Economist eyes China's transformation

Updated: 2014-08-29 13:03

By Chen Weihua in Washington(China Daily USA)

|

|||||||||

Nicholas Lardy, one of the leading economists on China in the United States, has been very excited about the economic reform plans rolled out at the Third Plenum of the 18th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China last November.

The Third Plenum has promised to give market forces a bigger say in the economy and also laid out an agenda for financial reforms.

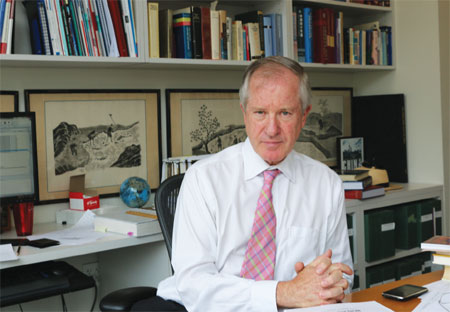

"I think the blueprint is excellent. The question is implementation," said Lardy, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics based in Washington.

Lardy warned that if reforms are not implemented, and credits continue to expand and the level of investment still accelerates over the next three to four years, then the outcome could be very different.

"Then there is a high possibility of a hard landing and much slower growth," he said.

Lardy has seen positive signs. He said China's economy is moving in the right direction, with private consumption in GDP rising in each of the last three years, albeit gradually, current account surplus going down from 10 percent in 2007 to 2 percent now, and a service sector growing more rapidly than GDP for the first time in a long while.

Employment growth has also been strong despite a slow-down of GDP growth. And contrary to what many believe, Lardy argued that slower growth can also generate many jobs, since much of the service sector is quite labor intensive.

Lardy believes rapid growth of wages and employment in China will create more favorable conditions for consumption.

Setting priorities

While praising the Third Plenum blueprint, Lardy pointed out that it was not very good on setting priorities, such as what should be done first.

"I am very big on interest rate liberalization because I think it's key to a lot of the other things. I am very big on reducing the power of monopolized sectors to allow the entry of private businesses," he said.

In his view, if the liberalization of interest rates takes place, the deposit rates and lending rates will go up, and that will bring down the rate of investment.

High interest rates will also lead to more lending to the private sector, according to Lardy, citing the example that the return on investment in the private manufacturing sector is 15 percent compared with only 5 percent for State firms.

While Lardy does not believe the reforms can and should be done overnight since a sudden rise of interest rate, for example, could cause a lot of companies with debt to go bankrupt.

"What you need to do is to get on a path where interest rates are rising," he said. That will send a signal to companies that the cost of capital is going up and they need to get to a level of being efficient and sustainable.

"I think China has been in a low-interest environment for a long time," Lardy said.

Lardy believes it's a mistake for China to protect the monopolies of State companies that are not very efficient, citing figures in his upcoming book Markets Over Mao: The Rise of Private Business in China, to be released this September.

Even on the monopoly side, Lardy said progress has already been made in oil and gas and telecom sectors, but less so on the financial sector. And China's leaders have fully realized the need to bring down the credit growth and growth rate of investment.

"That's what my reading of what the Third Plenum is really shooting for, to get more efficiency, and making the market a more decisive factor in allocating resources," he said.

Successful reforms

As one of the few US economists who have studied the Chinese economy since the 1960s, Lardy described China's reform since 1978 as "wildly successful". The economy is 25 times bigger today than it was in 1978 in real terms.

"I am not talking about PPP (purchasing power parity) or anything like that," he said. "So the growth has been unprecedented."

Lardy expressed his disappointment that reforms in the past decade had slowed down quite a bit and there was a restoration of state in the economy.

However, his upcoming book argues to the contrary of what many believe to be an expansion of the state sector and shrinkage of the private sector in the Chinese economy.

"I think there is a very amazing amount of bad analysis of China," said Lardy, picking up a pink clipping of a recent Financial Times article, which argues the Chinese state is still dominating everything.

According to Lardy's book, share of output by state-owned companies has dropped from 80 percent in 1978 to roughly 25 percent. And that includes the utilities, which are either highly regulated or state-owned in most countries. In China's manufacturing sector, the state-owned firms account for only 20 percent.

Lardy described state capitalism, a popular term for China in the Western news media, as a misnomer. "I don't think that evidence really supports that," he said.

In Lardy's views, China did try state capitalism, but it failed, and the areas where China had succeeded are where market forces were the strongest.

The economist believes even senior US officials, such as Treasury Secretary Jack Lew and US Trade Representative Michael Froman may not get a whole picture of the reality because the information they receive is often biased.

Lardy has talked to both Lew and Froman, but he admitted that they don't buy what he said. "Because all they talked to are firms having difficulties in China. And those difficulties are concentrated in services, where the state still has complete control," Lardy said.

