Portraits of change

Updated: 2011-12-02 09:00

By Raymond Zhou (China Daily)

|

|||||||||

|

|

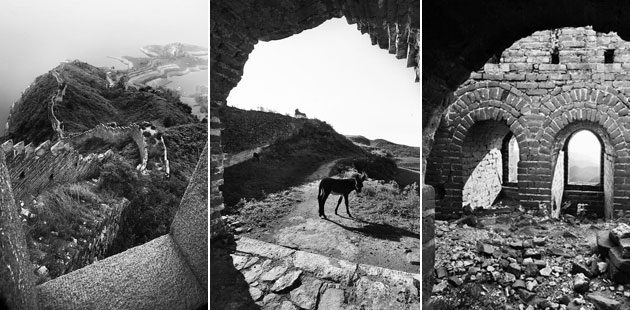

Moving the Steel Factory by Wang Yuwen, Our Stop in Thailand by Han Chao, Discolation by Luo Changwei. Photos Provided to China Daily |

|

|

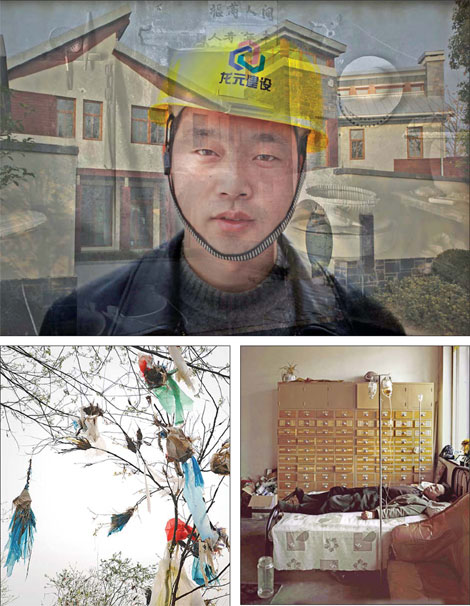

Clockwise from top: City Builders 1 by Jiang Jian, Life space by Qu Yan, Self-Created Landscape by Wang Peiquan. |

The art of photography in China is like wildflowers that blossom in the most unexpected - and somewhat remote - places.

That is, places like Lianzhou, about four hours' drive from the southern metropolis of Guangzhou, capital of Guangdong province.

Another photography exhibition I have attended is in Pingyao, a booming town in the height of the Qing Dynasty(1644-1911) and now a tourist Mecca known mostly for its well-preserved old town, especially the city walls, in Shanxi province.

It still beats me why hordes of art lovers from around the world take planes, trains and automobiles and trek for long hours to these annual events. But the panorama of imagery at the celebrations of the photographic art is certainly worth the effort.

Lianzhou is not as sprawling as Pingyao - I mean the photography shows, not the cities. But the more selective approach has yielded a heightened viewing experience, for which the theme running through the whole exhibition may well be more apparent.

Lianzhou Foto2011 is organized around the theme "Toward the Social Landscape", a concept with its roots in 1960s' US culture.

As with all things imported into China, this concept may have been embraced with different localizations. While running among the three exhibition areas, I could almost bet with fellow visitors that I could tell the age of a photographer by simply looking at the group of photos on display.

With a few exceptions, photographers middle-aged or older see themselves as chroniclers of social changes, while the young tend to look inward for inspiration.

As Duan Yuting, curator of the Lianzhou event, explains, "In recent decades, a large number of works from Chinese photographers tend to explore their inner worlds for personal expressions. And at the same time, others focus on the dramatic transformations of the landscape that result from upheavals of modernization and that turns photography into a crucial medium for broadcasting and analyzing the state of reality."

For Wang Yuwen, "social landscape" is the mammoth machinery in the rust belt that forms a chiaroscuro of decay.

These include images of the half crumbled manufacturing facilities; the walls with political slogans from a previous era still visible; workers riding bicycles home on a dusty road crisscrossed by ruts beneath and power lines above (it's a shot from above that shows their living environment); and, more ironically, a group of workers garbed like astronauts at a worksite that looks like an alien planet.

