Pictures from the wood

Updated: 2012-07-27 07:34

By Ji Xiang (China Daily)

|

||||||||

|

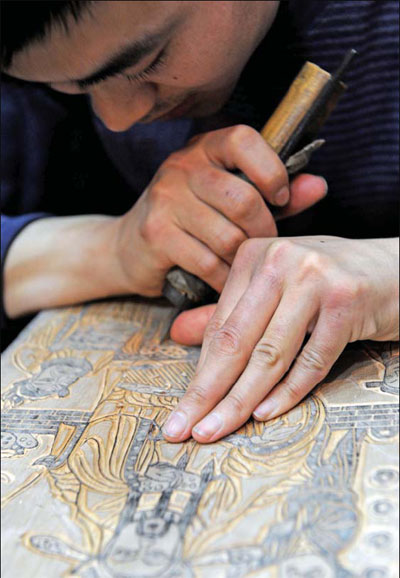

Carving is believed to be the most difficult step of the woodblock printing process. Photos provided to China Daily |

Artwork from major chinese invention continues to be chip off the old block

While the West's great museums run major exhibitions of this art form for hundreds of thousands to appreciate, in China it can also manifest itself in a village devastated by an earthquake or in the creations of student fashion designers.

It is especially noticeable at Spring Festival in January or February, when presented as New Year pictures, much in the same way as Christmas or other greetings cards.

|

Chinese families used to post nianhua during the Lunar New Year to bring good fortune and ward off evil. |

Woodblock printing, along with another of China's four recognized great inventions, papermaking, brought the world its first known books more than 1,300 years ago. (The other two credited inventions are gunpowder and the compass.)

It started as a way of spreading the Buddhist faith and was centered initially in the northwest corner of China on the Silk Road, where thousands of printed and illustrated texts were printed and stored. Since then, the craft has run off in a multitude of directions and variety of functional and artistic forms.

Currently, the Metropolitan Museum in New York is holding an exhibition of 130 Chinese prints that are "extraordinary in their stylistic diversity and technical ingenuity" displaying the different styles and development of the art through the ages. The prints are actually a part of the British Museum's collection, one of the most comprehensive outside Asia, and were originally exhibited in London in 2010.

Meanwhile, in Shanghai this year, gifts and souvenirs once kept by Soong Ching Ling, wife of Sun Yat-sen, the leader of the 1911 Revolution in China, went on display for the first time. Notable among the items was a woodblock print titled Five Heroes in the Langya Mountain.

It depicts the story of five Chinese soldiers in the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression (1937-45) who jumped to their deaths from a cliff rather than surrender.

The first lady gave the print as a gift to an American artist friend, who later based a comic strip on the heroic exploits of the war.

The early 20th century saw a major revival in black and white woodcuts following the collapse of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), and there were similar developments in Japan and Europe, as well as in the United States. In Shanghai in the 1920s, there was a booming poster industry.

But the height of woodblock print popularity took place 300 years earlier around the beginning of what would be the last dynasty. The craft may have emerged out of the peasantry, but it was bought up by affluent urbanites as a "silent language", a way of expressing nationalistic sentiments.

The "popular print" was a mass-produced colored picture, usually portraying a figure from folk religion, and most commonly used during the Lunar New Year. The nianhua (New Year picture) was posted by households to bring good fortune and ward off evil. The tradition survives today, but like Christmas cards, they are also given to express various sentiments in a variety of scenes and subjects.

The local fire department, for example, will deploy a suitably stirring print to inspire its brigade and public confidence in them, and carry instructions to homeowners on fire prevention and what to do in an emergency.

In Mianzhu in southwestern Sichuan province, a noted center of the craft, the popular prints have been used for similar effect following the horrendous earthquake which hit the area in 2008. On the white walls of rebuilt villages in Mianzhu are painted murals in the bold and bright styles of the local woodblock prints.

The workshops that churned out the prints hundreds of years ago and developed their own distinctive styles are still in existence in other parts of China. There are two leading place names in woodblock printing - Yangliuqing (green pillars and willows) in Tianjin in North China, and Taohuawu (peach dock) in Suzhou in the south, also known as "Southern Peach and Northern Willow".

Ling Junwu, a former researcher at the China Central Academy of Fine Arts who now runs Taohuawu New Year Pictures Museum, stresses the distinctive characteristics of different types of Chinese woodblock printing.

The Taohuawu style, he says, absorbed urban culture when it started, rather than the rural one and is more subtle in coloration. It is also more influenced by other art works, such as those of the Ming Dynasty painter scholar, poet and painter Tang Bohu (1470-1523).

However, Chinese woodblock printing also influenced artists from other countries and cultures, to the point where they became better known and more prized - Japan's ukiyo-e genre being the most recognizable, Ling adds.

"People know about ukiyo-e but they are astonished to see that China has her own versions of the fine art using similar techniques," Ling says. "A Russian expert said to me that Chinese woodblock printing was visually coherent with pure Chinese culture as a whole, including architecture."

Yangliuqing in the north, on the other hand, is renowned for its tradition of providing New Year prints to the imperial families of the past, and could be said to be more precise and detailed in execution. Nevertheless, it began in the early 17th century as popular art with workshops producing more than a million single-sheet prints a year.

Wang Wenda, 68, a master of Yangliuqing woodblock printing, typifies how the craft became high art.

"The most difficult step of the printing is the carving," he said at a recent fair in the village. "This is a technique that cannot be done by machines. To master such a skill requires at least 30 years of experience."

Contact the writer at jixiang@chinadaily.com.cn

Relief reaches isolated village

Relief reaches isolated village

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Rainfall poses new threats to quake-hit region

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Funerals begin for Boston bombing victims

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Quake takeaway from China's Air Force

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Obama celebrates young inventors at science fair

Earth Day marked around the world

Earth Day marked around the world

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Volunteer team helping students find sense of normalcy

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Ethnic groups quick to join rescue efforts

Most Viewed

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|

Today's Top News

Chinese fleet drives out Japan's boats from Diaoyu

Health new priority for quake zone

Inspired by Guan, more Chinese pick up golf

Russia criticizes US reports on human rights

China, ROK criticize visits to shrine

Sino-US shared interests emphasized

China 'aims to share its dream with world'

Chinese president appoints 5 new ambassadors

US Weekly

|

|