Sands of time

Updated: 2011-09-30 09:19

By Lu Chang (China Daily)

|

|||||||||

|

|

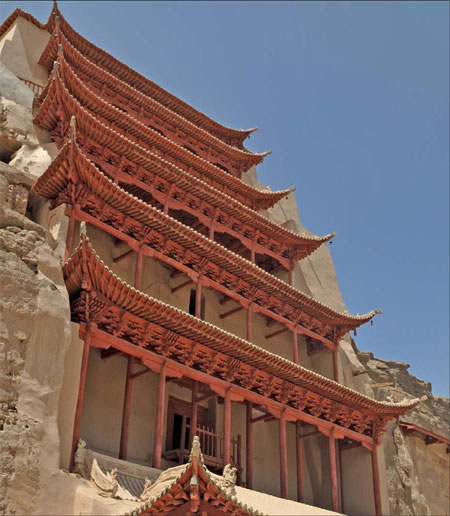

For more than a thousand years the Dunhuang Mogao Grottoes have withstood the ravages of time. But the timeless treasures are now facing their biggest challenge with undue human attention threatening their very existence. While vandalism, theft and sale of cultural relics are constant threats, the stream of humanity is the most dangerous challenge confronting the Grottoes, a cultural heritage site that features on the United Nations Education, Science and Culture Organization list.

| ||||

The number of tourists visiting the Mogao Grottoes has increased by a huge margin in recent years. It is expected to hit 650,000 this year, an increase of about 100,000 compared with last year, according to Dunhuang Academy, which is in charge of research, conservation and tourism at the site.

To slow the influx of visitors to the ancient site, the Dunhuang Academy has invested nearly 265 million yuan ($41 million) for a multimedia conservation project. The project involves using digital technologies to upgrade conservation efforts, including controlling tourist numbers, monitoring the temperature and humidity in the caves, apart from a new museum and visitor center.

Located 15 kilometers north of the Mogao caves, the visitor center, spread over 40,000 square meters, is likely to be completed by 2013. It features an interactive, documentary screening room and high-fidelity duplications of the caves with a tourist reception hall, a multimedia display area, a digital theater, a dome theater, restaurants, shopping area and other facilities.

Song Ming, head of the new center, says the center will allow visitors to experience the caves in 360-degree views inside the dome theater, which can zoom in on any particular feature.

"Visitors can see the mural images and learn something of the history, art and culture before having the opportunity to visit the caves. This will reduce the time visitors spend in the caves and improve the reception capability of Dunhuang," he says.

|

Of the more than 700 caves in Dunhuang, only a few are open for public viewing.

"Fragile sites like the cave temples of Mogao can suffer from overuse by visitors," says Neville Agnew, a senior specialist of the Getty Conservation Institute in Los Angeles. "Not only can crowding in the caves impact the paintings, but also lead to an unsatisfactory experience for the visitors themselves."

Research conducted by Dunhuang Academy shows that when 40 people stay in a cave for half an hour, the temperature rises by four degrees, while the content of carbon dioxide increases five times and humidity grows by an extra 10 percent. As temperature and humidity in the cave changes due to the moisture from the breath of visiting crowds, salt in the grottoes dissolves and crystallizes. This repeated contracting and expanding causes large pieces of the plaster from paintings to fall off.

Of the 735 caves, 492 are filled with exquisite paper-thin skin wall paintings that span 46,000 square meters of wall space, some 40 times the size of the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican.

Tech major Microsoft Corp has helped in the conservation of the UNESCO site with the donation of a video camera, which has a resolution of 1.3 billion pixels, to the Dunhuang Academy in August.

Scientists from Microsoft Research Asia and Dunhuang Academy started to work together to develop the camera in 2010, so that even very fine details of the grottoes and murals can be recorded and stored. The academy plans to digitize 147 grottoes by 2015.

