Cave art's echoing influence explored

Updated: 2013-12-16 11:47

By Caroline Berg in New York (China Daily USA)

|

|||||||||

|

A museum-goer studies one of the offerings at the China Institute's Inspired by Dunhuang: Re-Creation in Contemporary Chinese Art exhibit in Manhattan. Carolin Berg / China Daily |

Whether it is a tree and its roots or an ocean and its rivers, everything has a source, including art.

This notion is what inspired Willow Weilan Hai, director of the China Institute Gallery in New York, to study the art in China's ancient Dunhuang Caves as a source of influence or inspiration for contemporary Chinese artists.

"I think this exhibition raises a fundamental question about a kind of cultural genetics," said Jerome Silbergeld, the P.Y. and Kinmay W. Tang professor of Chinese art history at Princeton University and director of Princeton's Tang Center for East Asian Art. "And this has to do with the notion of influence, and a related notion of inspiration."

Silbergeld and Hai, co-curators of the China Institute's new exhibition - Inspired by Dunhuang: Re-creation in Contemporary Chinese Art - spoke at the institute Friday night.

This is the year of Dunhuang at China Institute. The current exhibition, which will be on display until June 8, 2014, is the second installation based on Dunhuang art to be showcased at the institute this year. The first show - Dunhuang: Buddhist Art at the Gateway of the Silk Road - went on display in the spring and featured the traditional art from the caves.

Dunhuang, located in Gansu province in western China, was a major stop on the ancient Silk Road. The Dunhuang Caves - also known as the Mogao Caves, the Mogao Grottoes or the Caves of the Thousand Buddhas - form a network of 492 temples. The first caves were carved out in 366 AD as places for Buddhist meditation and worship, and more than 800 caves still exist today.

"These caves are filled with murals, sculptures, reliefs and architecture," Hai said of the UNESCO world heritage site. "It's the only site in China that contains so much in only one location and with such a long history."

It was this history that Hai said she felt compelled to find a connection with contemporary artworks in China.

"The exhibition represents 24 works from 15 artists from one root of Dunhuang-inspired artists," Hai said. "[There are] 15 different ways to explore how Dunhuang inspired these artists and how these artists created work from this inspiration."

For instance, Daqian Zhang is considered one of the earliest modern artists to visit Dunhuang, where he stayed for nearly three years in the early 1940s to study its murals. He produced almost 300 copies and held an exhibition in 1943, which helped bring Dunhuang into the limelight. Over his career, Zhang produced forgeries and original works based on the art he found in the caves.

"We're supposed to think that in a world of art, the good artist is that rare genius that goes it alone, who lives in an influence-free bubble and who influences others without being influenced themselves," Silbergeld said in his lecture.

However, virtually every painter was and is a copyist, Silbergeld said.

"Only occasionally this artistic borrowing is simple and direct as stealing software or airplane production secrets or producing Gucci bags and Prada footwear," he said. "Artistic borrowing is a universal affair."

The great expressionist Pablo Picasso once said, "Good artists borrow. Great artists steal." As Silbergeld noted, the artist wasn't the first person to say this, so even this aphorism he either borrowed or stole.

The difference, Sibergeld said, is the borrower merely reproduces art, whereas the thief makes something unrecognizable out of what he took. In other words, if an artist has been influenced, you can see the connection easily. If an artist has been inspired, they do not merely copy an artwork, but a new creativity is triggered.

"The great artist makes what he has taken so different that it can't be returned and therefore it must be considered to have been stolen," he said. "Most important to know is what to take, what to steal, and what will allow the artist to create something new and of his own."

The curator said the artists in the current Dunhuang exhibition scarcely represent one another because they all saw and took away different things to blend their inspirations from this old art with their own contemporary state of mind.

"I think what this exhibition is all about really is tradition and learning," Silbergeld said. "What is remarkable about this [exhibition] is you can find the way [Dunhuang] mattered in each artist's work, and yet it all comes out so different."

carolineberg@chinadailyusa.com

(China Daily USA 12/16/2013 page2)

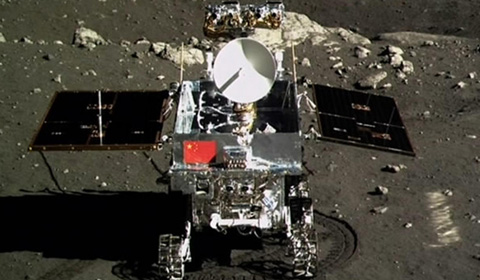

Moon rover, lander photograph each other

Moon rover, lander photograph each other

With a hole in its heart, South Africa buries Mandela

With a hole in its heart, South Africa buries Mandela

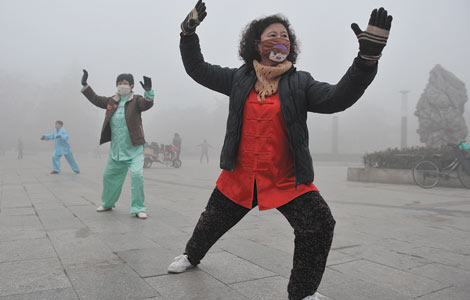

After the storm

After the storm

Guangzhou beats Al-Ahly 2-0 at Club World Cup

Guangzhou beats Al-Ahly 2-0 at Club World Cup

Two students wounded in US school shooting

Two students wounded in US school shooting

21 died in Xinjiang coal mine explosion

21 died in Xinjiang coal mine explosion

Mandela's body transferred to Qunu village

Mandela's body transferred to Qunu village

Postgraduates get hard lessons at job fair

Postgraduates get hard lessons at job fair

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Chinese law firm expands in US

Chinese law firm expands in US

Complacency hinders US energy-saving strategies

China plans its Chang'e-5 lunar probe

Dialogue urged after naval incident

Chang'e-3 mission 'complete success'

Cave art's wide influence explored

DPRK leader's aunt unscathed after purge

Funding, market key to urbanization

US Weekly

|

|