BRIC layer proud of his work

Updated: 2012-02-03 07:43

By Cecily Liu and Li Fangchao (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

Jim O'Neill believes the biggest challenge for the Chinese economy is to make a structural shift from investment and export-led growth to focus on domestic consumption. [Provided to China Daily] |

Economist sees future and leaves mark on language

The BRIC economies' spectacular growth is a miracle of the last decade. It has fundamentally transformed both the way investors see the world and the career of Jim O'Neill, former chief economist for Goldman Sachs who coined the acronym for Brazil, Russia, India and China 10 years ago.

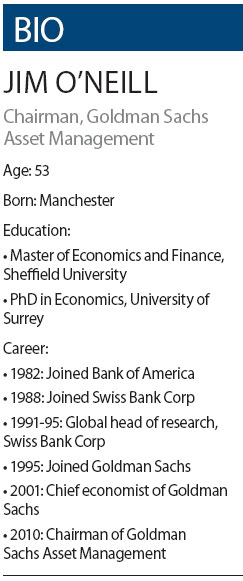

"I'm both pleased and shocked that it has become such a big thing. Obviously it's a great privilege," says O'Neill, now chairman of Goldman's asset management arm.

In November 2001, O'Neill boldly predicted that in a decade the BRIC countries' combined share of global GDP could rise from the then 8 percent to about 14 percent, and China alone might get close to the size of Germany.

In the event, the BRIC countries' share of global GDP has risen to about 18-19 percent. The collective nominal growth of the BRIC economies was close to $10 trillion, more than tripling their 2001 size of about $3 trillion. More strikingly, China has sailed past Japan and already become not far off twice the size of Germany.

Time has proved O'Neill's past critics wrong. Moreover, it has made BRIC a near ubiquitous financial term, shaping how a generation of investors, financiers and policymakers view the emerging markets: companies ranging from Nissan to WPP have developed BRIC business strategies; several dozen financial institutions now run BRIC funds and business schools have launched BRIC courses.

As the acronym's influence spread, O'Neill received a nickname, Mr BRIC, which he finds amusing.

|

|

The four BRIC countries are separated geographically and culturally, but O'Neill zoomed in on their shared large population, underdeveloped economies and a willingness to embrace other economies' cultures and markets.

O'Neill grew up in south Manchester, and was the son of a postman. "Down the road I lived on, one side was really poor, the other side was quite wealthy, and I went to school in the poor side," O'Neill recalls, speculating his need to relate to different classes of people at a young age later helped him to think outside the box of conventional Western wisdom.

To commemorate the 10th anniversary of the coining of the BRIC acronym, O'Neill published his book The Growth Map: Economic Opportunity in the BRICs and Beyond, a fleshed-out version of the already famous story, for which he says an alternative title could be "Travels of Mr and Mrs BRIC".

In retrospect, O'Neill admits that he was not bold enough in his predictions. "Ten years is a long time, and I wanted to be deliberately cautious," he says, adding that he is applying the same cautiousness to the BRICs' next decade of growth, with China's annual growth estimated at 7.5 percent.

O'Neill first came to China in 1990, and since then has returned every year for work and on holiday. He has witnessed a country undergo profound transformations, but sums up China's biggest change thus: it now has "traffic jams instead of bicycle jams".

On China, the country he considers "the most important one" of the BRICs, O'Neill is optimistic.

He says there is "no bubble" in China's property sector, arguing that because the country is only 50 percent urbanized, demand for houses in cities will not slow and prices will not significantly drop. "This is a big fundamental thing which Western people, still observers, misunderstand."

China's inflation is also increasingly hard to control. Last year inflation was 5.4 percent, well above the government target of 4 percent.

But O'Neill believes last month's inflation rate of 4.1 percent compared with 6.8 percent in May shows that policy makers have done a very good job.

He says the biggest challenge is to make a structural shift from investment and export-led growth to focus on domestic consumption, but believes this change is already taking place. Citing stronger-than-expected fourth-quarter GDP of 8.9 percent last year and the country's weak export growth over the same period as evidence, he says: "That must mean something else has taken (exports') place."

O'Neill says "the days of China growing more than 10 percent are already finished", and it is moving toward more sustainable growth.

Asked where his optimism comes from, O'Neill says: "Every Chinese policymaker I met is always worried. Things go wrong when people don't worry." He cites the 2007-08 US property bubble as a key example.

O'Neill's BRIC story initially drew inspiration from the terrorist attacks of Sept 11, 2001. The horrific reality in Manhattan exposed the dangers of a Western-centric view and unleashed a cascade of thoughts that were already accumulating in his mind.

Two months later, he scoured the globe and fixed his interest on four countries that bore much more growth potential than traditional emerging markets: Brazil, India, Russia, and China, and wrote about them in the Goldman Sachs paper "Building Better Global Economic BRICs."

But the acronym really took off in 2003 with his colleagues' paper "Dreaming with BRICs: The Path to 2050".

This time O'Neill's team predicted that China's economy would become as big as that of the US by 2027, while the total GDP of the BRIC nations would overtake the six largest Western economies in 2032 - compared to 2039 in his 2001 prediction.

O'Neill says his team got lucky. He recalls: "We happened to coincide with what many international companies were starting to realize themselves. So when we wrote more and more research on it, more and more international companies were like, 'Wow, this is what we smell.'"

Within days Goldman economists were flooded with e-mails from executives at companies ranging from the mobile telecoms group Vodafone to the miner BHP Billiton to Ikea and Nissan.

BRICs suddenly provided executives with a snappy way of discussing strategy they were already implementing.

Another major consequence of the BRIC story that followed was the desire of other large-population emerging economies to get into the "club".

Alternative acronyms like Bricks (with South Korea included), or Abrimcks (chucking in the Arab region and South Africa) are frequently suggested to him.

O'Neill says that the BRIC label "certainly helps the perception that (a country) is special".

He also seems to be enjoying his authority as the one who creates such labels. "I've just been invited to a Mexican dinner, and I know it's linked to 'Why don't you call it BRIMC?'"

But great power comes with great responsibility, and fear of the BRIC economies failing to achieve their potential frequently worries him.

But for now, O'Neill accepts his role, "I've created this thing, and I've become associated with it, so I guess it will stick with me for a long time".

Relief reaches isolated village

Relief reaches isolated village

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Earth Day marked around the world

Earth Day marked around the world

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Chinese fleet drives out Japan's boats from Diaoyu

Health new priority for quake zone

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

Russia criticizes US reports on human rights

China, ROK criticize visits to shrine

Sino-US shared interests emphasized

China 'aims to share its dream with world'

Chinese president appoints 5 new ambassadors

US Weekly

|

|