Guardian of the bund

Updated: 2012-01-27 07:28

By Shi Yingying (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

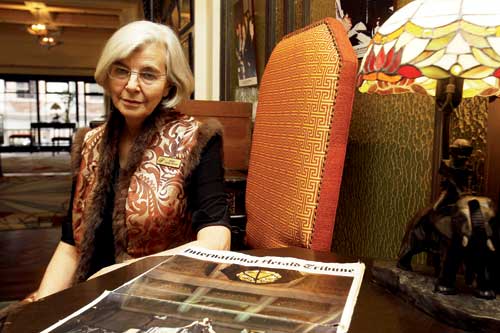

Jenny Laing-Peach sits in the Peace Hotel's Peace Gallery, which she is in charge of. For this Australian woman, Shanghai is a familiar place of family roots and culture as four generations of her family have worked on the Bund. Yong Kai / China Daily |

SHANGHAI - She knows every story behind each building along the 2-km stretch of the Bund built during the last century. Despite her age of 67, she can climb up to the top of the Peace Hotel to point out exactly where these stories happened. Four generations of her family, from her grandfather to her son, have worked on the Bund, says historian Jenny Laing-Peach.

To this Australian woman, Shanghai is a familiar place of family roots and culture, even though she was born, educated and worked in Sydney for the first half of her life.

"I'm the third generation of my family to work as an executive on the Bund," says Laing-Peach, who came to Shanghai in 2000.

"My grandfather worked in the Customs House during the 1890s and my father worked for a shipping insurance firm. It was in No 18 on the Bund, which now turned into Bund 18 (where Cartier and Zegna now sit) - that was his office on the second floor."

"One of my sons has been restaurant manager of M on the Bund and I work here," says the in-house historian for Fairmont Peace Hotel, the 82-year-old symbol of the Bund.

"I don't know if there are very many complete Chinese families who can do four generations on the Bund."

Although Laing-Peach got her Irish face from her mother, her enthusiasm for Shanghai came from her father, who was half-Chinese.

"My grandmother was Shanghainese and I could speak Shanghainese before I could speak English," she says. "It is a shame that I can't remember now."

Laing-Peach says she migrated to Australia with her parents during World War II.

"My father, like many people after the war, died of displacement - like a broken heart, even he managed to immigrate to Australia."

"He knew he would never come back to China (for political reasons) because by then (1940s and 1950s) it was particularly difficult for those China-born with foreign wives to return to China," says Laing-Peach.

"The rest of the world was very isolated of China (during the '50s). There was no news from China - I remember we could only get news in English from Hong Kong."

"I also remember our garden in Sydney has been unusual - we always had those plants and flowers that were different to other people's - and I didn't know why. But as soon as I came here I understood, what my father was doing was building a beautiful Chinese garden," she says.

Having lived with her husband, journalist Barry Porter, in Shanghai for 11 years, Laing-Peach said her return to Shanghai was a must.

"I came here because this was my parents, uncle and auntie's home, this was what they talked about all days when they got to go to another country, where they didn't choose to go," she says.

"I knew the map of Shanghai when I came here, often by old, non-Chinese names, and I knew exactly where to go."

"I felt instantly a sense of belonging."

With years of teaching drama in Sydney, Laing-Peach quickly found herself a job as a professor in Shanghai.

"I worked at Shanghai University for eight years and I lectured in English, particularly in theater and drama," she says.

"I wrote a course called Shakespeare with Chinese Characteristics and we did A Midsummer Night's Dream, where all the fairies were done in Peking Opera style, for one semester."

"The pink-eye make up, costume and the singing style were all from Peking Opera. The performers were singing in both languages - English and Chinese - because who knows what language fairies speak," jokes Laing-Peach, adding that the play was staged in the Shanghai Dramatic Arts Center.

Besides playing the role of theater director and teacher, she has also been involved in many culture- exchange events, such as the annual James Joyce "Bloomsday Shanghai" celebration. Laing-Peach co-founded the Shanghai International Literary Festival, where she wrote and published articles on the greatest historical figures of Shanghai, such as the renowned writer Lu Xun and the first mayor of Shanghai, Chen Yi.

Starting in 2010, when the Peace Hotel - the green copper pyramid landmark of Shanghai - returned to the Bund after a three-year renovation, Laing-Peach became the legendary hotel's in-house historian. She's now in charge of the Peace Gallery, which showcases an almost 80-piece collection, ranging from antique tableware to crystal that decorated the hotel's old rooms. There is also a heritage salon and afternoon tea reading that usually features themes of Chinese literature and culture as well as a historical tour of the hotel and the Bund.

In Laing-Peach's eyes, the image of the port city of Shanghai is exactly like Peace Hotel's octagonal-shaped atrium at the grand entrance - with many points of entry allowing for not only exchanging commodities but ideas.

"It was no accident that jazz, film, the new way of writing (meaning left-wing writers such as Lu Xun), the new political theory and the communists' first meeting place all happened in Shanghai," she says.

"Through all eight points of octagon, they all come to the middle," she says. From there, "Some go straight, some meet another line and go in a different direction. By meeting another line, they form a different shape - it's like people' lives being transformed by the experiences being in this extraordinary city."

"Somebody once told me during the tour of Peace Hotel that 'You're a born storyteller'. I never thought that way," she says, "but I know one thing for sure - stories should be told. And I love sharing what I know about."

'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Health new priority for quake zone

Xi meets US top military officer

Japan's boats driven out of Diaoyu

China mulls online shopping legislation

Bird flu death toll rises to 22

Putin appoints new ambassador to China

Japanese ships blocked from Diaoyu Islands

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

US Weekly

|

|