Displaying the legacy of China's Grand Canal

Updated: 2016-09-04 10:16

By Xu Lin(China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

|

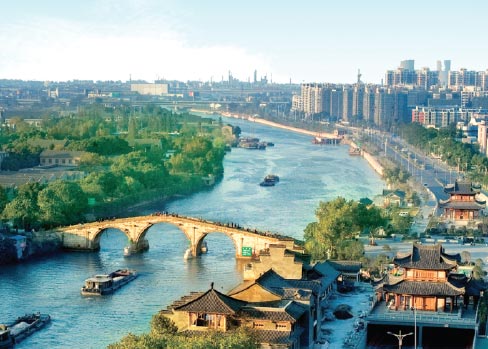

Gongchen Bridge is the landmark of the Grand Canal in Hangzhou. "Gongchen" literally means "respecting the emperor" in Chinese. [Photo provided to China Daily] |

Cargo ships still sail on the 39-kilometer-long Hangzhou section of the waterway, which has become a tourist attraction thanks to its scenic beauty, culture and history.

Hopping on a pleasure boat, modeled on the traditional craft that once transported grain, you start a brilliant one-hour journey at Wulinmen port.

A night cruise promises memorable views. Along the banks, traditional Chinese architecture is colorfully lit up, and the buildings' bright reflections glitter in the water. Fog slowly rises amid the greenery and the combination with lights on the ground makes for a visual wonderland.

"The canal in Hangzhou is unique because it fostered Hangzhou's integration with other Chinese cities. It has a long history, with grain-transporting and port culture," says Zhu Qunying, a manager at the Hangzhou Grand Canal Group Culture and Tourism Company.

The company has just improved the lighting on the canal at night. And next year, it will expand access to buses and ferries and offer public bike-rental services and stores, making it easy to transfer between land and water, and tour around the canal.

Illuminated onshore as you pass is a beautiful woman in traditional Chinese costume playing the guqin, or the Chinese zither, and you can clearly hear the melody from the boat's stereo set.

All the bridges you see have different relief images, with scenes showing the lifestyles of local residents in ancient times.

The boat turns and returns to Wulinmen port once it reaches the Gongchen Bridge. The structure, which is about 400 years old, is believed to be the largest arch stone bridge among the city's ancient bridges.

Along the canal, there are also four museums and the Workmanship Demonstration Pavilion, which were originally old factory buildings and storehouses.

The pavilion showcases more than 20 kinds of craftsmanship, such as traditional embroidery, egg-carving and leather-tooling. Experts offer training sessions for adults and children.

According to an old Chinese saying: "It's futile to draw water with a bamboo basket". But at the pavilion, 60-year-old craftsman Zhang Xinrong makes a bamboo basket that defies it.

"It's solid enough to keep goldfish in," says Zhang, who has been weaving bamboo for 40 years.

"To pass on the craft, it is important to have innovation. I am willing to teach whoever wants to learn to weave bamboo," he says.

In the countryside, weaving daily necessities from bamboo was popular in the old days, but such items have largely been replaced by plastic or stainless-steel goods.

Zhang not only makes replicas of traditional items for exhibition, but also creates modern merchandise such as leather purses with a woven bamboo surface.

He also uses very thin layers of bamboo strips, and dyes them to weave elegant Chinese landscape paintings and calligraphies.

As for the museums, you can visit the China Umbrellas Museum, the China Knives, Scissors and Swords Museum, the China Fans Museum and the Hangzhou Arts and Crafts Museum.

The museums showcase the history, culture and production processes used to make these daily use items and local handicrafts.

Hangzhou is an important producer of traditional oilpaper umbrellas and West Lake silk umbrellas.

They are complicated to make, with bamboo used as the umbrella stem and for the ribs. The canopies flaunt pretty photos, including those of the scenic sites of Hangzhou.

Separately, a group of sculptures show how craftsmen made and repaired umbrellas in ancient times.

In ancient China, a red umbrella was believed to be auspicious, with the power to exorcise evil spirits. So, when scholars traveled to the capital to take an imperial examination, they carried books and a red umbrella for safety and success.

In some ethnic groups in China, an umbrella is seen a token of love.

In one well-known story, a white snake fairy falls in love with a young scholar, Xu Xian, at West Lake. And when they meet, Xu gives her an umbrella because it's raining.

Fans are, however, more personal items and have more meaning.

China has various types of fans-folding fans, leaf fans and silk fans-each with exquisite designs.

In the Tang Dynasty (AD 618-907), a bride would use a round fan to cover her face until the wedding ceremony ended.

Fans were also given as gifts as a symbol of friendship in Chinese history, especially among scholars.

As for scissors, the Zhangxiaoquan scissors originated in Hangzhou more than 300 years ago. They are a staple in every household.

The museum has statues of craftsmen making the scissors as well as videos showing the 36 procedures required to make one, from fine grinding and to creating elegant patterns on the metal.

Speaking about the process, Ding Jican, 53, who has been making scissors for 38 years, says: "One has to endure hardships and work hard to make these scissors. And, nowadays, innovation is about new patterns, such as curves of the handles."

Meanwhile. ferries can also take you to other ports along the canal, such as the Tangxi ancient town, which has old residences, and a seven-arch stone bridge, called the Guangji Bridge.

The town also offers traditional local snacks including pastries, and a chance to pick seasonal fruits such as cherries and loquats.

Fact box

China's Grand Canal, the longest artificial waterway in the world, was inscribed on the World Heritage list on June 22, 2014. The Grand Canal starts from Tongzhou District of Beijing in the north and runs 1,794 kilometers southward to Hangzhou. The project traverses five major rivers in China, the Haihe River, the Yellow River, the Huaihe River, the Yangtze River and the Qiantang River, and six provinces. It was built beginning in AD 605 during the Sui Dynasty (AD 581-618) to enable transport of surplus grain from the agriculturally rich Yangtze and Huaihe River valleys to feed the capital cities and large standing armies in northern China.

- Rousseff appeals impeachment to Supreme Court

- Europeans displeased with their education systems

- Singapore Zika cases top 150; China steps up arrivals checks

- Artists respond to 9/11 attacks in new exhibit

- Rocket explodes on launch pad in blow to Elon Musk's SpaceX

- Record number of Americans dislike Hillary Clinton: poll

Commemorative G20 stamps a hit at media center

Commemorative G20 stamps a hit at media center

Ten photos from around China: Aug 26- Sept 1

Ten photos from around China: Aug 26- Sept 1

Hangzhou: Paradise for connoisseurs of tea

Hangzhou: Paradise for connoisseurs of tea

Top 10 trends in China's internet development

Top 10 trends in China's internet development

Childhood captured in raw, emotive black and white

Childhood captured in raw, emotive black and white

Korean ethnic dance drama shines in Beijing

Korean ethnic dance drama shines in Beijing

Children explore science and technology at museum

Children explore science and technology at museum

Children wearing Hanfu attend writing ceremony

Children wearing Hanfu attend writing ceremony

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Trump outlines anti-terror plan, proposing extreme vetting for immigrants

Phelps puts spotlight on cupping

US launches airstrikes against IS targets in Libya's Sirte

Ministry slams US-Korean THAAD deployment

Two police officers shot at protest in Dallas

Abe's blame game reveals his policies failing to get results

Ending wildlife trafficking must be policy priority in Asia

Effects of supply-side reform take time to be seen

US Weekly

|

|