Singing magnet

Updated: 2012-06-09 07:31

By Raymond Zhou (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

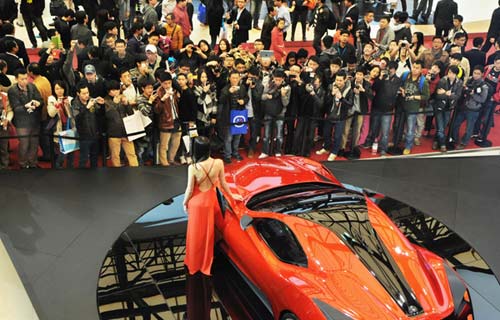

Placido Domingo presides over the 20th edition of Operalia, the World Opera Competition, at the National Center for the Performing Arts in Beijing. Provided to China Daily |

Placido Domingo has sung more roles than any other tenor in history. The towering figure from the operatic world offers his views on music from many cultures and reveals the secret to the longevity of his career.

Where Placido Domingo goes, the world of opera tilts slightly to that place. The weight he carries and the charm he exudes are such that the opera-loving public naturally gravitates towards him. Judging from the thunderous applause that greeted him from the opera house of the National Center for the Performing Arts (NCPA) in Beijing on June 7, this is no exaggeration.

The Spanish tenor was not even singing. He was just presiding over the semifinal of a singing competition.

The event is the 20th edition of Operalia, the World Opera Competition he founded in 1993, which has so far catapulted many young singers into stardom, including He Hui, a Chinese soprano who is now very active on some of the world's most prestigious stages, and Liao Changyong and Sun Xiuwei, who are pillars of the emerging edifice of operatic China.

Apart from his consummate artistry, Domingo is known for his generosity towards young singers at the start of their careers. He designed this competition mainly to maximize the exposure for young talents, aged 18 to 32, who struggle to break through to the cutthroat field of professional opera.

To achieve that, he invites mostly artistic directors and managers of opera houses worldwide who are responsible for casting. Domingo does not vote for the winners, but he often invites them to sing in productions where he has influence. This is considered by some to be more important than a prize because it can be a much sought-after break for a youngster.

Chinese soprano Sun Xiuwei recalls with emotion how Domingo advised her on the choice of repertory for the competition, and after winning third place in 1997, invited her to sing in Washington DC and Los Angeles, where the maestro managed the local opera houses.

"He always lavishes praise on you and does not hide his feelings when he is touched by your singing," Sun says.

In an exclusive interview, I asked him whether he viewed China as the next big market for opera and a new source of opera talent. He said "Both". He has discovered wonderful singers from China, and also from South Korea and Japan. On the global stage, they have to compete on an equal footing with singers from other countries, mastering the nuances of foreign languages, stage movements and myriad other skills.

In the past few years, the superstar from classical music has made several trips to China, singing with Chinese folk singer Song Zuying and first taking on the baritone role in Verdi's Rigoletto at Beijing's Reignwood Theater. When asked how a singer can reconcile his or her country's traditional way of singing and Western operatic singing, Domingo commended the original Chinese-themed operas commissioned by the NCPA, saying that foreign artists can also participate as long as they master the Chinese language.

"What about Peking Opera? Is it possible for a non-Chinese to sing it?" I asked, thinking of the zarzuela section in Operalia, a form of Spanish music akin to opera. The maestro told me that he had indeed seen this quintessential Chinese art form, but it uses a different musical idiom and takes a long time to grasp for outsiders. But theoretically, it should be possible.

There are people in China who believe Peking Opera should be translated as "Jingju", just like kabuki or zarzuela for that matter. "Is the English term 'Peking Opera' appropriate?" I asked. According to Domingo, it can indeed be called "opera" because it applies singing throughout.

He also feels that Chinese folk singing can be incorporated into dramatic situations of the traditional opera, but like Puccini who used several Chinese folk songs in Turandot, it may take an outsider to use it ingeniously and find a worldwide audience.

When talking about China's notorious Qin Shihuang, or First Emperor Qin, a role specifically written for him by Chinese composer Tan Dun, Domingo was very philosophical and touched on the complexities of the character. He cautioned we should not judge historical characters by current standards, and compared the character to the title character in Handel's Tamerlano, who was similarly controversial in history.

Domingo has played such a rich and diverse array of characters and with such dramatic conviction that he has been called "a singing actor". As his vocal timbre darkens, he moves effortlessly into the baritone repertory, gaining a new wealth of wonderful roles.

Decades ago, he mentioned he would sing the role of Don Giovanni. That dream is still with him, he said. But he will not do the role on stage partly because the lack of moral fiber of the character is not something he admires.

In a career that spans 53 years, Domingo has sung a total of 139 roles - and growing every year, a number unmatched by any other tenor in history. It has been made possible by a combination of calculated adventurousness and prescient planning. He explained that he did not take on the role of Tristan on stage because he was afraid it would damage his voice and cut short his career. (He recorded the complete opera in 2005, turning it into a milestone as it was widely seen as a swan song to studio recordings of complete operas - an expensive undertaking no longer feasible in this age of downloads and diminished budgets.)

Domingo considers himself lucky to straddle the eras of studio recordings and then video recordings. The previous generation, like Callas, did not leave too much video chronicling of their performances, he said. He remembers the first time he came to China he was surprised so many people were already familiar with his singing. "Twenty years from now, people may not know who I am - if not for the recordings."

Domingo devoted a significant part of the past two decades to Wagner, a repertory in which many at first doubted he would excel. He won the skeptics over with one role at a time. By the 2005 Tristan und Isolde recording, it was quite clear he has absolutely nothing more to prove. Yes, his only brush with Siegfried, a notoriously arduous and lengthy role that threatens to kill any healthy career, was a disk of selections from the last two operas of Wagner's Ring Cycle. But he said he has not given up on Loge yet, a very unique part in Das Rheingold, the first of the four operas.

Opera fans in China can expect to hear the super-tenor in a complete and possibly new role on the stage of NCPA. But he would not divulge what it would be, saying that courtesy dictates that he should leave it to NCPA to make the announcement.

Meanwhile, he is to conduct the NCPA Concert Hall Orchestra in Sunday night's final round of the Operalia competition. Perhaps years from now, when some of these young singers become superstars in their own right, they will reminisce how much they benefited from this experience and what it means to be aided and encouraged by an esteemed giant of an older generation.

For a country where Western-style opera is still a curiosity more than a lifestyle, Domingo's presence adds much needed glitter and brings out the horde of rapturous fans who will probably be braver in spreading the gospel of great music.

Contact the writer at raymondzhou@chinadaily.com.cn.

'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

'Taken 2' grabs movie box office crown

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Rihanna's 'Diamonds' tops UK pop chart

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Fans get look at vintage Rolling Stones

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Celebrities attend Power of Women event

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Ang Lee breaks 'every rule' to make unlikely new Life of Pi film

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

Rihanna almost thrown out of nightclub

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Dark Knight' wins weekend box office

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

'Total Recall' stars gather in Beverly Hills

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Health new priority for quake zone

Xi meets US top military officer

Japan's boats driven out of Diaoyu

China mulls online shopping legislation

Bird flu death toll rises to 22

Putin appoints new ambassador to China

Japanese ships blocked from Diaoyu Islands

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

US Weekly

|

|