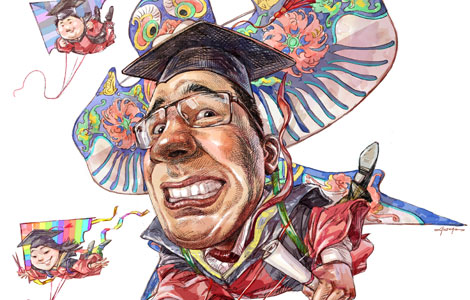

In schooling, China and the US can learn from each other

Updated: 2013-10-30 03:48

By KELLY CHUNG DAWSON in New York (China Daily)

|

||||||||

China's economic rise has inspired a fair share of hand-wringing about how America might better train new generations for global competition, with a particular focus on parenting and education. Although author and educator Nancy Pine stops short of Tiger Mother-style repudiation of American child-rearing in her new book Educating Young Giants, she does raise a few questions about what Chinese schools have to offer.

For one, elementary-level Chinese textbooks are more likely to delve deeper into complex subjects, she writes. A lesson in literature might discuss the use of foreshadowing in fiction, for example.

In China, educators are more likely to teach in the style of a performance, adhering to scripted lesson plans. Chinese teachers ask questions and students answer according to their reading; in the US, students are encouraged to ask questions or suggest occasionally half-baked answers that are neither correct nor incorrect but aimed toward the greater goal of stimulating group discussion. As Pine quotes the parent of a Chinese student: "A Chinese teacher would never ask, ‘What do you think?'"

In the US, elementary-school students are more likely to sit in a circle or in L-shaped formation around which a teacher will move regularly; Chinese students generally sit in rows, with the teacher planted at the front at the classroom.

Most notably, Chinese students learn math conceptually rather than through the simple repetition of arithmetic processes, with mathematical concepts introduced with small numbers and then expanded to numbers in the hundreds of thousands, Pine writes.

In 2010, students in Shanghai joined the international standardized testing system for the first time when the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development introduced the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA). The Chinese students far outscored peers all over the world in almost every subject. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan told the New York Times that the scores should be viewed as a "wake-up call" for American educators.

But China still yearns for its own Steve Jobs, and the puzzle of inspiring innovation in a culture that has long heralded imitation continues to present a challenge.

"Fundamentally, both countries want what the other has," Pine said. "Americans want academically focused kids who excel in math, and Chinese want kids who know how to ask questions and are innovative like Americans."

At a recent discussion of the book at New York's China Institute, Pine declined to speak about the drawbacks or long-term negative effects of each system. But in a room full of American educators, it seemed a given that "strict" or "rigid" classrooms were the enemy. The use of collaborative, improvisational activities involving group learning was presented as the obvious goal, seemingly necessary for the development of healthy students.

Pine naturally operates from a Western perspective, and has made it clear that she doesn't intend for Educating Young Giants to be divisive or controversial. She simply presents observations gleaned from 20 years in the US school system and from various stints teaching English in China.

Pen-Pen Chen, a language pathologist and teacher who works with young Chinese immigrants in New York, notes that individualistic cultures are naturally inclined to view collectivistic attitudes that promote the opinion of the "whole" as negative.

"Thousands of years of tradition in China have stressed the value of the community and the family before the individual," she said. "While there's nothing inherently wrong with that, the reality is that Chinese students often have no idea how they actually feel about a subject."

In the US, students are more likely to learn a subject by "doing" rather than being told, she said. In that context, every student might walk away with a different answer.

"In China, you're more likely to have a collective, cohesive opinion about history, for example," she said. "This makes it easier to make statements like ‘Chinese people think this way', whereas in the US it's harder to make blanket statements about the way American people think. In the end, maybe the Chinese method does actually get you to the goal easier and more efficiently, because it gets the job done without a lot of dissent."

As long as American institutions like Harvard and Yale remain at the top of the education totem pole worldwide, Chinese students will continue to strive toward American standards. However, to attain top scores within the Chinese education system, students must conform to a system that Chen compares to a single bridge upon which only one in 1,000 succeeds. In the US, there are a thousand paths to success, although the most obvious ones still involve top universities, she said.

The US and Chinese education systems can't simply "copy" one another, Pine argues.

"We need to understand what we each do well and adopt the best practices for our schools," she writes in press materials. "There's nothing more important than the best education for our future generations. We can learn from the Chinese, and they can learn from us."

kdawson@chinadailyusa.com

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Boston victim's scholarship fund reaches $1m

Beckham picks Miami for MLS franchise

UN urges end of US embargo on Cuba

IMAX: Coming to a home near you

SUNY recruits students in China

NSA denies reports on US spying in Europe

US approves chemical probes against China

China and the US can learn from each other

US Weekly

|

|