China's economy continues its transition

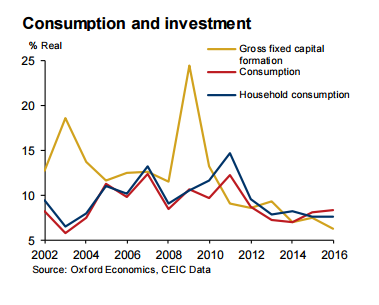

Having said this, fixed investment remains very high at a bit under 43 percent of GDP last year – down 1 ppt from 2015, we estimate – leading to a rise in the capital stock of 9 percent and a further nudge up in the capital/output ratio to 3.3 (in prices of 2010). While continued capital deepening helps raise the economy’s productive capacity and labor productivity – which was up 6.5 percent in 2016 – it also increases the risk of over-investment and puts pressure on rates of return. Indeed, reducing excess capacity in heavy industry remains a key challenge in 2017. Moreover, the rapid credit growth associated with high investment is not sustainable and will eventually have to be reined in. The (mild) change in tone on the macroeconomic policy stance for 2017 is in recognition of that fact.

Overall employment rose only 0.2 percent and should soon turn negative as demographic pressures are a drag on the working age population. However, the real action on China’s labor market is on the rural-urban nexus. The pace of urban job growth continued to ease in 2016, to 2.5 percent. But the secular rise in the level of urban employment means that, in terms of the number of people or as a share of total employment, the slowdown is quite mild (Chart 2). The same is true if we look at the population data (instead of employment). As a result, the urbanization rate has continued to rise steadily by a bit more than 1 ppt per year, reaching 57.3 percent in 2016 (from 44.3 percent 10 years ago).

In other words, in terms of the impact on the overall economy and transition, the pace of urbanization has not slowed much in recent years. This matters since urbanization is key to rebalancing, as it boosts the services sector and consumption.