"So they are the ones who go to USTR (US Trade Representative) and said we need this liberalization, but in manufacturing, they don't get any complaints. Manufacturing is pretty wide open," he said.

Early interest in China

A prolific writer on the Chinese economy, Lardy's office bookshelf contains some of the major books he has authored since the 1970s when he researched China's fiscal system of the 1950s for his PhD dissertation and many of the least popular books on China, the yearbooks on Chinese economics and finance in the past 28 years.

However, the economist got interested in China way before he studied Chinese economy in the 1960s as an undergraduate student in the University of Wisconsin at Madison.

Lardy's father, Henry Lardy, was a distinguished biochemist there until he passed away four years ago at the age of 92, having trained 64 graduate students, mentored 110 postdoctoral fellows and published more than 500 papers.

Lardy said he developed a small interest in China as a child in the 1950s when his father had some graduate students from Taiwan and he heard them talking about the crisis over Quemoy and Matsu (Jinmen and Mazu Islands) in the Taiwan Straits. He also heard people talking that John F. Kennedy would recognize China in the early 1960s.

"So I heard about China and I became interested in China very casually," Lardy recalled.

While Lardy enrolled as an economics major at the University of Wisconsin, he also started to learn Chinese, which he said was "because of his interest in China".

The Chinese language class had mostly students who were Chinese Americans whose parents wanted them to learn the language, and there were few Caucasians.

"So at that time, I decided to combine economics with my interest in China," he said.

When he became a graduate student at the University of Michigan, he took more Chinese language classes.

Alexander Eckstein, a leading economist on Chinese economy at that time, was teaching at Michigan.

Realizing that it was impossible to go to China at the time, Lardy spent much time in the Library of Congress going through various provincial papers from China in his research for his PhD paper on China's fiscal revenue sharing between the central and local governments. It later became his first book.

"There was a widespread thesis at that time that China was extremely decentralized in fiscal terms. Essentially I showed that was not quite true," he said of his first book.

Lardy taught at the economics department of Yale University soon after he finished his PhD in 1975. In 1978, he decided to go to Hong Kong to study Chinese at the Chinese University in Hong Kong and do research on Chinese agriculture. That became his second major book published in 1983.

In that book, Lardy looked into not just agricultural production, but also how agriculture supported the national economic growth, through the transfer of resources.

Unlike his first book which was about the transfer of resources geographically between provinces through the central government, the second book was about the transfer of resources from agriculture to industry.

He found that in Mao Zedong's time, the policy was unfavorable to agriculture, citing the prices farmers received in the procurement system.

"So it was industrialization based on exploitation of agriculture," Lardy said.

But he said that changed greatly after 1978 when farmers got a much better deal.

First trip

Lardy, however, might not realize that his first visit to China would be totally accidental. His wife, Barbara, who happened to know someone in the Hong Kong Family Planning Association which was leading a family planning delegation to the Chinese mainland in 1978, had already signed up for the trip. Five days before departure, someone dropped out and when his wife was asked if she knew somebody who wanted to go, she immediately said, "Yes, my husband."

Going on the heavily health-oriented trip with mostly doctors was not really Lardy's cup of tea, but he said it was interesting since he had never been to China, a place he now travels to several times a year.

He admitted that he never thought he would be able to go to China when he studied the Chinese economy in the 1960s. "Obviously I didn't anticipate there would be this big opening up in the late 1970s," he said.

After teaching at the University of Washington for 12 years, Lardy moved to the Brookings Institution in 1995, first as a visitor. But he said he liked being in Washington and his family liked it too.

Lardy resigned from the University of Washington to join the Brookings, where he wrote another two major books, one on China's financial reform, known in its Chinese version as China's unfinished economic reform and the other on China's entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO).

Sitting in his well-lit office with a big window at the Peterson Institute, Lardy can see his old office at the Brookings across the street.

He agreed that studying the Chinese economy was quite lonely in the early years and "you have to be very interested yourself".

When there were more people studying China, Lardy said they talked among themselves. "But now everybody is interested in China because China affects everything, globally," he said.

"Even people who have never been to China and don't know anything about China, they wanted to know more, they wanted to learn as much as they can, because the influence China has had on the global economy, commodities and everything else," he said.

"That has been a huge transformation," said Lardy, who has been sought after as a speaker on the Chinese economy by a numerous business groups, companies and conferences.

chenweihua@chinadailyusa.com

|

Nicholas Lardy, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, talks to China Daily in his office. Chen Weihua / China Daily |

(China Daily USA 08/29/2014 page10)

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

US, China to parley on extradition of criminals

US rice could see potential market in China

China accuses US over 'close-in reconnaissance'

EB-5 visa ceiling is short-term, expert says

China and US in talks on code of conduct

Chicken market gets a boost

Microsoft 'not fully open with sales data'

Lawmakers in move to tackle espionage threat

US Weekly

|

|