These photographs were taken when the so-called heavy industry base in China's Northeast was undergoing agonizing change in the 1990s.

Wang, now 63, says he felt it a mission to record these images of vanished industrial heft and is proud that the place has since bounced back.

Qu Yan, 56, presents a cluster of rural images that symbolize three "spaces" for many farmers: "life space" in dilapidated hospitals; "power space" where village chiefs hold powwows; and "spiritual space" for religious venues and consolations. The three are thematically interlinked and collectively paint a grim picture of today's rural existence.

Jiang Jian, 58, focuses his lens on the "city builders" - migrant workers who toil at construction sites. What makes his billboard-like blowups special is the juxtaposition of the workers and the edifices they erected, creating a fade-out effect as if the workers were ghosts who had to leave before the owners move in.

Many photographers have a keen eye for the seamy side of society.

Their relentless effort to spotlight doom and gloom bespeaks both their strong sense of social responsibility and the comparative latitude enjoyed by the nation's artists of photography vis-a-vis other forms of art.

Wang Peiquan stands out for turning ordinary eyesores into strangely beautiful visions. The objects of his camera are the plastic bags discarded by the roadside and stuck in trees. An epiphany dawned on him in March this year when he was on his way to attend a peach blossom festival.

"A forest of non-biodegradable plastic bags were swaying in the woods across a pond. They were swept down from upstream," he says.

"We hate this type of trash, but we contribute to it all the time. Now that the trash is hanging on trees, why can't we view it as a kind of objet d'art?"

Thus, he started his journey to shoot plastic bags that seemingly blossom out of tree branches.

"One day, when the trash flies into our living space or occupies urban skies, we'll be engulfed. Can you imagine such a prospect?"

On the other end of the photographic spectrum are pictures that are more reflections of the photographer's mind than what happens in the physical environment.

Perhaps "social landscape" can be twisted to refer to one's inner world, which, in any case, cannot be separated from happenings in the outside world. It could be for this reason that the English words "Toward the social landscape" are inversed in all promotional materials.

For 26-year-old Han Chao, his camera is a tool to record his love life and youthful angst.

"Under my lens, boys turn into men and lose their innocence," he says.

"They can no longer fritter away their youth but have to take up the burden placed on them by family and society."

These men are homosexuals forming a subculture rarely seen in the mainstream limelight. Some of the snapshots on display chronicle the days his gay lover, Dorian, spends with him.

Liu Wu, 27, found his inspiration on a trip back to his hometown in Shaanxi province. He took snapshots of his family members and relatives. These unvarnished faces reflect the erosion of time, but, "I feel I can see through their gazes into their hearts," he says.

"No matter how much the environment has changed, my early impressions of the place remain constant, and likewise, in the eyes of these people, I'm still that teenager they know."

Not all young photographers take the same approach toward their subject matter.

Some cannot resist the abundance of great materials emerging on the horizon.

Luo Changwei presents a spatial juxtaposition that is at once jarring and commonplace. In a series of photos titled Dislocation, he creates a sharp contrast by placing old architecture in the process of being bulldozed in the foreground and the gleaming high-rises that replace them in the background.

"Countless people see their living spaces irreversibly altered, and their morale and cultural continuity broken," the 29-year-old Guangzhou Daily photojournalist says.

"Scene after scene of demolition combine to highlight the cruelty of modernization."

In one of his photos, Luo managed to locate a family temple that is half buried in a pile of rubble. The symbolic significance is loud and clear - that China's tradition is being sacrificed in the name of economic growth.

Except in historical photos, images of happiness are rare in this or other photography shows.

A few ad-hoc galleries in the downtown square and the city culture center, which are not part of the official Lianzhou Foto2011 exhibits, feature picturesque sceneries and people totally devoid of anxiety or despair.

Such tourism-tinted parades of natural or human beauty are the mainstay of employer-organized photo exhibitions for shutterbugs across the country.

This dichotomy of photography as a contrivance for tourism promotion and photography as a platform for social criticism is amply illustrated in the Lianzhou exhibition.

The images on the walls stand in contrast with the natural environment of the city, which is surrounded by karst mountains.