New Hohhot park highlights traditions

Updated: 2015-09-14 08:22

By Xu Lin and Yuan Hui(China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

|

The newly opened Dashengkui Cultural Creativity Industrial Park in Hohhot. [Photo by Feng Yongbin/China Daily] |

Traders rode camels carrying silk and brick tea over the Yinshan Mountains, arriving in Ulan Bator and finally Russia. They also sold sheep and horses to other areas of China.

The company had more than 8,000 employees and 20,000 camels, and an annual trade volume of 500 tons silver in its heyday. An old saying goes that Dashengkui's wealth equaled half of Hohhot's.

The company's business began to decline in the 1920s, following Outer Mongolia's independence and the issuance of Soviet rubles after the October Revolution.

"The travelers caravanned along a route that's like an extension of the Silk Road that transported Chinese goods abroad," Dashengkui Museum's head Zhang Shufan says.

"Dashengkui boosted China's economic development and promoted cultural exchanges between the Han and other ethnic groups. It had enhanced national integration and unity. It's the best place to know about Hohhot."

The policy allowing artisans to work in free spaces for three years not only benefits travelers but also endangered forms of cultural heritage, such as ethnic Hezhe fish-skin clothing, Li says.

"It's a good platform to promote our longstanding ethnic culture," says 42-year-old Gao Jinzhu, who recently opened a matouqin studio in the park. The horse-head fiddle is a traditional Mongolian two-stringed instrument. It's a traditional accompaniment for the ethnic group's folk music and often provides the background sound for Mongolian throat singing, in which a single vocalist seems to produce two voices simultaneously.

"Every craftsperson can exhibit his own understanding of ethnic identity through art."

Gao left a steady bank job to make matouqin because he couldn't stand working a 9-to-5 gig. He enjoys the freedom his new livelihood affords, he says.

He typically spends two or three years making each instrument to give the wood time to season. Matouqin that are mass-produced on assembly lines are typically made with unseasoned wood, which lowers their quality, in addition to ignoring the cultural spirit of their manufacture.

While waiting, he lets the wood "listen" to different genres of music from his cellphone or music players. He believes the wood would actually listen to the music like human beings, and he thinks it's better for the wood.

- Russian military experts present in Syria

- Norway PM says Norwegian citizen taken hostage in Syria

- Hungarian TV journalist fired for tripping up fleeing migrants

- Leaders from EU, Russia, Ukraine to meet in Paris in Oct

- Music is food for the soul for young Chinese violinist

- Australia's Tasmania, China agree to 'work together' on Antarctic expeditions

Americans mark the 14th anniversary of 9/11 attacks

Americans mark the 14th anniversary of 9/11 attacks

7 ways Chinese travelers benefit from the US visa extension

7 ways Chinese travelers benefit from the US visa extension

In pictures: School life from the lens of sports teacher

In pictures: School life from the lens of sports teacher

Ten treasures from Palace Museum to look forward to

Ten treasures from Palace Museum to look forward to

Top 10 richest Chinese tech giants

Top 10 richest Chinese tech giants

10 years of Sino-US exhibitions

10 years of Sino-US exhibitions

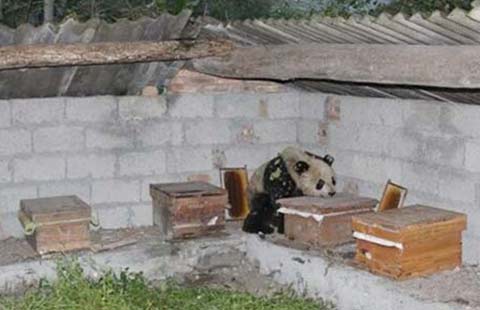

Greedy panda eats ten boxes of honey

Greedy panda eats ten boxes of honey

Soldiers in Sansha guard the islands

Soldiers in Sansha guard the islands

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Over 14,500 Chinese pilgrims in Mecca

Xi's trip to US to 'chart course' for ties

US to accept 10,000 Syrian refugees, says White House

WWII veterans awarded medals for victory efforts

LA still a top destination for tourists even as China's economy slows

New iPhones unveiled

Inside look at Apple's newly-launched products

Peking Opera performance thrills NY

US Weekly

|

|