The grottoes, once a capsule on the Silk Road, where the East met the West, have been subjected to various kinds of damage, from the long-term erosion of wind-blown sand and the encroaching desert, to occasional flooding and earthquakes.

But today the East and the West are converging on Dunhuang again, this time to help ensure the survival of a global heritage site. It is a cultural collaboration that echoes the glorious history of the caves. Scholars from across Asia, Europe, the United States and Australia are working to ensure that the glories will never again be buried in the sand.

Agnew and his team from Getty are part of these efforts. When he came to Dunhuang, wind-blown sand was a major problem as it was difficult to isolate the conglomerate rock half-buried in the sand.

"When I came here, there were many problems to be faced in conservation of wall paintings, management of the site, dealing with physical threats like wind-blown sand, environmental monitoring of conditions at the site, scientific investigation of the causes of deterioration and so forth," Agnew says. "But the biggest challenge from a technical conservation point of view at Dunhuang was to identify the reasons for the deterioration of the wall paintings."

The amount of sand in the grottoes region accumulated to about 3,000 to 4,000 cubic meters annually. Wang Xudong, deputy director of the Dunhuang Academy, says the nearest floating desert dune is only 5 km away from Dunhuang, and still expanding in all directions. "If sand from the dune sweeps into the grottoes, rock facades will give way, leaving all the interiors exposed," Wang says.

But through years of research, analysis, monitoring and serious measures, three belts to prevent sand from blowing have been built on the floating dune, including an angled wind barrier and a 20-hectare grass patch, two 2-kilometer forest shelter belts and a nylon fence. The amount of sand has dropped by more than 90 percent now.

In 1998, the Dunhuang Academy initiated a joint project with Getty in Cave 85 and used it as a model site for future wall painting conservation. The murals in Cave 85, painted in AD 868 with mineral and plant pigments illustrating everyday life during the Tang Dynasty, suffer from many of the typical problems found throughout the site.

"Unlike the typical frescoes of Europe, which are more robust, and based on limestone, the wall paintings at Dunhuang and at many other sites on the Silk Road are applied to a clay base on the rock surface," says the 72-year old Agnew. "Years passed. The mud dried and shrank, creating hollows between paints and the rock beneath. Paintings, therefore, came to be suspended on the wall, in a ramshackle fashion."

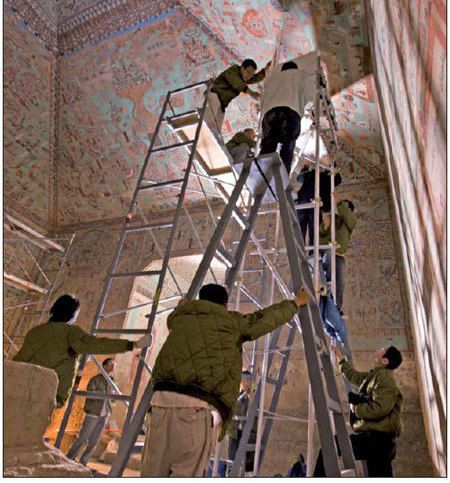

Su Bomin, the head of the Conservation Institute of Dunhuang Academy, says it took the team almost eight years to devise a special grout to reattach mural segments that had separated from the rock face.

Instead of jumping into some rescue work, the Getty Conservation Institute and academy conservationists adopted a more sustainable approach to find the right material to fill into the hollows between the paint and the wall after analyzing the paint, the rocks and the salt.

"We used to rely on experience to rescue these flaking paintings," says Su. "But working with the foreign experts allowed us to jointly develop safe methodologies and a scientific solution for conserving the wall paintings not only in cave 85 but also in other sites."

The Mogao Grottoes' success in conservation has helped China make considerable strides in cultural relic security, environmental supervision and grotto management. "It is a model for the efficient conservation and reasonable use of Chinese cultural relics," says Wang Xudong, deputy director of the Dunhuang Academy.

"But the conservation work needs long and deep commitment and no one can succeed alone. The scale of the site is so large that it requires efforts of several generations."