Thirty years of kissing

Updated: 2012-05-04 08:45

By Ginger Huang (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

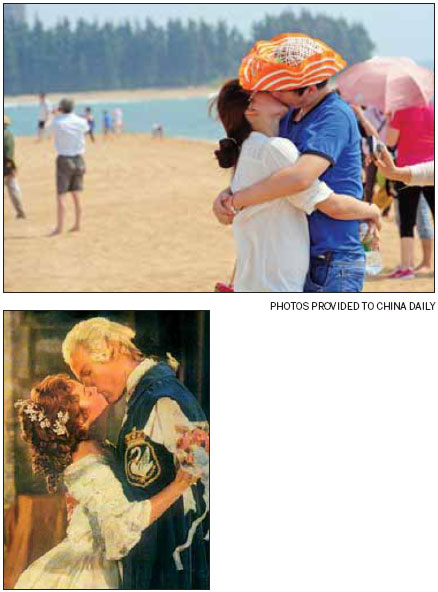

Above: A couple hug and kiss each other along the coast in Hainan province in spring. Left: A kissing scene published on the back cover of the magazine Popular Cinema ignited a national debate in 1979. Photos Provided to China Daily |

Plastic wrappers on the lips and riverside lanes - just some accessories for learning how to kiss again

多年的压抑,"接吻权"终于回归普通大众

In 1979, a national controversy broke out across China, about kissing. It started with a photo on the back cover of Popular Cinema, the only magazine with color pictures back then. It was a photo of a kiss scene from The Slipper and the Rose, an English film based on the story of Cinderella.

Soon, an angry letter landed on the editor's desk. Wen Yingjie, a clerk from the Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region, called the publication of the photo "decadent, capitalist, an act meant to poison our youths", and asked: "Are kissing and hugging the things most needed by our socialist China?"

"It's not that we don't want love," he said. "The point is what kind of love we want - pure, proletariat love, or corrupted, capitalist love?"

Wen further challenged the editors to face their crime and publish his letter. The editors complied and also invited readers to voice their opinions. In an age without the Internet, people wrote letters. In two months, more than 11,000 letters flooded the editors' office.

"The postman was exhausted. Everyday he had to carry in two sacks of letters," one of the editors recalled. Neither Wen nor the editors expected such a massive public debate.

After two months, the magazine announced the outcome of the debate. "Spring is not to be stopped by the cold," read the title of their conclusive article. It turned out that less than one-third of the incoming letters supported Wen. People wanted to see a handsome man and a beautiful woman kiss.

"We published it because it was a good-looking photo," the editor-in-chief said.

Considering the circumstances, Wen was not exactly being a prude about the photo. Long Feng, born in the 1960s, only saw kissing scenes in Eastern European films as a child.

"Why do foreigners kiss a lot?" He asked his father.

"Because they are foreigners," his father replied impatiently. "Only foreigners do that."

Of course, this was not true. People kissed in Chinese films as early as the 1930s; people kissed in classical literature.

In the 1960s, kissing and hugging were considered degenerate. People lived in fear of zuofeng wenti, literally "problems of lifestyle", but really it referred to illicit affairs. If someone was found to have a problem with his or her "lifestyle", that person would be humiliated, alienated by friends and criticized by his danwei (work unit). In a society with little mobility, a problematic lifestyle could completely ruin one's life.

It was very easy to be charged with zuofeng wenti. Being seen holding hands in public was just one way of eliciting the accusation. Any kind of closeness with the opposite sex could give rise to rumors.

In films, healthy, proletariat ways of expressing love included lending books to each other; giving fountain pens and notebooks as gifts; talking about revolutionary ideals instead of personal things when alone together. When critical moments came - when the characters needed to declare their love - it was customary for women to bury their faces in their palms and for men to scratch their heads with dumbfounded modesty.

"It was a sexless society," Pan Suiming, a sociologist, says of Chinese society then.

After steering clear from "unhealthy" ways for 30 years, the public became obsessively drawn to anything amorous. The Tremor of Life was a film shown in 1979. It was an honest representation of the purging that happened in those years. It had two beautiful, melancholic leads and good music. It was meant to help people cope with trauma.

But the biggest drive for its audience was not healing, but a kiss. The Tremor of Life was the first film to try to show a kissing scene after 1949. Before it was shown, incredible rumors circulated that the actors had put plastic wrapping on their lips before kissing.

In a full house, when the moment of kissing came, the audience was so quiet that they could hear water running through the theater's heater. All eyes were trained on the screen trying to identify the plastic wrapping. Just as people were holding their breath, the mother-in-law broke in with a bang and the lovers parted. The whole theater sighed in disappointment.

It seemed hard to break the long taboo of kissing. It was even harder for people to take a kiss as just a kiss.

Young people remained discreet in the early 1980s. Although being seen together was no longer considered "hooliganism", couples barely held hands and they could only kiss in certain locations, such as in bushes where no one else could see, or in areas commonly considered kissing spots, like on park chairs or along riverside lanes.

"We were like underground agents," Xiao Yu, a middle-aged man recalled of his dating experience. "When we went to the movies we walked apart as if we didn't know each other."

The first film that taught young people about kissing was Romance on Lushan Mountain. Judging by current standards, Romance on Lushan Mountain was a weird film. It was a boring love story with little drama and bland conversation. When it was time for the characters to say "I love you", they said "I love my Motherland; I love the morning of my Motherland" (in English) instead. There was a kiss, but it was just a quick, flighty kiss on the cheek. Young people nowadays laugh out loud when they watch it.

In 1980, however, the audience was different. They saw nothing wrong. The lead actor and actress had never tanlian'ai (been in a romantic relationship) themselves; neither had the majority of the audience. Because few people said "I love you" to each other in real life, few found it odd that the lovers shouted "I love my Motherland." They were just excited that here was finally a film not about revolution or class struggle, just about a relationship. It was the most watched film for several years in a row.

The Lushan kissing scene was shot on the top of a lonely hill. Yellow lines demarcated the set two miles away from the action. No one was allowed to stand by to watch except the director and the cinematographers. Still, these precautions did not help a girl's nerves.

"I was so nervous I couldn't find his lips," Zhang Yu, the lead actress, confessed 30 years later. "I meant to kiss him on the lips."

Although she missed, the kiss was legendary. The lovers chased each other in the woods and talked on a lawn. Young people left the cinema and imitated the characters.

In the 1990s, lifestyles were rapidly changing. People embraced rock 'n' roll, supermarkets, fast food, Hollywood films and an open attitude toward sex as modern ways to behave. China's first sex shop opened in 1993. A group of young women writers started to write openly about their intimate physical experiences. Fashion magazines introduced sex columns.

Kissing was no longer an issue - it hardly drew attention, in films or in reality.

That is, unless it is forbidden. In 2003, Shenzhen University laid down a new rule that students were not allowed to "hold hands, hug or kiss" on campus and quickly became the target of satire.

Xinhuanet published opinion pieces crying for "the right of kissing on campus" and questioning the legality of such rules. Sina.com commented in its social column, "If you feel uncomfortable seeing people kissing or hugging, that is your problem."

Courtesy of The World of Chinese, www.theworldofchinese.com

The World of Chinese

(China Daily 05/04/2012 page19)

Relief reaches isolated village

Relief reaches isolated village

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Earth Day marked around the world

Earth Day marked around the world

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Chinese fleet drives out Japan's boats from Diaoyu

Health new priority for quake zone

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

Russia criticizes US reports on human rights

China, ROK criticize visits to shrine

Sino-US shared interests emphasized

China 'aims to share its dream with world'

Chinese president appoints 5 new ambassadors

US Weekly

|

|