'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

Words for the world

Updated: 2012-10-15 09:15

By Cecily Liu and Zhang Chunyan (China Daily)

|

||||||||

In recent years, she says, Chinese writers as varied as Wei Hui, Yu Hua, Yan Lianke - and, of course, Mo Yan himself - have produced work that resonates more with international audiences than works from earlier periods.

Meanwhile, the notion of so-called "world literature" - the idea that works of literature can move beyond their origins and circulate globally - has gained academic currency. This will likely lead to more Chinese literature appearing in bookstores, libraries and university curricula, she says.

London's independent literary agent Toby Eady, who represents many Chinese writers, including Yu Dan, met Mo about 15 years ago in China.

Related: From books to blockbusters

Eady praised Mo as a great writer, adding that his contribution to literature is the equivalent of Dickens'.

But Eady says: "I still think Mo Yan's writing - and, to an extent, all Chinese writing - are not truly understood by Western readers because a part of Chinese literature is lost in translation."

Howard Goldblatt has done a good job in translating Mo's work, but the variety of Chinese vocabulary doesn't translate well into English, Eady says.

Translation is perhaps the most important dimension of Chinese literature's global acceptance.

University of Leeds' Chinese studies lecturer Frances Weightman says: "One reason why the reception of Chinese literature in the West has been problematic is the lack of people with the requisite language skills to read it in the original."

Hillenbrand explains: "The business of translating Chinese literature is booming as never before, and established figures are being joined by a talented cohort of younger translators. But this momentum needs to be maintained if Chinese literature breaks through permanently onto the global market."

She believes it's no coincidence that China's latest Nobel laureate is one of the most prolifically translated contemporary Chinese writers, Hillenbrand notes.

Hockx says: "We need more translators, especially foreign translators, who know good Chinese and can translate the work into their own languages in a way that foreign readers will appreciate and understand."

Good translators have been crucial to Mo's international success.

France is where his works were most widely translated and published outside of China.

The French interest in Mo's works was initially sparked by Zhang Yimou's film based on Mo's novel Red Sorghum. To date, 18 of Mo's books have been translated into French and published by two major publishing houses - Editions du Seuil and Editions Philippe Picquier.

Anne Sastourne, editor of the French translations of Mo's works at Editions du Seuil, says Mo is obviously intelligent but always calm and only speaks as needed.

"His openness, his human feelings and intellectual concentration can really be felt in his books," says Sastourne, who has met Mo several times. "We guess French readers are not very well acquainted with the Chinese world and may find it somewhat confusing. But still, they are very curious about and love (his) exotic, powerful and colorful style."

Editions Philippe Picquier's founder Philippe Picquier says it was Mo's "original voice, wild imagination (and) the poetic style of the storytelling" that won French readers.

His company has been publishing Chinese literature for 26 years and started to publish Mo's works in 1993.

Mo's novels Big Breasts and Wide Hips and Life and Death Are Wearing Me Out are among his most popular works in France.

Sastourne says Mo's Nobel will give Chinese literature more visibility in France.

"It will be a new step and should bring more readers to Mo Yan's works first and to others as well," she says.

Li Xiang in Paris and Fu Jing in Brussels contributed to this story.

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

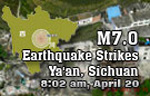

Health new priority for quake zone

Xi meets US top military officer

Japan's boats driven out of Diaoyu

China mulls online shopping legislation

Bird flu death toll rises to 22

Putin appoints new ambassador to China

Japanese ships blocked from Diaoyu Islands

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

US Weekly

|

|