Providing charity not free

Updated: 2011-11-18 11:52

By Shi Yingying (China Daily European Weekly)

|

|||||||||

Dream vs reality

|

Friday was Jian Chuntian's last day at China-Dolls, the Beijing NGO that assists people with osteogenesis imperfecta, also called brittle-bone disease. It was also his last day in nonprofits since he started as a volunteer eight years ago.

Why drop out now? "I'm getting married," says Jian, who is 27.

His girlfriend is four years younger and a recent college graduate, so doesn't have much earning power now. Besides, he says, "My parents are old-fashioned and regard my job at an NGO as doing good deeds, but they can hardly understand it as a career. To quit this job is the hardest decision in my life.

"There's too much pressure. I need to buy an apartment in order to get married, and the wedding is costly as well. Many people have said I gave up my dream, but for me, the real dream is based on a foundation of reality."

Wang Yi'ou, the founder of China-Dolls, says, "Jian left without any request for a salary raise because he knew how much we could offer. We understood why he chose to leave."

Who will work

The wages that nonprofits are able to pay helps define their employees. Wang says that for organizations like hers, "We can't hire the best and brightest people when they can make more money in a for-profit business."

And women outnumber men, according to professionals at several grassroots NGOs. "For example, over 70 percent of my employees are female," says Liu Yonglong, secretary-general of Grassroots Community in Shanghai, whose services include free legal consulting. "That is probably because the man is born to support the family, under the traditional Chinese view."

Liu, 37, is an exception. He says he earned much more than his wife when he was an executive at a State-owned enterprise, "but now her salary is twice as much as mine."

He says his organization's average employee turnover has run as high as 100 percent in a year, mainly due to the poor pay. The seven full-time workers each take home about 2,000 yuan a month.

Liu's office shares its street address with a public toilet.

Mother's idea

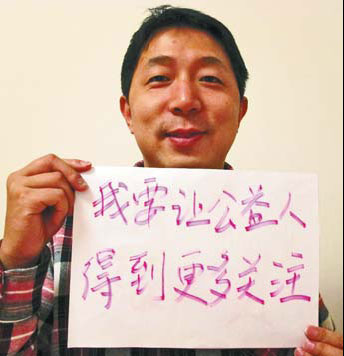

As for Xu Zhengjun, the idea of calling for an NGO strike came from a phone call from his mother in May. "She asked about my financial situation as usual, because both of my parents worried about it since my wife and I have devoted ourselves to NGOs," he says.

"At the end of that call, she says why don't you organize something like a union to improve NGOs' issue of low pay? All these young men working at grassroots NGO, they have family responsibilities, they need to support their parents and they need to save money to get married despite the poor pay. Why don't you do something to help?"

The idea grew from there, Xu says. He and his two colleagues "posted four wishes - our four most urgent requests - all over the Internet . . . starting a month ago. My four wishes are that I want better salaries, I wish to raise my employees' pay, I want more people to join us and I wish more attention from society."

People don't know

The day before Xu's strike, a panel discussion in East China's Hangzhou about NGO salaries attracted representatives of 15 local NGOs in person and more than 25 online from Beijing, Shanghai, Guangdong, Sichuan and Yunnan.

The local organizer, Wei Jun from Dishui Public Welfare Association, says he'd rather that the group's conclusion be presented as the cost of charity rather than a call for better pay.

"The general public doesn't have any idea what charity costs," Wei says. "They think it costs nothing - no human resources nor any transportation and fuel expense is involved - to do good. That's why we don't get paid well or don't get paid at all."

A simple example, he says, is sponsoring a poor child in Guizhou at school for one semester, with tuition of 300 yuan. "But it costs me another 50 yuan to send an employee to a remote spot to do the investigation, to see who needs help most. That's 350 yuan in total. The donors, however, refuse to give the extra 50 yuan as they think we're trying to make money out of this."

Wei says he used to spend his personal savings to cover expenses, "but it's not a long-term strategy because there's too much overspending. I spent my savings like water in the year of the Sichuan earthquake."