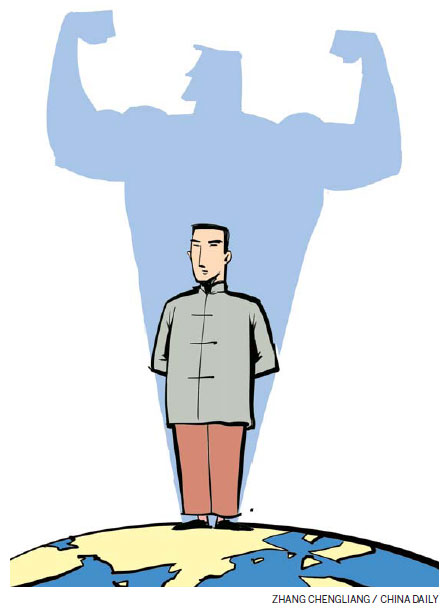

China's superpower coronation is still some way off

Updated: 2012-04-06 08:44

By Hu Yifan (China Daily)

|

||||||||

In the aftermath of the global financial crisis, and in the course of the continuing European sovereign debt crisis, large developed economies have struggled to regain growth momentum, while China has continued to grow at a robust pace. This has led to speculation of a concurrent decline of the developed countries and the rise of China changing the power structure of the international system. Recent events have thrust China, still in the process of developing its economy, into the spotlight as a superpower.

While few are likely to contest that China is on the rise, the question of whether or not it is already a fully-fledged superpower today is a fair question. In my view, China is indeed a superpower on the rise, with vast amounts of still untapped potential for further growth, but it is not quite there yet. However, China reaching its full potential is far from guaranteed. Despite its undeniable scale and resources, important economic, institutional, social, and diplomatic issues need to be dealt with, and the country still needs time to deal with its transition from a developing country to a real superpower.

Over the past three decades China's growth has been a wonder to behold. Since economic reforms in 1978 it has experienced unprecedented growth. Over the past 32 years the annual growth rate has averaged 10.02 percent. At the end of last year nominal GDP was about 23 times its value in 1980. Additionally, China managed to maintain robust growth through the global financial crisis of 2007-09, while many economies suffered significant economic malaise if not outright recession. While high GDP is undeniable, GDP per capita is low, exports are high but low-value- added, foreign exchange reserves are high but with little diversity, the fiscal position is strong but welfare is weak, oil is consumed in high amounts and inefficiently, and the capital market is rising, with many initial public offerings.

It is tempting to look at recent GDP statistics and conclude that China became a superpower when it overtook Japan as the world's second-largest national economy in 2010. It is also easy to get immersed in the media coverage of China, and the growing trend of countries looking to China to be a savior, a scapegoat, or a combination of both, and assert that only a superpower would draw so much attention. That being said, on closer inspection, there are some areas that need improvement, and some shortcomings that are delaying China's coronation as a superpower.

Does the world see China as a superpower already? There is no doubt China has made huge strides over the past decade. From a G7 world where China was not even in the picture as a major player, it has moved into a G20 world since the financial crisis, and is gradually gaining importance in global economic governance. Now there is talk of a G2 world in which China and the US would be the two major states, even if China has maintained a modest silence on the complimentary promotion.

The EU's recent requests for Chinese help in the sovereign debt bailouts show the costs of being seen globally as a superpower. As a superpower, China would be expected to contribute more to global aid and security; arguably a difficult sell for a country that still ranks 99th in GDP per capita. Again this shows that China does not have the credentials to join the superpower club.

Nevertheless, assuming it continues to grow at an average of 7 percent a year and that the US grows at 2 percent a year over the coming years, together with potential 20-30 percent gains in the yuan, China will overtake the US by 2020 as the world's largest economy. Despite an aging population, China still accounts for just under one-fifth of the global population. If it can boost per capita productivity to a top-tier level it has the prerequisites required to become a superpower of the highest order.

China's success over the past 30 years can be put down to high production with rich resource inputs in a severely competitive market, helped along by institutional reforms.

Institutional reforms have played a vital role, and there have been three main events that have acted as catalysts for growth.

The first, and arguably the most important event in China's recent economic history, was Deng Xiaoping's initial reforms in 1978, de-collectivizing agriculture and allowing private businesses to take part in the economy; these reforms set the framework for the country's evolution into a market economy.

The second event was Deng's southern tour of 1992, in which he reasserted the importance of continuing economic reforms, and the Shanghai Pudong area was revitalized. The tour sparked a huge wave of entrepreneurship that sharply drove growth, and further encouraged foreign direct investment.

The third event was China's entry into the World Trade Organization in 2001, which greatly increased the country's potential for international trade. Joining the WTO opened up the world economy for China's exports, and allowed for more foreign investment into China. These three key events have left surging GDP growth in their wake.

Supported by a favorable framework, China's growth has been strongly propelled by large quantities of input factors, one of the main reasons that China has been dominating competition in low-value added manufacturing. The key inputs are labor and capital.

Rapid growth has been driven in large part by the large influx of labor from rural agricultural areas to urban manufacturing jobs. The migrant worker population has supplied factories with a steady supply of low-wage labor that has given the country an incredible competitive advantage. Additionally, significant fixed asset investment over the last 30 years has provided China with the requisite capital and infrastructure to utilize the pool of low-cost labor. A lot of foreign direct investment in the country provided not only additional physical capital but, more importantly, technology transfer and managerial know-how that has been felt throughout the economy. With a seemingly endless supply of low-wage labor, and the infrastructure to back it up, China quickly rose to become the world's largest manufacturer.

One of the other factors driving growth is the intense market competition. Before the reforms, all the businesses in China were State owned; as such, there was no open competition, and incentives to improve efficiency were limited. As the process of reform began and China's economy shifted toward more of a market economy, opportunities were afforded to private entrepreneurs that gave great incentives to maximize efficiency, and consequently the level of competition skyrocketed.

In 1980 State-owned enterprises dominated, but by 2010 non State-owned entities accounted for over half of China's GDP as well as most urban employment; this transition was one of the major factors that fueled growth over these 30 years.

What sets China apart from most other countries is the structure of its provinces. With a degree of autonomy, individual provinces often specialize in various economic sectors. Province specialization leads to comparative advantages, leading to stronger national growth overall. As each province is responsible for its own economic statistics, and records are made of each province's contribution to national growth, there is aggressive competition among the provinces. This has led to many being strongly pro-business and a concerted effort to attract investment.

It is clear that China is still on the rise. Despite difficult global macroeconomic conditions, it is widely expected to maintain growth rate of about 7 percent in the near future, even as developed countries flounder at levels near stagnation.

Whether China is ready or not, it is rising toward superpower status.

The author is chief economist at Haitong International Research. The views do not necessarily reflect those of China Daily.

(China Daily 04/06/2012 page8)

Relief reaches isolated village

Relief reaches isolated village

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Earth Day marked around the world

Earth Day marked around the world

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Chinese fleet drives out Japan's boats from Diaoyu

Health new priority for quake zone

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

Russia criticizes US reports on human rights

China, ROK criticize visits to shrine

Sino-US shared interests emphasized

China 'aims to share its dream with world'

Chinese president appoints 5 new ambassadors

US Weekly

|

|