Asia's thought leader

Updated: 2012-07-20 08:01

By Thusitha De Silva (China Daily)

|

|||||||||

|

Kishore Mahbubani says social media is a new force that should be handled with care. Provided to China Daily |

Mahbubani argues that westerners' domination of global intellectual discourse is unhealthy

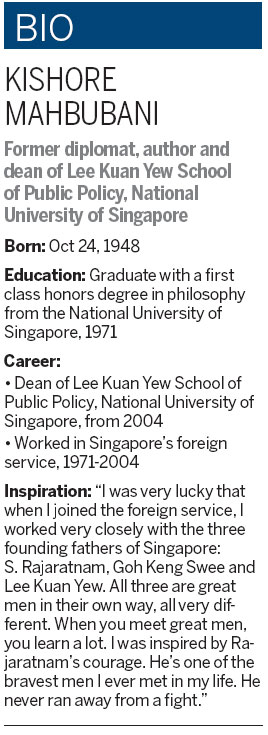

In November, Kishore Mahbubani was named one of the Top 100 Global Thinkers in 2011 by Foreign Policy magazine. It was the third time he made the list, having also done so in 2005 and 2010.

"The first time may have been a fluke, but making the list for the second and third time makes me think my ideas may be having an impact," says Mahbubani, who was appointed dean of the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy in Singapore in 2004 after a distinguished career spanning more than 30 years in Singapore's foreign service.

Described by the magazine as "the muse of the Asian century", Mahbubani is well-known in global intellectual circles as someone who consistently writes about, and articulates the rise of Asia. Publicly championing the idea of Asia's rise for the last 20 years, he calls this age "the return of Asia".

As he explains it, prior to the Industrial Revolution 200 years ago, the two largest economies in the world were China and India.

"It's only in the last 200 years that Europe and North America took off," he remarks. "But the last 200 years in the world's history has been a major historical aberration. And all historical aberrations come to a natural end."

In 1992, he wrote an article, The West and the Rest, for The National Interest, an American bi-monthly international affairs magazine. At that time, he was on a one-year sabbatical from the Singapore Foreign Service and a fellow at the Center for International Affairs at Harvard University. The article drew mixed responses in his immediate vicinity.

"Some Harvard professors received it well but some reacted very negatively," Mahbubani says.

Still, that article marked his initial thrust into the rarefied world of intellectual discourse. He notes that such discourse continues to be dominated by Western intellectuals, and ideas originating from Asian sources tend to be brushed aside.

"Most of the global intellectual discourse is among Western intellectuals. Americans like to quote Americans. What they don't realize is that Americans cannot understand what is happening in Asia. They should listen to Asian voices," he explains with the passion of someone determined to change the status quo.

"I have been trying to break down these walls of resistance, both in Europe and America, but there is an incredible amount of intellectual arrogance there. I'm telling them, 'Excuse me, stop being so arrogant and start listening to other voices'."

His next book, The Great Convergence: Asia, the West, and the Logic of One World, delves more deeply into this area: "I believe the current Western domination of global intellectual discourse is unhealthy. Westerners, who constitute only 12 percent of the world's population, must learn to understand the views of the 88 percent who live outside the West. My passion is to try to express the view of 88 percent of the world's population. That's my goal."

Born in Singapore to Pakistani migrants on the day the United Nations was chartered - October 24, 1948 - Mahbubani served as Singapore's ambassador to Cambodia from 1973 to 1974 during the war, as well as in Malaysia and in Washington.

Permanent secretary in the foreign ministry from 1993 to 1998, he was appointed Singapore's ambassador to the UN and served as UN Security Council president in January 2001 and May 2002.

"I was born on United Nations Day. That's how I became ambassador to the UN twice. As the Hindus would say, I was fated to become ambassador to the UN," he quips.

One of the big challenges that Asian leaders face today centers around the demands of a new, growing middle class in Asia, he notes. Recent history in East Asia and Southeast Asia shows that the early generation of leaders in Asia were very strong men. They included the likes of Park Chung-hee in South Korea, Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping in China, Suharto in Indonesia, Lee Kuan Yew in Singapore and Mahathir Mohamad in Malaysia.

"In those times, societies were able to handle such strong leaders because they were relatively poor and undeveloped. Civil society was weak and the number of educated citizens was small," he says.

But when countries succeed in developing a middle class, people immediately expect to play a bigger role politically and in terms of how their society should be organized: "So, I think the challenge for all Southeast Asian countries is how you engage this new middle class, give them a bigger role in the management of the country and yet keep the country strong and stable. That's a different challenge."

"You can have a strong leader," Mahbubani says. "But you need to have a strong leader who can win over popular support. You can't have the kind of top-down leadership you had in the past."

Mahbubani believes that as the middle class grows in Asia, it is natural that countries will develop new markets and economic growth will come internally. He cites research by a former World Bank economist, Homi J Kharas, who predicts that the middle class in Asia is set to grow to 1.75 billion by 2020 from about 500 million currently.

"Now if you're looking for growth markets, they are not in America and they are not in Europe. They are in our region. The fact that Europe and the US are slowing down will slow down the growth a little bit, but the internal demand will pick up. The shift of power to Asia is unstoppable. Asians have a hard time believing it," he says.

Another challenge he foresees facing leaders is the growing pervasiveness and influence of the social media. He describes it as a new force that is emerging and one that "we are still trying to figure out".

He notes that social media had a lot to do with the exit of Zine El Abidine Ben Ali in Tunisia and Hosni Mubarak in Egypt. But there is more to the story.

"The people who were leading the social media revolution in Egypt were the young, liberal, Western-educated people. But after they got rid of Mubarak, when the elections were held, none of the young, liberal, Western-educated Egyptians won. The elections were won by the Muslim Brotherhood. So social media can have some impact but it cannot change the fundamental nature of human society," says Mahbubani, who has his own website and Facebook account, though he is not on Twitter yet.

He also cites the example of social media in China, noting that some of the "most rabid criticisms of America" come from the social media rather than the official media in that country: "Social media doesn't necessarily always mean that you get rational voices surfacing. You can also have prejudices surfacing. So you have to be careful with social media, it's a new force that you have to handle with care."

China Daily

(China Daily 07/20/2012 page24)

Relief reaches isolated village

Relief reaches isolated village

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Earth Day marked around the world

Earth Day marked around the world

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Chinese fleet drives out Japan's boats from Diaoyu

Health new priority for quake zone

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

Russia criticizes US reports on human rights

China, ROK criticize visits to shrine

Sino-US shared interests emphasized

China 'aims to share its dream with world'

Chinese president appoints 5 new ambassadors

US Weekly

|

|