly drew inspiration from social events, such as a toy factory fire that killed and deformed hundreds of migrant women workers, and the underground surrogate mothers serving the rich and powerful.

It is a time when black and white are no longer distinct and against a background set in shades of grey, the bizarre becomes normal as materialistic cravings erode the human conscience. The only consolation offered is a reminder to love life.

Each of the book's chapters carries a letter from Ke Dou to a Japanese writer. Though Mo denies this is Oe Kenzaburo, who won the Nobel Prize for literature in 1994 and had visited Mo's hometown, meeting his aunt, prototype of "My Aunt", he did admit drawing much inspiration from that trip.

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

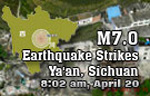

Health new priority for quake zone

Xi meets US top military officer

Japan's boats driven out of Diaoyu

China mulls online shopping legislation

Bird flu death toll rises to 22

Putin appoints new ambassador to China

Japanese ships blocked from Diaoyu Islands

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

US Weekly

|

|